Scientist of the Day - John Fothergill

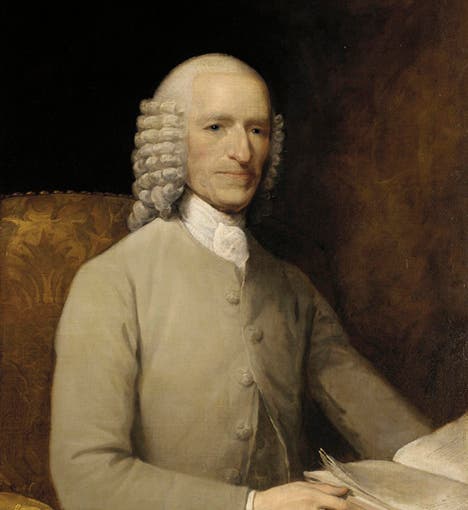

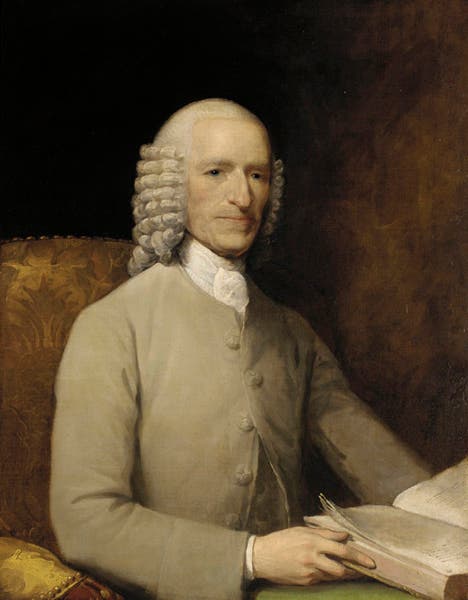

John Fothergill, an English physician, was born Mar. 8, 1712, in Yorkshire. Fothergill was a Quaker, one of a small but extremely influential Christian sect that had a great social impact in 18th-century England and its colonies. Fothergill studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and then moved to London, where he set up a general practice that grew quite lucrative. He also became interested in botany, or more accurately, gardening. He bought an estate named Upton House in West Ham, Essex (now in Newham in East London), where he established one of the largest private gardens in England, complete with greenhouses, which were a rarity at the time, due to the prohibitive tax on glass.

Partly to supply his garden with exotic plants, and partly just because Quakers did this kind of thing, Fothergill patronized botanists and plant collectors, especially Quaker botanists. He was the principal patron of Sydney Parkinson, himself a Quaker, who was the botanist on James Cook's first voyage to Australia and around the world, 1768-71, and who collected and drew an extraordinary numbrer of plants, most of them unknown to English gardeners. Unfortunately, Parkinson died of dysentery on the voyage, and his collections, drawings, and paintings went to his other patron, Joseph Banks, who hired Parkinson for the voyage and who himself went along.

A second individual who was the recipient of Fothergill’s generosity was Henry Smeathman. Fothergill and Banks (and Dru Drury, an insect collctor) sponsored Smeathman’s passageto Sierra Leone in West Africa in 1771 to collect rare insects (Drury espcially wanted a goliath beetle, which Smeathman supplied). I have not determined if Smeathman was a Quaker, but as one of his goals was to establish a colony without slaves, he might have been, since Quakers were universally opposed to slavery. Smeathman managed to discover and write about African termites and their mound-making capabilities, which was not on the agenda of Fothergill, Banks, and Drury, but turned out to be Smeathman's principal contribution to natural history, about which you can read more in our post on Smeathman.

