Scientist of the Day - Joseph Huddart

Joseph Huddart, an English ship's captain, hydrographer, and inventor, died Aug. 19, 1816, at the age of about 76. Huddart was pretty much self-educated and self-motivated, teaching himself mathematics and model-building while a young man. His father started a business catching, smoking, and selling herring, and on his death, Huddart took over, and found he had an aptitude for ships and the sea. He built an entire ship all by himself and sailed it to North America around 1770, which is not something most young men manage to pull off. Soon thereafter, he joined the East India company as a ship’s commander and made four long trips to the East Indies. He made enough money to retire at the age of 48.

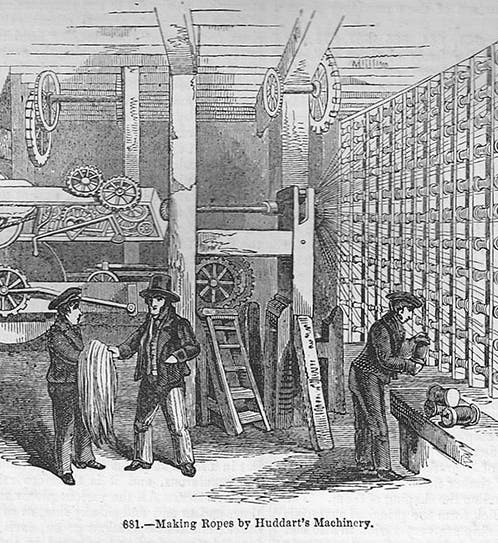

But his great contribution to the industrial revolution still lay ahead. Huddart had often noticed that the ropes on ships, which were made entirely by hand, were often deficient. He observed that the outer hemp fibers were usually under greater strain than the interior strands, so that outside yarns would snap first, and the rope would gradually fail from the outside in. What was needed was a way to ensure that all the fibers were under the same strain when the rope was fabricated. Huddart constructed a machine to do just that, eventually powered by a Watt-and-Boulton steam engine. When he tried to sell his invention to the Royal Navy, the Admiralty was not interested, so Huddart found investors and began building rope-making machines in Limehouse in east London. The rope-walk (as they call a rope-making factory) at Chatham Dockyard had been making rope the old-fashioned way for centuries; when they transitioned over to Huddart's machinery is not known (to me), but it is apparent they did, or William Walker would not have celebrated Huddart in the engraving discussed below, and Charles Knight would not have included an illustration of a Huddart rope-making machine in his various encyclopedias of the 1840s and 1850s (first image).

