Scientist of the Day - Jean Baptiste d'Omalius d'Halloy

Jean Baptiste Julien d'Omalius d'Halloy, a Belgian geologist, was born Feb. 16, 1783, in Liège. He came from wealthy noble stock, but while furthering his education in Paris, he discovered geology, first in the Histoire naturelle of the Comte de Buffon, and then in the works of Georges Cuvier. He started to map much of northern France and Belgium on his trips back and forth. Around 1808, he received a commission, I do not from whom, to prepare a geological map of France, and he proceeded to work on that by travelling throughout France and into Germany as well. He apparently had his map finished by 1813, but his family persuaded him to turn to political pursuits, and he became governor of the province of Namur in 1815. But clearly, he kept his interest in geological mapping alive, because his map of France and adjacent territories was published as a folding plate in 1822 in the relatively new journal, Annales des Mines. We have a complete run of that journal in our Library.

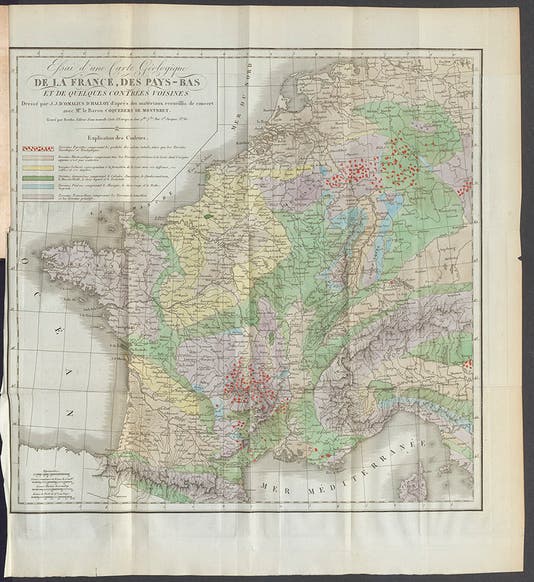

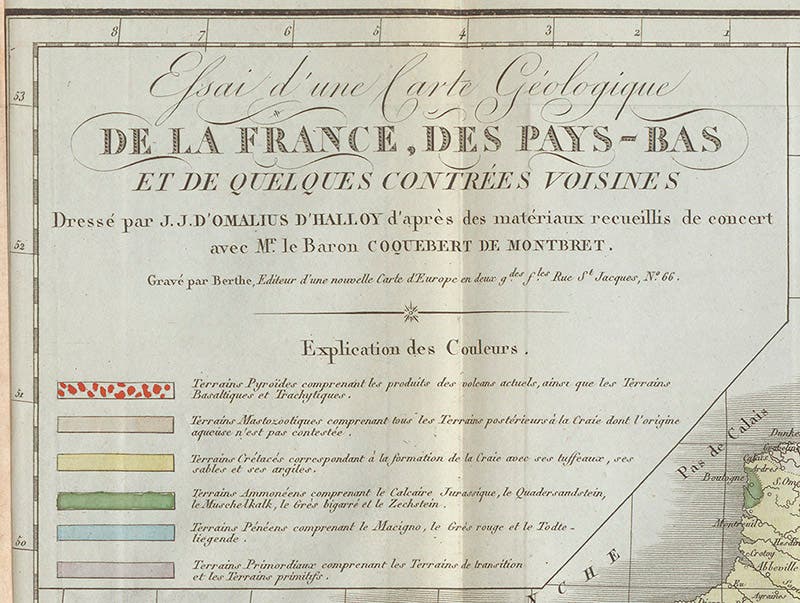

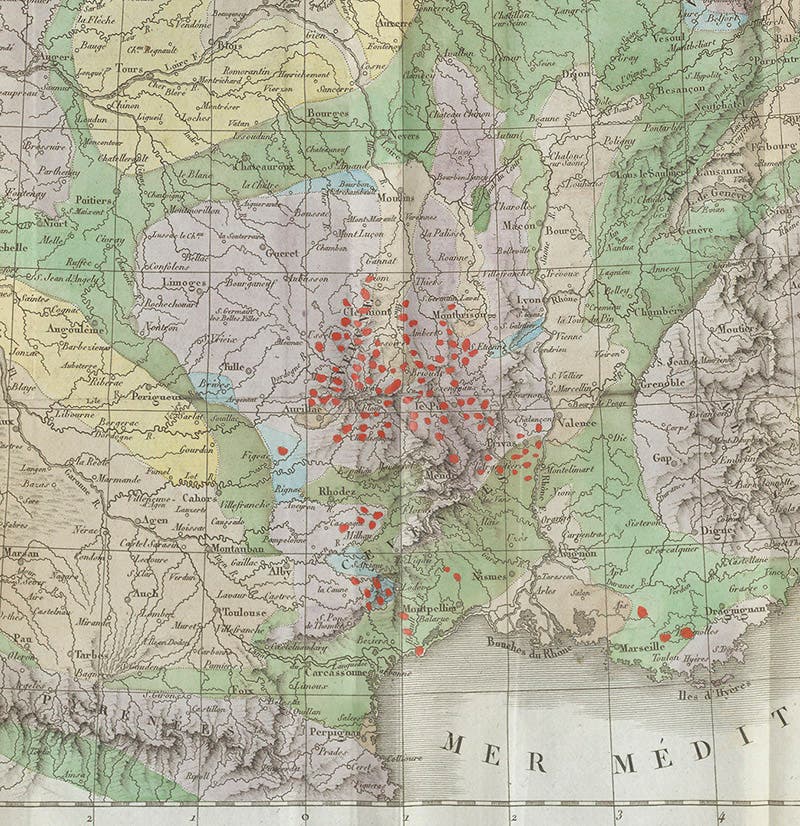

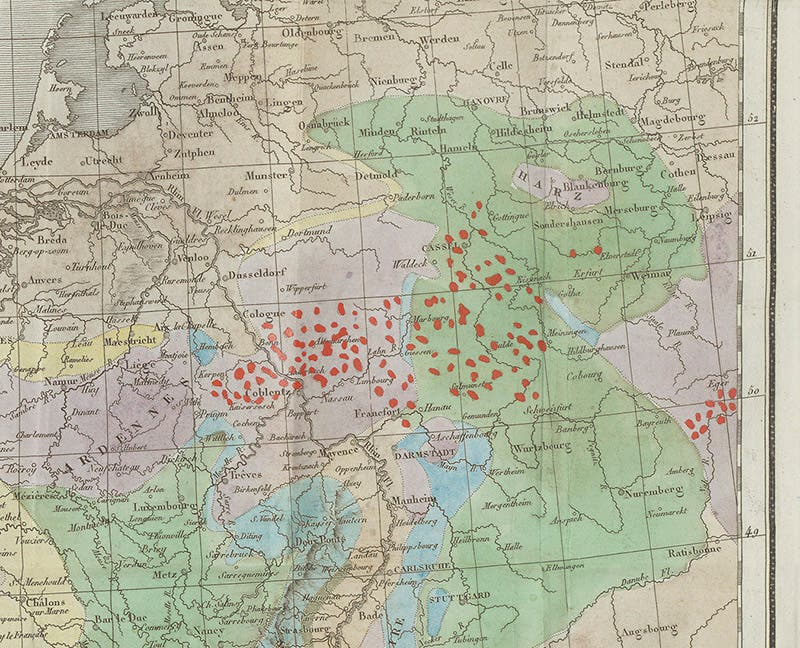

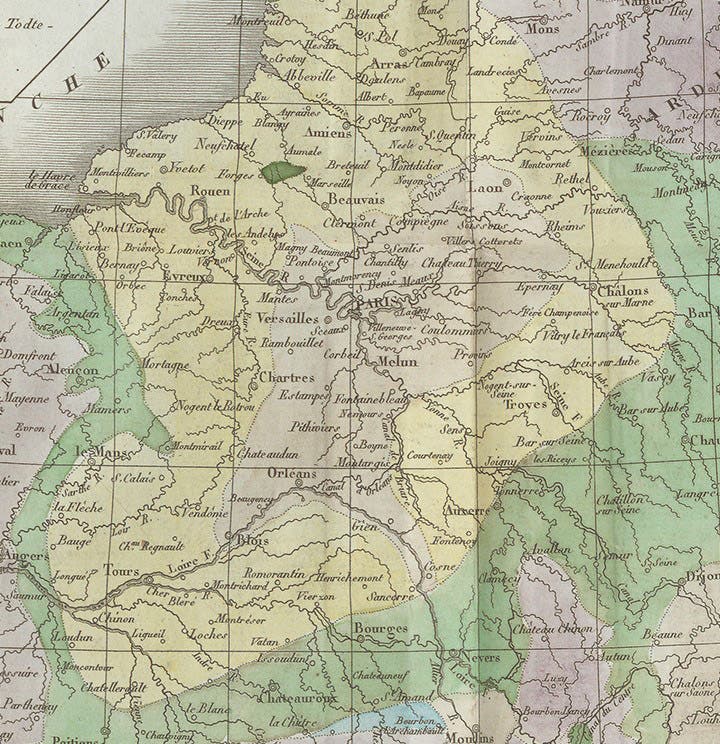