But the best-known recipient of Fothergill's patronage was the American botanist William Bartram. William was the son of John Bartram, himself a naturalist, and a Quaker; William was a Quaker as well. John built a home and a garden in Kingsessing, just west of the center of Philadelphia, and proceeded to fill his garden with plants he found in journeys through colonial America. William went along when young, and then on his own, and continued to maintain the garden after John died in 1777. In 1766, William somehow picked up the patronage of Fothergill (John had Peter Collinson, another Quaker, as his patron until Collinson died in 1768). Bartram sent Fothergill seeds, and plants, and artworks that he drew himself, for over ten years; Fothergill kept the paintings in an album. When Fothergill died in 1780, Banks acquired the album, and eventually it ended up in the British Museum, where you may still find it. It is called the Fothergill Album. None of the images were printed until 1968, when the entire volume was issued in full-size facsimile (i,e., in folio), with abundant scholarly apparatus to help identify all the plants and animals depicted and the localities from which they came. Our copy, oddly, is kept in the rare book vault, where, however, it seems quite happy.

The most famous painting in the Fothergill Album depicts the Franklin tree, Franklinia alatamaha, named after Benjamin Franklin, which both John and William saw flowering in Georgia; it subsequently disappeared in the wild, to survive only in the Kingsessing garden in Philadelphia (second image). All modern Franklin trees are descendants of the ones grown at Kingsessing by the Bartrams. The painting, dated 1788, was actually sent to Robert Barclay after Fothergill had died, but it ended up being included in the Fothergill Album.

Sandhill crane, drawing by William Bartram, Fothergill Album, Natural History Museum, London (nhm.ac.uk)

We also show a drawing from the Fothergill Album that is not famous at all, although it is quite charming. It is a sketch of a sandhill crane, which Bartram observed in Florida (third image). The drawing is the only survivor of the encounter, since the bird it depicts was shot and eaten.

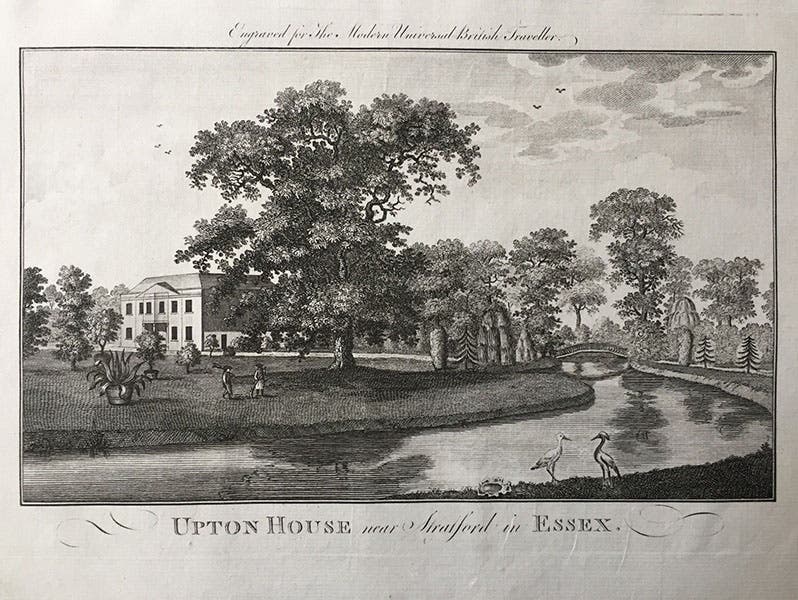

Fothergill's garden at Upton House was catalogued after his death by another Quaker friend, John Coakley Lettsom, and published as Hortus Uptonensis (1784?). This is a very scarce book; we do not have a copy in our collections.

If you search for images of Upton House and its gardens, you will find several, but most likely they will depict the Upton House where Joseph Lister was born, which is a different Upton House. However, I did find for sale on eBay a print from a 1779 book that depicts an Upton House in West Ham, and this is most likely the residence of Fothergill, although the famous gardens are not much in evidence (fourth image).

Finally, should you ask, as you well might, why were there so many prominent Quaker botanists and patrons of botany in the 18th century, my answer is, I have no idea. I understand why Quakers were fervent abolitionists, but not why they were so attracted to the world of plants and gardens. I am unaware of any plausible explanation offered by scholars, and if there have been suggestions, I would like to hear about them.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu