Scientist of the Day - John Argentein

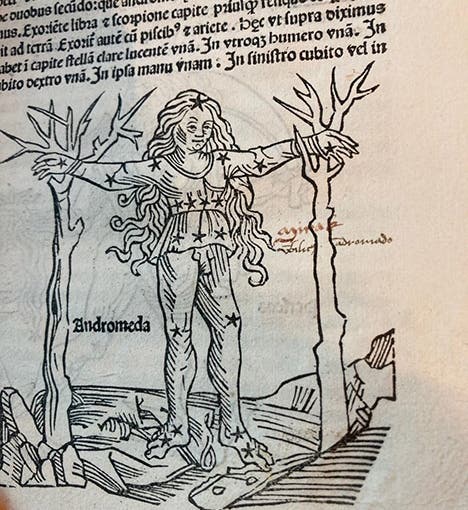

The constellation Andromeda, woodcut in John Argentein’s copy of Hyginus, Poeticon astronomicon, published by Erhard Ratdolt, 1482, now in Gloucester Cathedral Library (photo by Kathy Baldree)

John Argentein, an English physician and cleric, died Feb. 2, 1508, at an unknown age. His name is often spelled Argentine, but he usually signed his name "Argentein”, so we choose that form. Argentein is best known for his association with the "Princes in the Tower,” the two young sons of King Edward IV who, after Edward's death in 1483, were sequestered in the Tower of London by their uncle, the Duke of Gloucester. The princes mysteriously disappeared, paving the way for the Duke to become King Richard III. Argentein was the last person to see the two boys alive in the summer of 1483, and was quoted as saying that young Edward sought daily confession as he was in fear for his life. So Argentein's name regularly comes up when the fate of the princes (still undecided) is debated, but not much otherwise. He himself disappeared for three years after the princes vanished, and then he turned up in a variety of clerical positions, until he became Provost of King's College, Cambridge, in 1502, a post he held until his death.

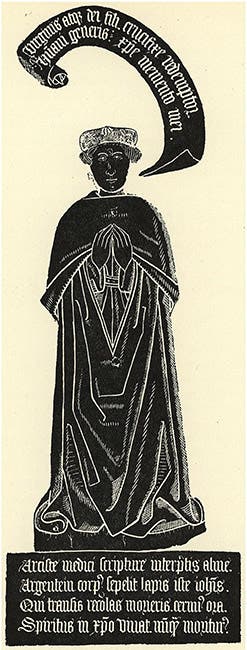

Portrait brass of John Argentein, King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, from the Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 1956 (jstor)

Argentein, however, had a personal library, and it is in this context that we discuss him today. Last fall, I received an inquiry from a researcher, Kathy Baldree, who has an avid interest in Argentein, and who had discovered that Argentein owned a sammelband of 6 books printed by Erhard Ratdolt of Venice, and that the books still survived in the Library of Gloucester Cathedral. One of the books in the sammelband (the name for a volume containing two or more books that were not published together but which have been bound up together) was the cosmographical work, De situ orbis, by Pomponius Mela, printed by Ratdolt in 1482.

A word about Ratdolt is in order. He was a German printer who moved to Venice in 1476 and set up shop. He was the first printer in the world to specialize in scientific books, printing the first edition of Euclid's Elements, complete with diagrams (1482); a beautiful edition of Sacrobosco's Sphere, with diagrams printed in two colors (1482), and multiple editions of the Calendarium of Regiomontanus, as well as two editions of Hyginus' Poeticon astronomicon, a book on the constellations (1482 and 1485); Ptolemy's book on astrology (1484), the medieval Alfonsine astronomical tables (1483); and the Pomponius Mela mentioned above (1482). We have nine works printed by Ratdolt in our collections, including all the one's just mentioned, and all in beautiful condition. I should have written a post on Ratdolt by now, but since we lack any dates for Ratdolt, he tends to slip through the sieve when we are looking for notable anniversaries.