The map is a splendid thing (first image). It is not as impressive in size as William Smith's geological map of England of 1815, but it is rich in information. Central France, in the Auvergne region south of Clermont, has many extinct volcanoes, which no one recognized as such before Nicolas Desmarest in 1771. Consequently, the countryside is strewn and layered with volcanic rocks of all sorts, especially prismatic basalt. If we look at the key to the map of Omalius d'Halloy (second image), we see, on the first line, that he has indicated the presence of volcanic rocks, especially prismatic basalt, with rose-red dots, and if we now look at a detail of the Auvergne region, we can see those dots in copious use (third image). The region east of Cologne, just across the Rhine river, was also once volcanic, with an abundance of basalt columns and prisms, and Omalius d'Halloy has mapped these as well, as we see in another detail (image just below).

The region around Paris, what was then called the Paris Basin, is quite different, the rocks being geologically young and fossil rich; this is where Cuvier found most of his fossils (fifth image). Omalius d'Halloy called these "Terrains Mastozootiques" and indicated them with pink in the legend and on the map. Older yet are the “Terrains Crétacés,” or Cretaceous rocks, indicated on the map by yellow, and even older are the “Terrains Ammonéens,” colored green on the map, which correspond to what we would call Jurassic, Triassiac, and Permian rocks. You have to go quite a ways from Paris to find any rock that old. Omalius d’Halloy was one of the first to do that.

We displayed the entire Omalius d’Halloy map in our exhibition, Vulcan’s Forge and Fingal’s Cave: Volcanoes, Basalt, and the Discovery of Geological Time (2004). I do not know what effect Omalius d'Halloy's map had on later French geocartographers, such as Louis Léonce Élie de Beaumont, whose geological map of France (1840) rivaled that of William Smith in its detail (we have not yet profiled Élie de Beaumont in these posts, but we do own his 1840 map). But I do know that English geologists were impressed, because when Henry De la Beche published A Selection of Geological Memoirs Contained in the Annales des Mines (1836), a translation of the most significant geological articles to appear in that French journal in the past 20 years, his very first selection was a translation of Omalius d'Halloy's article of 1822, and De la Beche even had the map re-engraved and hand-colored, full-size and folded up, to include as the frontispiece to his book.

Omalius d'Halloy lived to the age of 91, spending most of his later years as a statesman and an official in various scientific societies. There is a statue with his likeness in Namur, the city he served so well (image above).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.