Scientist of the Day - Jean-Baptiste Biot

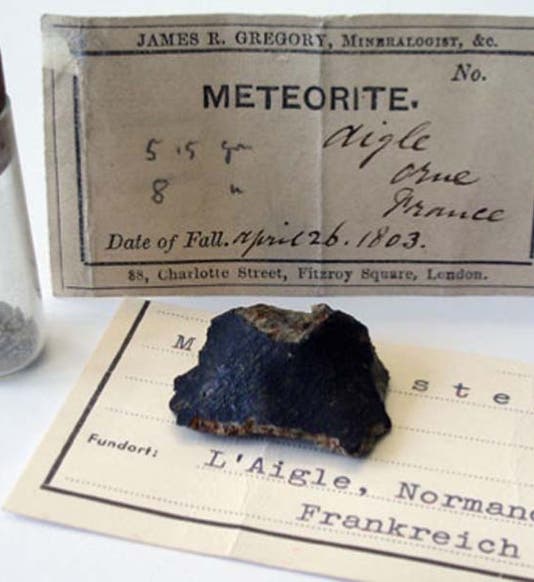

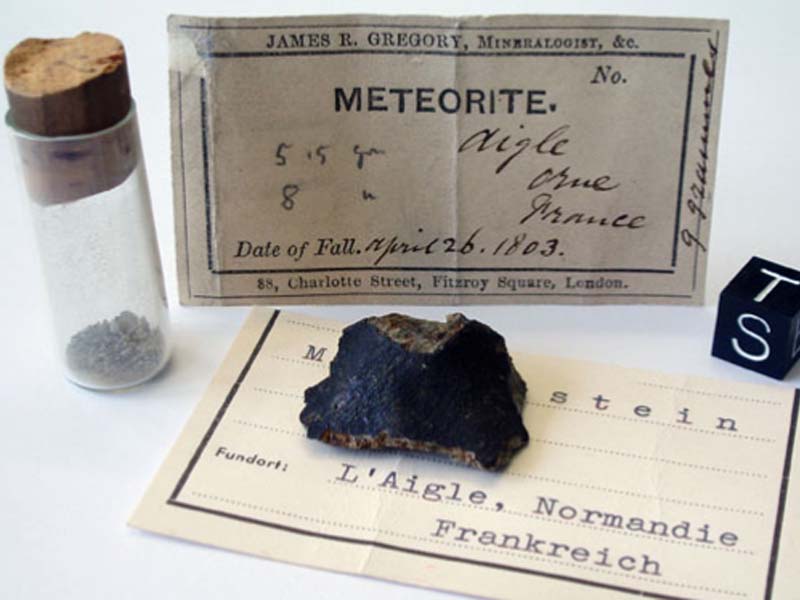

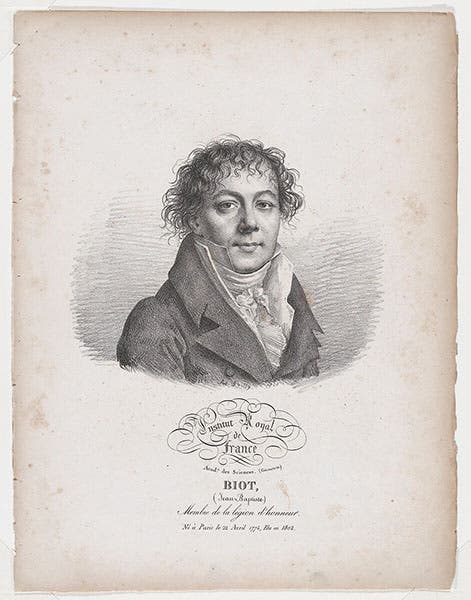

On Apr. 26, 1803, a shower of stones, accompanied by deafening explosions, rained down just north of the village of l’Aigle in the Orne department of Normandy in northwestern France. Word got out quickly, as some of the stones were gathered by enterprising villagers and sold to eager collectors, and reports (and stones) soon reached the Institute of France, the successor to the Royal Academy of Science in Paris. It was decided to send a young physicist, Jean-Baptiste Biot, to l’Aigle to investigate.

