Scientist of the Day - Johann Dryander

Johann Dryander (born Johannes Eichmann), a German physician, anatomist, mathematician, and astronomer, was born in Hessen on June 27, 1500. He studied medicine in Germany and in Paris; in 1535, he became professor of medicine at the University of Marburg.

In 1543, Andreas Vesalius, a Flemish anatomist working in Padua, would publish his De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body, a watershed work if ever there was one, with scores of woodcuts, many full-page folios, on the anatomy of the human body, based on dissections done by Vesalius himself, and the illustrations made under Vealius’s direction by an artist. We own a copy of De fabrica, and have published a post on Vesalius.

But Vesalius's belief that anatomy books should be illustrated with images drawn from life and should include observations made by the author was not unprecedented. If we pass over Leonardo da Vinci, whose pioneering anatomical studies were unpublished and influenced no one in the 16th century, there were still other medical men who did dissections for their students, made new observations, and published them in books illustrated with woodcuts, just as Vesalius would do. We do not have any of these in our collections, since we do not collect works on human anatomy (two books by Vesalius and Bartolomeo Eustachi being the exceptions), so we have never featured any works by pre-Vesalian anatomists, as they are called, in this series. Today we begin to do so, looking at a wonderful book published by Dryander in 1537. For our illustrations, we rely on copies in the National Library of Medicine and the University of Michigan Libraries in Ann Arbor.

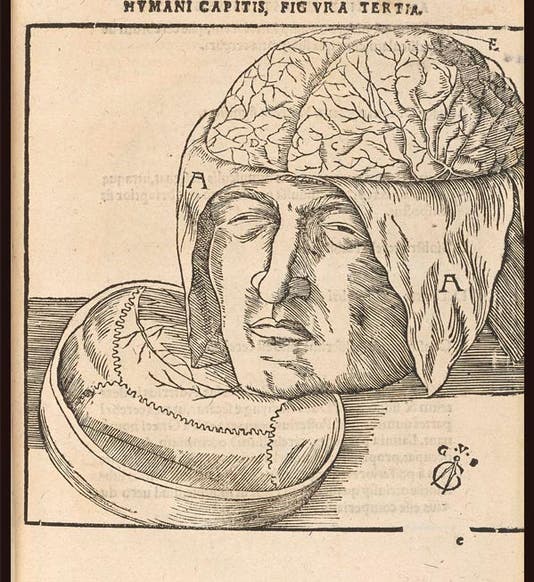

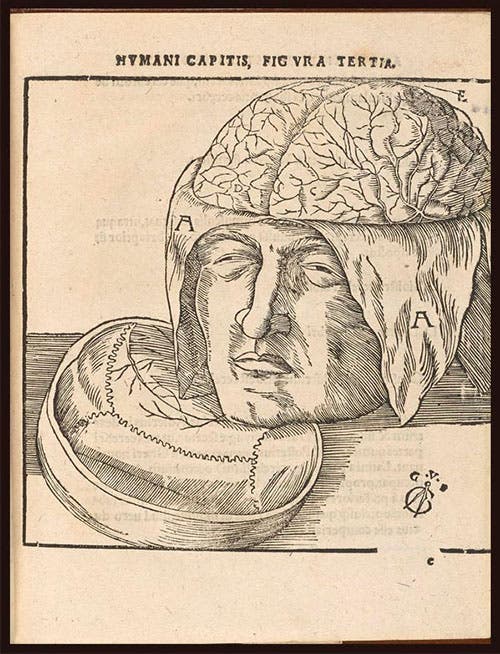

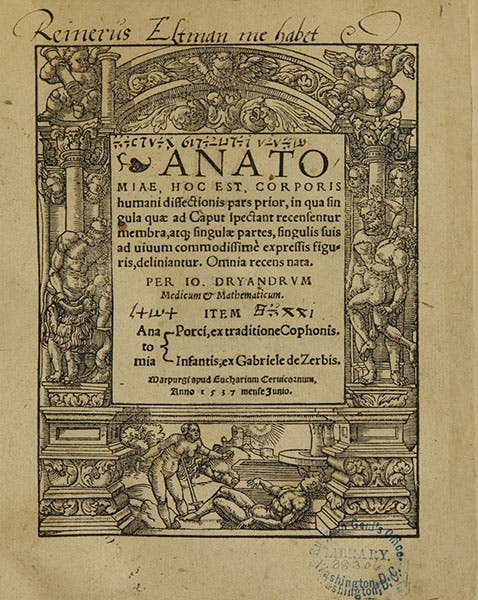

Dryander called his book Anatomiae, hoc est, corporis humani dissectionis pars prior (Anatomy, that is, Dissections of the Human Body, Part One), indicating that there was more to come, although the “more to come” was not forthcoming. Surprisingly, Dryander started with the head, not the thorax, and the first 11 woodcuts show a progression of stages as the skull was cut open and the membranes and then the brain were removed. This was something Vesalius would later do, with both the brain and the intestinal cavity, but Dryander did it first, and probably inspired the similar (if quite a bit more accurate and stylish) series in De fabrica six years later.

