Scientist of the Day - Jean Perrin

Jean-Baptiste Perrin, a French physical chemist, died Apr. 17, 1942, at the age of 71. Perrin's youthful proficiency in math earned him entrance into the École Normale Supérieure in Paris in 1891, where he eventually completed his doctorate. Perrin showed an early commitment to what he called "atomistics," a belief in the physical reality of atoms and molecules, at a time when many chemists, such as Mendeleev, and many physicists, such as Ernst Mach, thought of atoms as convenient hypothetical constructs only. In 1901, Perrin even proposed a model of the atom that resembled a tiny solar system, with a positive charge in the position of the sun and with electrons moving around it like planets – this at a time long before it was known that the atom has a nucleus.

About 1903, Perrin became interested in colloids – tiny particles in suspension, which move randomly, exhibiting what was called Brownian motion. Brownian motion had been discovered by the English botanist Robert Brown in 1827, when he observed tiny pollen particles dart about when suspended in water (you can see Brown’s paper in our post on Brown). By 1900, it was suspected by some that Brownian motion was a result of the kinetic motion of the molecules making up the suspending liquid. Perrin would spend the next ten years trying to substantiate that hypothesis.

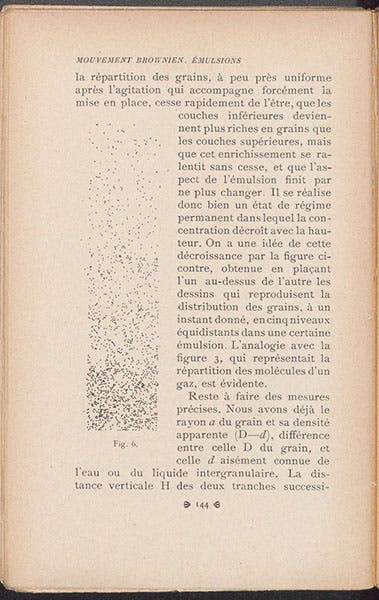

Perrin was greatly assisted in his quest by the invention in 1903 of a side-scanning microscope, the "ultramicroscope", which viewed colloidal particles by scattered light, rather than reflected light. With this instrument, Perrin could look at a layer of collloidal solution that was only microns thick, and count the particles and measure their motion, and then move up or down a layer and do it again. He was trying to determine if the density of the particles increased exponentially as one moved farther and farther from the surface, as the mathematics of kinetic theory predicted it should.

His experiments on Brownian motion resulted in four original papers in 1908. For these experiments, Perrin used a material called gamboge, which was a yellow pigment prepared from latex from trees in India and Southeast Asia. The preparation of gamboge particles, ensuring they were of a uniform size, was a very difficult task, one that Perrin mastered and hardly anyone else did. But the resulting experiments were successful, and seemed to verify the real existence of molecules and atoms. The Wikipedia article on "Gamboge," incidentally, fails to mention the pigment’s important role in colloid studies in the early 1900s and in demonstrating the substantial existence of atoms.

Perrin was not aware, when he undertook his famous 1908 experiments, that Albert Einstein had published an important paper on Brownian motion in 1905, the same year as his papers on special relativity and the photo-electric effect. Einstein's paper was entirely mathematical, with no basis in experiment, but it did derive Brownian motion from the kinetic energy of impacting molecules, and Perrin's results were consistent with Einstein’s calculations, so the two sets of papers supported each other.

The four papers of 1908 were later simplified and expanded into a book that could be read by non-specialists, called, simply enough, Les atomes, published in 1913. We have this book in our collections, in its original paper covers, and we show here the front cover (first image), which is, intentionally or not, more or less the color of raw gamboge, as well as an illustration from the book, which shows how the density of suspended particles increases with depth (third image).

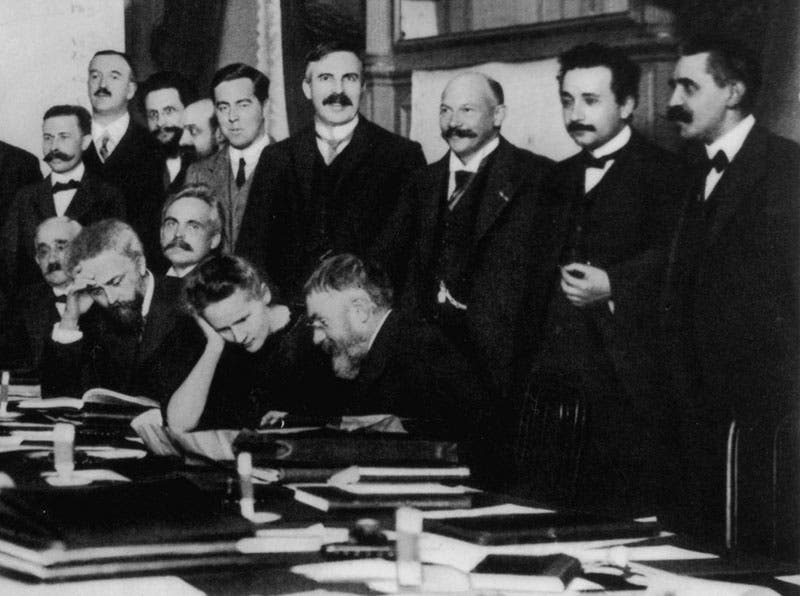

Perrin's work on Brownian motion, and his proof of the real existence of atoms, brought Perrin a chair in physical chemistry at the Sorbonne, which he held until 1940, and worldwide recognition as a gifted physical chemist, so that he was invited to attend the first Solvay Conference on Quantum Physics, held in Brussels in 1911. The official group photograph has Marie Curie and Henri Poincaré at the right end of the table, and next to them, head on his hand and reading a book, is Perrin. Albert Einstein can be spotted standing at the right. We show a detail of the photograph (fourth image), which puts Perrin at front left, still engrossed in his book.

For his work on colloidal suspensions and his affirmation of the existence of atoms, Perrin received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1926, which was the occasion for the portrait we show as our second image. He died in the United States, shortly after fleeing France during the German occupation, and his ashes were returned after the war for reburial in the Panthéon in Paris.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.