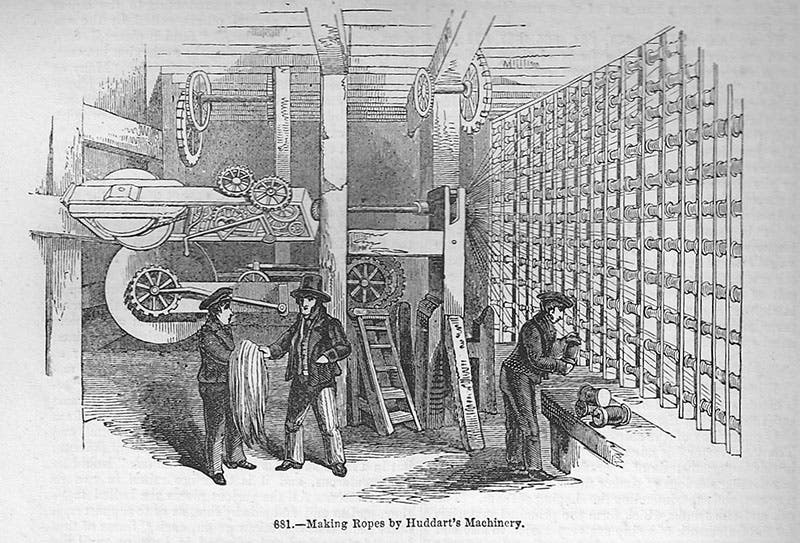

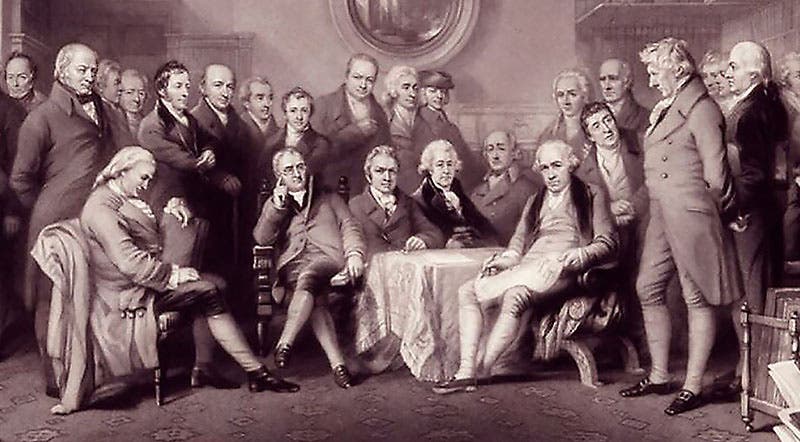

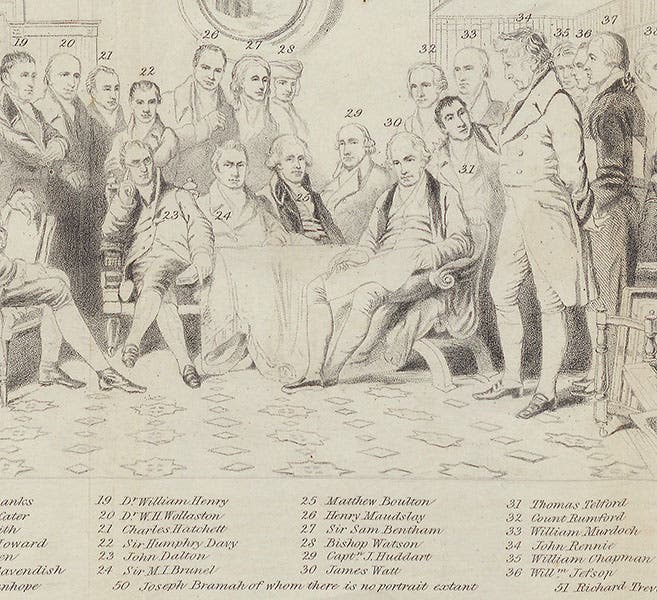

About three weeks ago, we featured an engraving and a book, both by William Walker, in this space. The engraving, published in 1862, was called “Distinguished Men of Science Living in 1807-08,” and the book, also published in 1862, was a Memoir that offered brief bios of the 51 men featured in the engraving, as well as a fold-out, reduced image of the engraving, with a key identifying each of the figures. One of the men so honored was Huddart. In the engraving in the National Portrait Gallery, from which we offer a detail (third image), Huddart is seated around the central table; he is the one furthest back, between Matthew Boulton, on the left, and James Watt, the right-most seated figure in the grouping. In the smaller engraving with labels and a key (see detail, fourth image), Huddart is no. 29, while Boulton is no. 25 and Watt is no. 30. Walker tells us that he drew his likeness from “the painting by J. Hoppner, in the possession of Charles H. Turner, Esq.” That painting is now in the Swansea Museum in Wales, and we include it as our second image. You can see the complete engraving of “Distinguished Men of Science” at our post on Walker, or in a zoomable version in the National Portrait Gallery.

The rope-walk at Chatham Dockyard is still in operation, and it was visited some years ago by a blogger, which we appreciate, because she included an image of Charles Knight's engraving of a Huddart rope-making machine, which we use as our first image here. We have Knight's 8-volume Arts and Sciences Encyclopedia in the Library, with a long article on rope-making, as well as a full run of his Penny Magazine, but I have not yet located this engraving. We have other Knight works – he was certainly prolific – so perhaps I will turn it up someday.

The Science Museum in London has a model of a rope-making machine in their collections (fifth image). Their description does not mention Huddart, but the model looks very much like the machine depicted by Knight (first image), so I suspect it has a connection to Huddart somewhere in its provenance.

Huddart was buried in the church of St. Martin's in-the-Fields, but I could not find any images of a memorial stone, if there is one.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.