Scientist of the Day - William Walker

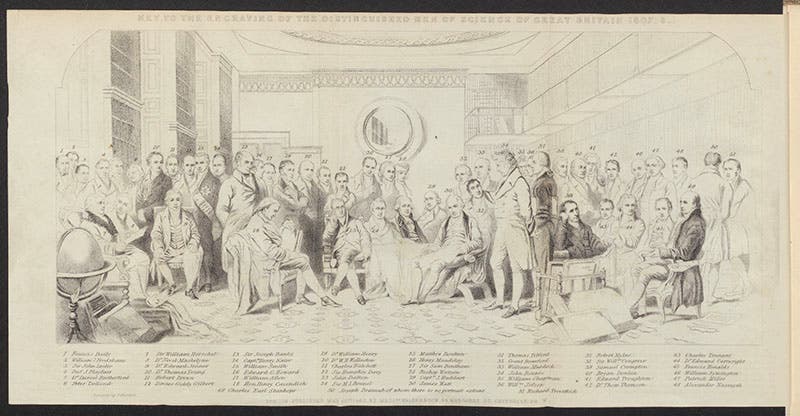

William Walker, Jr., a Scottish engraver and publisher, was born Aug. 1, 1791. Walker specialized in engraving portraits of such notables as Sir Walter Scott and Robert Burns, and he was apparently quite successful at his trade (there are 128 of his engraved portraits in the National Portrait Gallery, London). But in the 1850s, Walker conceived of something quite different: a group portrait of the 50 most eminent scientists of Great Britain, as of the year 1807-08. We don't know why he chose that year, except that, since he required that an individual, to be in the portrait, be alive at the time, perhaps 1808 yielded the maximum number of active living scientists. He had an artist do the initial sketch (which still survives) and then Walker, along with another artisan, did the engraving.

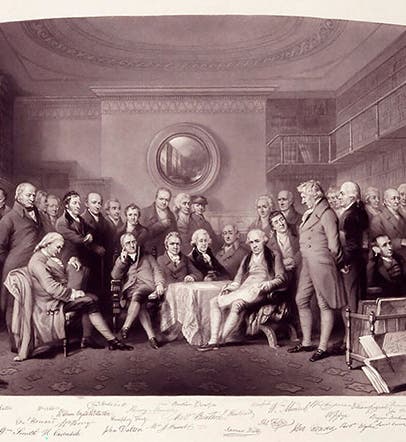

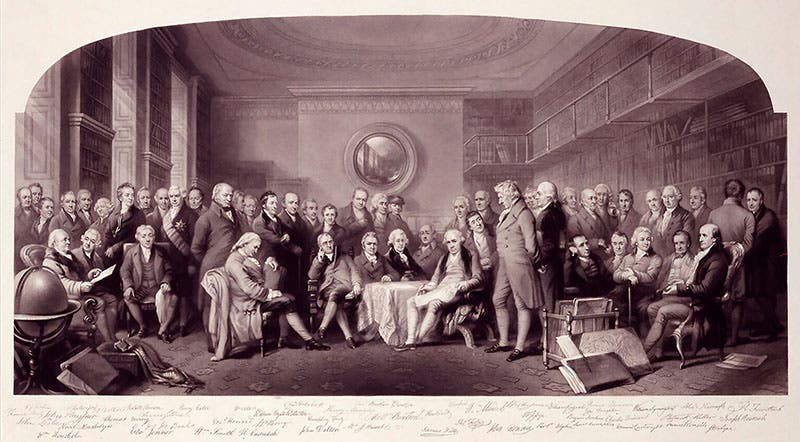

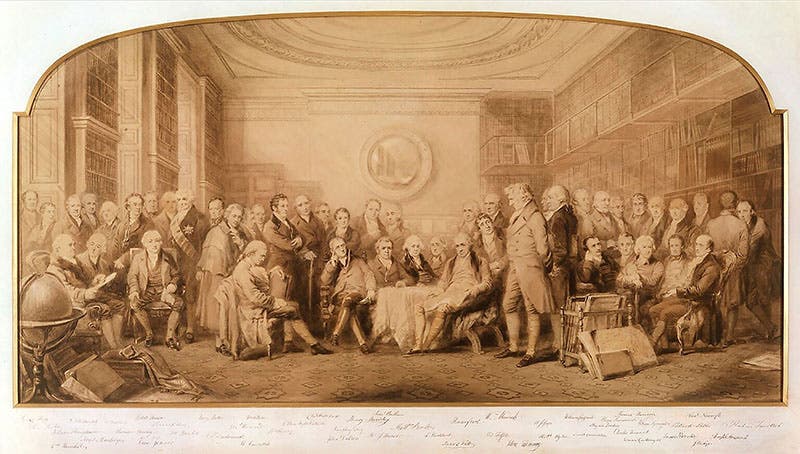

The engraving, Men of Science Living in 1807-8, is large (42 inches across), and very detailed, so it is not surprising that he spent 6 years on the project. It was finally published (by Walker) in 1862. There is a print in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in London (first image), and another in the Royal Institution of Great Britain (the setting for the fictitious group portrait). The NPG also has the original drawing for the engraving (second image), and an engraved key, which identifies each individual with a numbered label . Each portrait in the engraving was taken from existing individual portraits, so the scene is very lifelike, as if these 51 men did indeed assemble in the dining room of the Royal Institution one day just to have their picture taken. Some of the more recognizable figures are John Dalton, the father of modern atomism (leftmost of the 4 seated at the center table; see detail, third image), James Watt (center table group, at the right), and William Smith, the geological mapmaker (at the far left in the detail, third image), just behind the sleeping Henry Cavendish (if you look at the original pencil sketch (second image), you will see that Smith was not originally included, and was added later by Walker, at the expense of Archibald Cochrane, a chemist, who was put into solution, permanently).

