Scientist of the Day - Johann Lambert

Johann Heinrich Lambert, a Swiss natural philosopher and mathematician, died Sep. 25, 1777, at the age of 49. Lambert is a curious historical figure; extremely accomplished, a worthy member of a select company that includes Leonard Euler and Immanuel Kant, except that hardly anyone has ever heard of Lambert, save the optician who measures the luminance of a light source in lamberts, or the cartographer who produces an aviation map using the Lambert conical projection, or the astrophysicist who measures the albedo of a moon of Saturn, using a term for reflectivity that was coined by Lambert. Lambert spent the last 13 years of his working life in Berlin, where he was appointed a member of the Academy of Sciences there. He wrote original works on pyrometry (the measure of heat), photometry (the measure of luminance), hygrometry (measurement of humidity), cartographic projections (he invented 7 new projections, several still in common use), even treatises on non-Euclidean geometry and irrational numbers.

But perhaps his most accessible work for the non-specialist is a book he published just before coming to Berlin: Cosmologische Briefe über die Einrichtung des Weltbaues (Cosmological Letters on the Arrangement of the World Structure, 1761). Here he speculated on the arrangement of stars in space and pondered an explanation of the band of stars that circles the night skies, which we call the Milky Way. Lambert concluded that the Milky Way is an enormous system of stars, shaped like a thin disk or ring, containing the Sun and millions of other suns, and he proposed that the small nebulae that were then being spotted in telescopes were other Milky Ways, but further away, containing just as many stars as ours. Thomas Wright had made a similar proposal in 1750, and Immanuel Kant in 1755, but Lambert didn't know about either man's work, and so his explanation of the Milky Way – a correct explanation, as we now know – was as original with him as it was with Wright and Kant. These three are the true fathers of galactic studies, and yet we too often celebrate only the twosome of Wright and Kant. Lambert deserves an equal share of the cosmological pie.

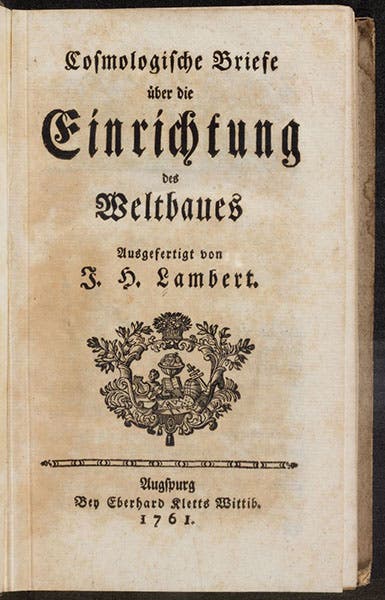

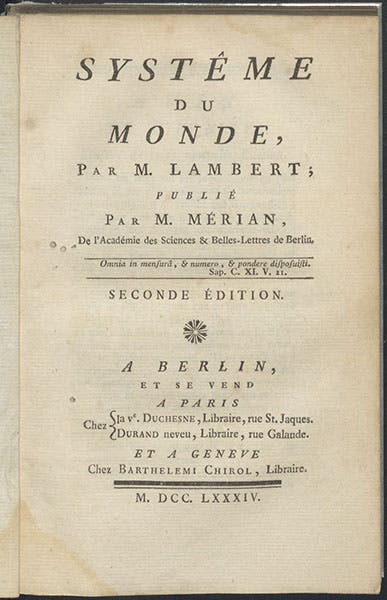

We have a copy of the first edition of his Cosmologische Briefe in the History of Science Collection at the Library, in a black-letter German font (first image), as well as a translation into French, which is in pristine condition and still in its original paper wrappers (second image). If you actually want to read the work rather than admire it, we also have a modern translation into English, published in 1976 (my personal copy still has the dust jacket, so we show that copy here, third image). None of these versions has any illustrations, which makes it difficult to find images for a post on Lambert, and the situation is not improved by the fact that it is hard to find a portrait of Lambert with a pedigree. The best I can do here is show you a poster for a 2017 Symposium honoring Lambert, held at the Friedrich Schiller-Universität in Jena (fourth image). The portrait reproduced on the poster would seem to be from a 19th-century book or broadside, which at least lends it a look of authenticity, even if bibliographic details are lacking.

In addition to the three versions of the Cosmological Letters, we also have a first edition of Lambert’s Pyrometrie (1779), a very early contribution to what will later be called thermodynamics. At the end are a series of graphs treating heat flow. Lambert was one of the very first scientists to arrange data in graphical form and allow the graphs to further the argument; his place in the history of graphic illustration might be a worthy subject for a future post.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.