Reports of falling or fallen stones were not all that unusual at the time, but since the reports usually came from peasants, they were often discounted. Ernst Chladni in 1794 had published a book in which he claimed that stones did indeed fall from the sky and had an extraterrestrial origin. But most geologists and astronomers preferred to believe that such stones originated either in the atmosphere, or in volcanic explosions elsewhere on earth.

The fall at l’Aigle turned out to be the experimentum crucis for meteoritics; before l’Aigle, hardly anyone ascribed an extraterrestrial origin to meteorites; after l’Aigle, nearly everyone did. Biot was largely responsible for this turn-around. And he was able to effect the volte-face because he wrote a report in which he described hundreds of interviews with country folk who had witnessed the event, examined hundreds of stones, compared them with the native rock, and ruled out every possible explanation except an extraterrestrial one.

We wrote a post on Biot some years ago, which had nice photos of two attractive l’Aigle meteorite fragments, which we will not repeat here (our first image is a new one), but in that post we did not discuss or show any examples of Biot’s publications, which after all were what effected the revolution, and we showed no maps, of either the general area or the area of fall. So a follow-up post seems called for.

Map of strewnfield of meteorite fall at l’Aigle, Apr. 26, 1803, hand-colored frontispiece to Relation d'un voyage fait dans le département de l'Orne, pour constater la réalité d'un météore observé ą l'Aigle le 6 floréal an 11, by Jean-Baptiste Biot, 1803, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

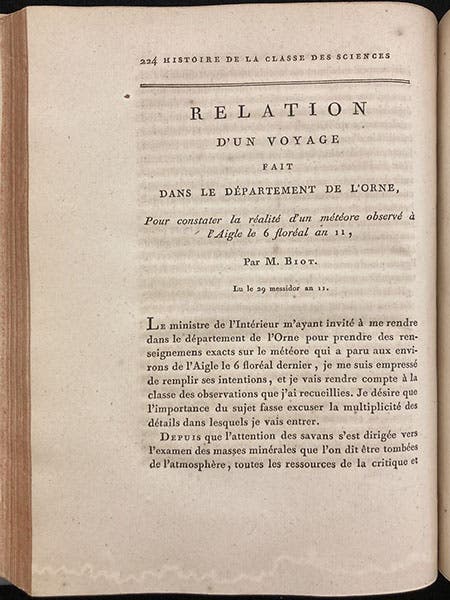

Upon his return, Biot immediately wrote up a report of his visit to l’Aigle, which he read to the Institute, and then published, with the title: Relation d'un voyage fait dans le département de l'Orne, pour constater la réalité d'un météore observé ą l'Aigle le 6 floréal an 11 (6 floreal an 11 is the date in the revolutionary calendar for Apr. 26, 1803). We do not own this 70-page pamphlet – I consulted the digital copy in the Bibliothèque nationale de France – and its most impressive feature is the frontispiece, which is a map of the area of fall near l’Aigle – what specialists in meteoritics now call a “strewnfield” (fourth image). It is in fact the first strewnfield map ever printed.

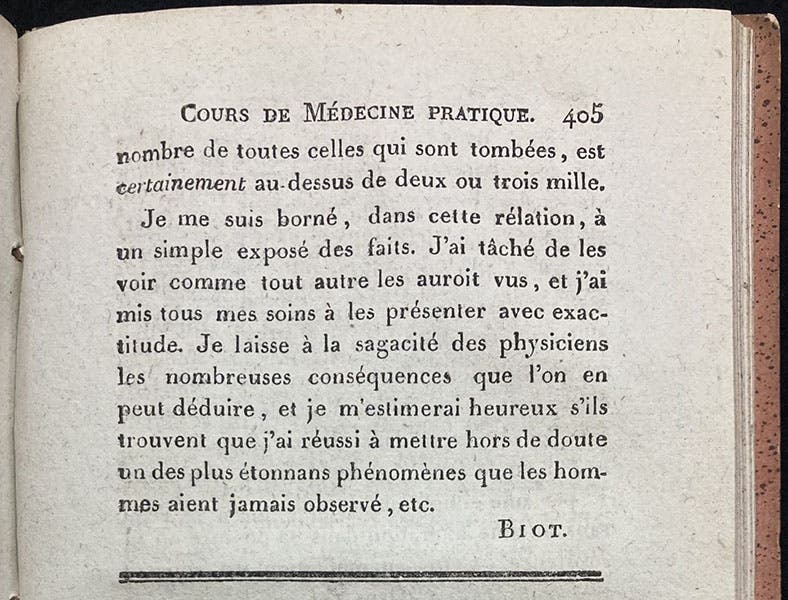

Biot then sent a shorter version of the same paper to Marc-Auguste Pictet, founder and editor of the Bibliothèque Britannique, a journal that attempted to keep French chemists abreast of what English chemists were doing. We have this journal, and we have Biot’s paper. I show the last page (fifth image), rather than the first, because it has Biot’s name, and because the last paragraph is often quoted. I will translate it in due course.

