Scientist of the Day - John Mayow

John Mayow, an English chemist, physician, and physiologist, was born in 1642 in Cornwall. In the 1660s in London, he and a number of others, including Christopher Wren and Robert Boyle, were investigating the mysteries of respiration and combustion. No one at the time knew the function of respiration; some thought it cooled the heart, others that it served to connect the left and right sides of the heart. The London group was able to show, sometimes using Boyle’s recently invented air pump, that respiration, like combustion takes something out of the air. A flame burning in a confined space uses something up, and goes out; a mouse, placed in the same space, will also expire, indicating that air, or part of the air, is necessary for both life and combustion.

Mayow, for some reason, was not a member of the Royal Society of London, which provided the setting for the work of Wren and Boyle, so he pursued further work on his own. In 1674, Mayow published his Tractatus quinque, a collection of 5 treatises, one of which was titled “De sal-nitro, et spiritu nitro-aereo" and has become somewhat celebrated in the history of chemistry, although often for the wrong reasons. In the tract "On the salt nitre", Mayow argued that common air is a mixture of an inert mass and a small number of active particles, which he called a "nitro-aerial spirit." This spirit, Mayow maintained, is the part of the air that is essential for combustion and respiration. When it is used up, combustion ceases and living things die. He called it "aerial nitre" because ordinary nitre, or saltpeter, will burn without the presence of air, suggesting that saltpeter contains a fixed form of nitre that works in a similar fashion to the aerial kind.

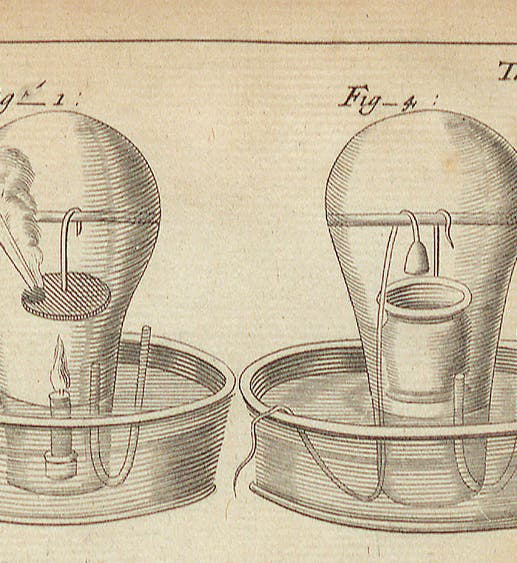

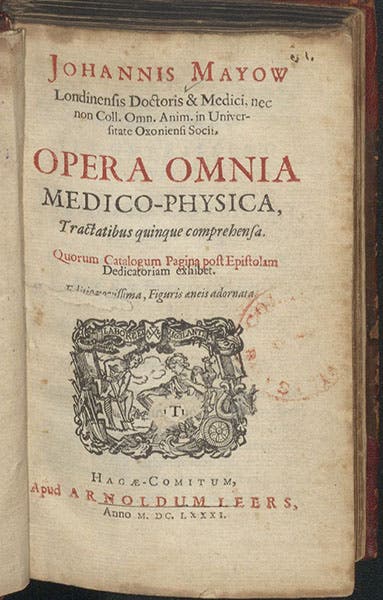

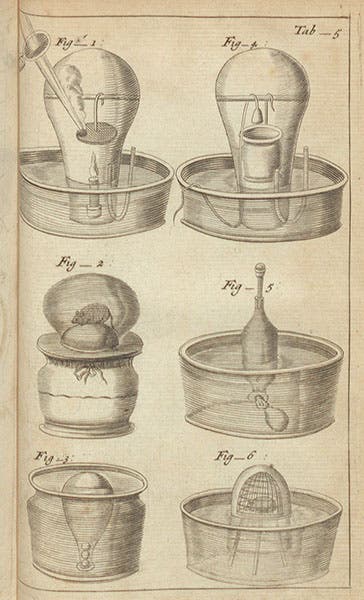

Mayow’s most famous experiment involved the calcination of antinomy (first image, a detail of fourth image). When he placed antimony in a flask inverted over water, and focused a burning glass on the antimony sample, it reacted (we are tempted to say it oxidized, but that term lay 100 years in the future) to form ��“calx of antimony,” and in the process used up a part of the air, because the water level rose in the flask. The calx was also heavier than the pure antimony, indicating that something had been added to the metal to form the calx. That something was nitro-aerial spirit.

Now that we understand the role of oxygen in combustion and respiration, it is easy to read a lot into Mayow’s experiments, and say that Mayow discovered oxygen, a century before the acknowledged discoverers, Joseph Priestly, William Scheele, and Antoine Lavoisier did so in the 1770s. But that was hardly the case; Mayow’s aerial nitre was something far different from oxygen, even if it was meant to explain the same phenomena. For example, Mayow explained the rise of the water level in the flask in the antimony experiment by arguing that the nitro-aerial spirit was responsible for the “spring of the air” (to use Boyle’s term); when you take it out of the air, the volume of air shrinks. We also know that many of Mayow's contemporaries, such as Boyle, Robert Hooke, and Kenelm Digby, were fond of talking about a nitre in the air that is essential for life, so Mayow was hardly unique in his argument or his terminology. Nevertheless, it is interesting that so many were grasping at oxygen a full century before its true nature was understood. Mayow had a better grip than most.

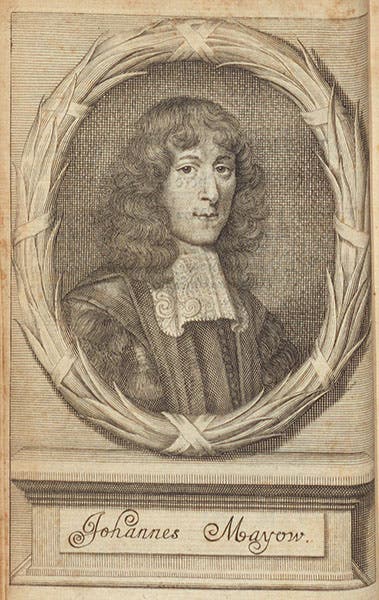

We have a 1681 edition of the Tractatus quinque, which is essentially a reissue of the 1674 edition, with an added title, Opera omnia, in our History of Science Collection. Our copy was once in the Library of the Royal College of Physicians of London, with its bookplate pasted onto the inside front cover. I do not believe that Mayow was a member of the RCPL – if he were, it would usually say so on the titlepage of his book. But apparently the Royal College of Physicians Library had enough copies of Mayow’s 1681 edition that they could afford to let one go as a duplicate. We are glad that they did.

The engraved portrait of Mayow (second image) appeared as a frontispiece to both the 1674 and 1681 editions of his Tractatus quinque.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.