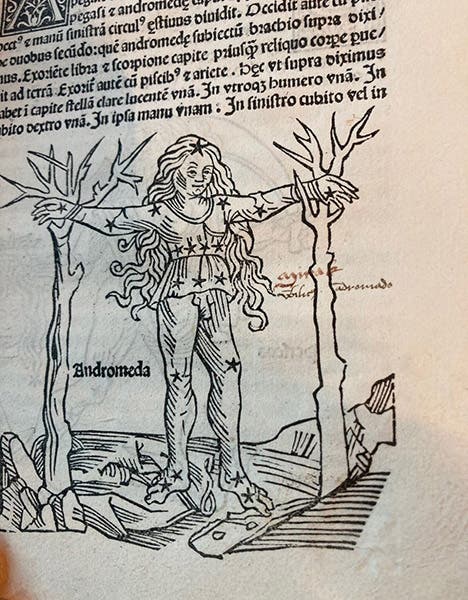

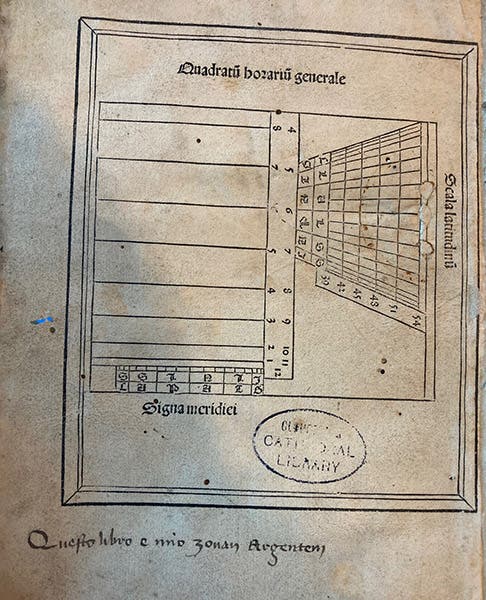

Last page of Calendarium, by Johannes Regiomontanus, published by Erhard Ratdolt, 1482, from the copy of John Argentein, with his signature, Gloucester Cathedral Library (photo by Kathy Baldree)

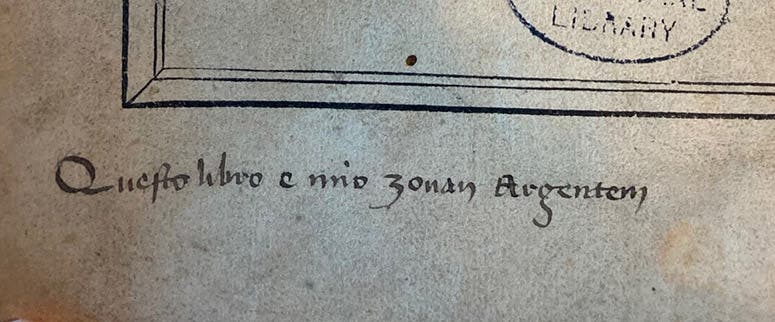

However, I did write a post on Pomponius Mela, where we began with the 1482 Ratdolt printing of De situ orbis, which is how Ms. Baldree found me. She wondered, since I apparently knew something about Ratdolt, if I could shed any light on Argentein's sammelband, which included a copy of Ratdolt's printing of Pomponius Mela. I told her that sammelbands were usually put together by the owner, not the printer or bookseller, and that Argentein was unlikely to have found all those books at a London bookstall. I don't think I shed much light otherwise, but Ms. Baldree figured it all out anyway. All six volumes (Mela, the Calendarium of Regiomontanus, the Poeticon of Hyginus, two astrological books by Alchabitius and Abraham Judaeus, and the Prognosticon of Hippocrates), had been printed by Ratdolt between 1482 and 1485. The Regiomontaus Calendarium (the 1482 edition) had been signed on the last page by Argentein: "Questo libro e mio zouan Argentein" (“this book is mine, John Argentein”). It is notable that the ownership inscription was written in Italian, not English, and that he used the peculiarly Venetian form for John: Zouan. It seems reasonable to conclude that Argentein was in Italy when he wrote that inscription, probably in Venice, and that he was there until at least Dec. 24, 1485, when the Abraham Judaeus book was published by Ratdolt. So the mystery of Argentein's whereabouts between the disappearance of the Princes in the Tower and 1486 might well now be solved, by a sammelband, a signature, and a clever California researcher.

Detail of third image, signature of John Argentein, in his hand: "Questo libro e mio zouan Argentein" (“this book is mine, John Argentein”) (photo by Kathy Baldree)

Ms. Baldree recently had the opportunity to view Argentein's six Ratdolt books in the Gloucester Cathedral Library. The sammelband was disbound some time ago, for reasons unknown, but the books are all in good condition, and the photos shown here of a Hyginus woodcut of Andromeda (first image), and the last page of the Regiomontanus with signature (third and fourth images), were taken by Ms Baldree last month and kindly offered to me for this post.

One might wonder, why did Argentein choose those six Ratdolt books when he was in Venice? Actually, the choices make great sense. It is thought that Argentein studied medicine at Padua in the 1470s, and we know that he saw the princes in his role as physician, and that he was later the physician for Arthur, Prince of Wales, son of King Henry VII. Since medicine in the 15th century was intimately associated with astrology, a learned physician would need calendars, and astrological treatises, and books about the stars. The only book that doesn’t obviously fit is the Pomponius Mela, but perhaps the information it provided on different climes would have been helpful to a physician. The only book missing was Ratdolt's edition of Ptolemy's Quadripartitum, a basic astrological text published by Ratdolt in 1484. Perhaps Argentein bought that as well, but it wouldn't fit into his sammelband, which must have already been a thick volume.

We hope Ms. Baldree writes up her work for publication, so this post becomes just a prelude to a more important work of scholarship. Meanwhile, if you want to pay homage to John Argentein, there is a terrific portrait in brass in the chapel of King’s College, Cambridge (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.