The Institute finally got around to publishing Biot’s original paper in its own Memoires, in volume 7, published in 1806. We have this as well, and we show you the first page, which has the full title (sixth image). The 1806 version, however, does not include the map of the strewnfield, which is most unfortunate

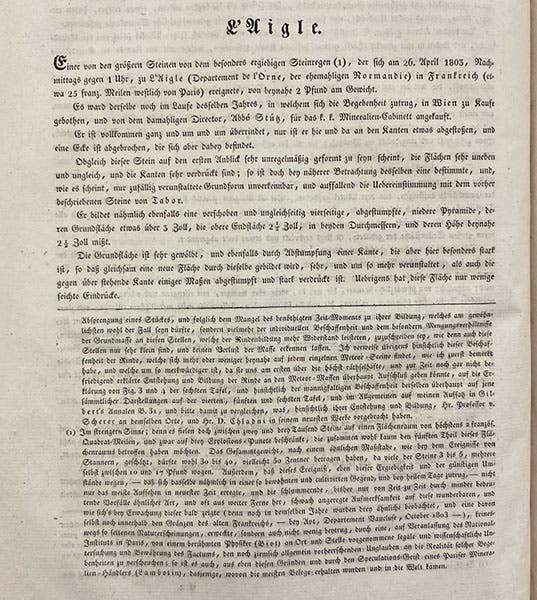

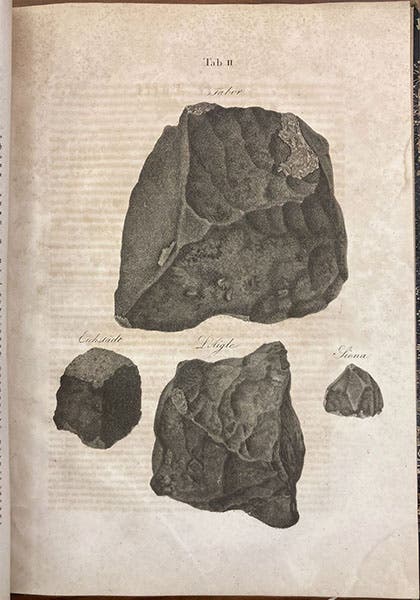

Finally, I show two pages from Karl von Schreibers’ Beytrage zur Geschichte und Kenntniss meteorischer Stein- und Metall-Massen (1820), because it does not seem to be generally known that Schreibers included a brief discussion of the l’Aigle fall – one of the first discussions outside France – and an illustration of a stone from the fall. (seventh and eighth images). The illustration is a lithograph – a new technique at the time – and we once wrote a post on Schreibers, in which we discussed his use of lithography, and showed other plates from his book. You can also see there another strewnfield map of 1808 in that post, which I thought at the time might be the first such map. I was wrong – Biot beat him to it.

One of the places Biot visited was the Château de Fontenil, a castle just north of l’Aigle and at the very bottom of the strewnfield (fourth image), which means the stones hit there first. Biot learned from the concierge that a large stone fell in the courtyard, and Biot was allowed to remove a small piece to take back with him. Out of curiosity, I tracked down the château – it is still there, and looks to be in remarkably good condition (ninth image). I could see no holes, intact or repaired, in the roof. But then, the concierge reported no direct hits to Biot.

As for the famous last paragraph of Biot’s Relation, here is a rough translation:

In this account, I have confined myself to a simple exposition of the facts; I have tried to view them as any other person would have seen them, and I have taken care to present them with exactitude. I leave it to the physicists to draw conclusions from them; and I shall consider myself a fortunate man if they find that I have succeeded in placing beyond all doubt one of the most astonishing phenomena that has ever been observed by man.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.