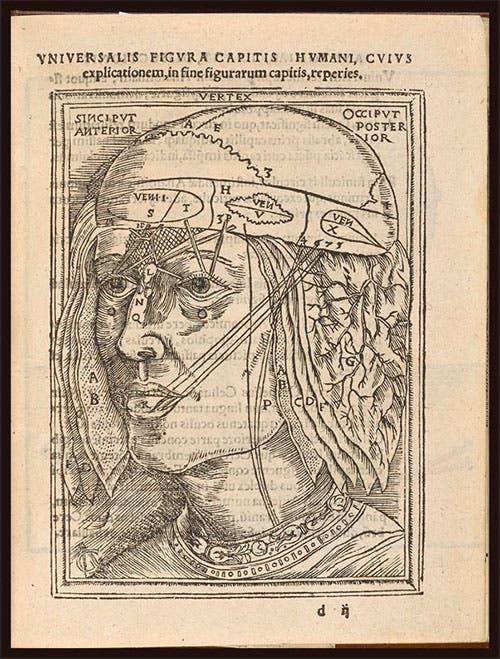

Dryander was not immune to his medieval precedents, and one of his woodcuts took a medieval woodcut of the ventricles of the brain (including the rete mirabile, the “marvelous network” behind the forehead that was a mistaken notion of the ancient physician Galen), and superimposed on it the layers of skin and membranes that protect the skull, peeled back to show the cranial sutures (fourth image).

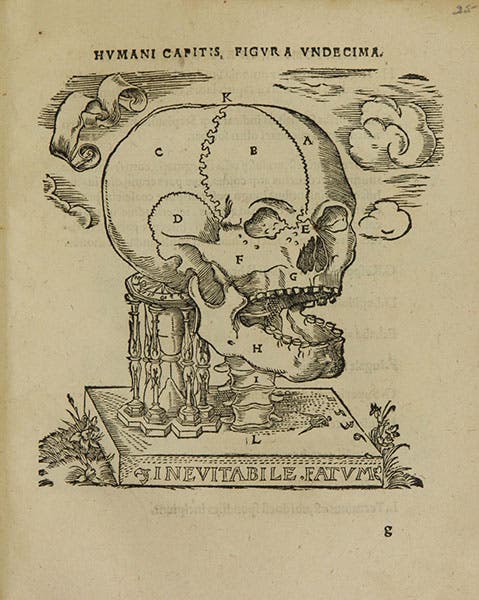

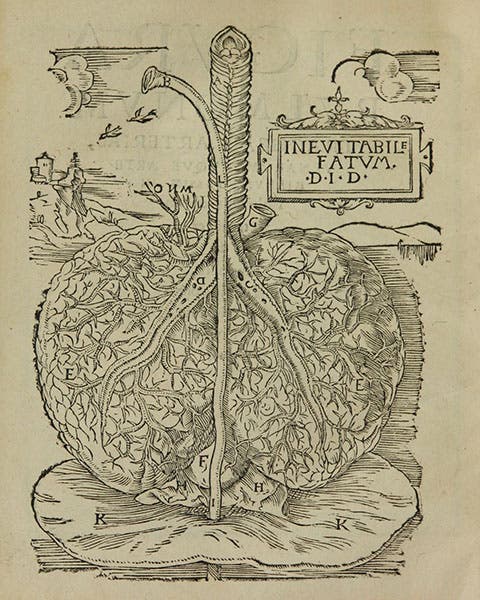

Tacked on at the end (but not part of the projected “Pars posteriori”) is a short treatise, De pulmo (On the lung), which has several more woodcuts, completely original, of a lung (sixth image) and a thorax, mounted like torsos in a delightful fashion, again foreshadowing similar conceits by Vesalius. The expression Inevitabile fatum appears on several of the woodcuts, and reminds us that inevitable fate will turn us soon enough into skulls and bones. The sand hourglass in the fifth image provides a further reminder.

It is surprising that Dryander did not finish part two of his anatomical textbook; he was only 37 when part one was published. Perhaps the appearance of Vesalius’s De fabrica in 1543 suggested that he seek other pursuits. He does seem to have turned to astronomy and mathematics after 1540, as he edited and published a second edition of Peter Apian’s 1524 book on cosmography, which Dryander called Cosmographiae introductio (1543). We have the second printing of 1544 in our collections. Dryander continued to occupy the chair of medicine at Marburg until his death in 1560.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.