We have borrowed details from the large engraving many times for these posts, such as William Henry, Davies Gilbert, and Joseph Bramagh, whom Walker included,, even though he could not find a portrait (see our post on Bramagh for Walker’s clever solution to the problem).

Group portraits of scientists, staged or real, are very scarce before the 20th century. I know of only a few other Victorian examples, one of which is The Arctic Council (1851), by Stephen Pearce, depicting all the Naval officers who searched for the lost Franklin expedition (this scene was also fictitious--there was no real gathering). My guess is that the success of Pearce’s painting and its subsequent engraving gave Walker the idea for his group portrait.

“Men of Science Living in 1807-8,” frontispiece engraving by William Walker, Jr., in his Memoirs of the Distinguished Men of Science of Great Britain Living in the Years 1807-8, 1862 (author’s collection)

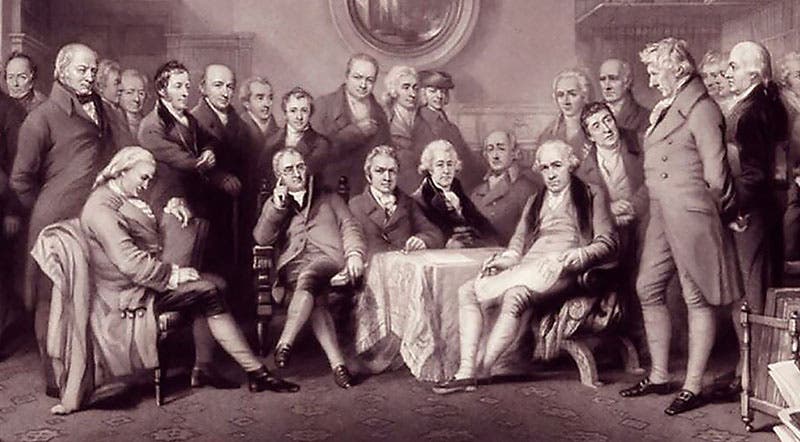

I knew our library would never acquire a copy of the engraving, because: a) it never comes on the market and: b) it would be very expensive if it did. I did not know that Walker had published a small version of the engraving (15” x 8”) as the frontispiece to a book, Memoirs of the Distinguished Men of Science of Great Britain Living in the Years 1807-8 (1862). But one day not long ago, the book popped up in response to a standing want I had posted for the large engraving. It was on a Saturday, and knowing that the book would be snapped up very quickly, I bought it myself; if I had waited until Monday to submit it as a possible Library acquisition, I knew it would be gone. So right now, I own it. But the Library will get it eventually, when I am gone.

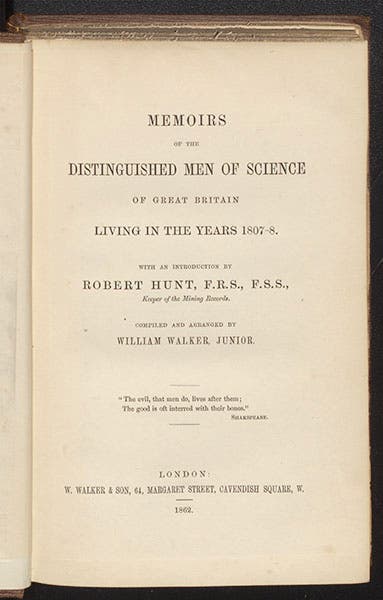

Title page, Memoirs of the Distinguished Men of Science of Great Britain Living in the Years 1807-8, by William Walker, Jr., 1862 (author’s collection)

The frontispiece in the book (fourth image) is not only smaller, but it has added numbers, and a key at the bottom. It is in fact the same keyed engraving that the National Portrait Gallery owns; either the NPG is unaware that it came from a book, or perhaps their engraving was sold separately and was never in a book. The latter might well be the case, since the NPG copy is slightly larger than mine.

First page of biography of Thomas Telford, Memoirs of the Distinguished Men of Science of Great Britain Living in the Years 1807-8, by William Walker, Jr., 1862 (author’s collection)

Aside from the engraving, the book contains short biographies of all the scientists depicted. Best of all, at the beginning of each biography, Walker tells us where he found the portrait that he used as a likeness, which makes it a very valuable resource for people like me who write illustrated biographies.

In addition to the complete engraved frontispiece to Walker’s book (fourth image) and the title page (fifth image), we also show the beginning of the biography of Thomas Telford (no. 31 in the engraving), where Walker informs us that he took his likeness from a portrait by Samuel Lane in the Institution of Civil Engineers (sixth image). We showed an engraved copy of that portrait in our post on Telford.

William was married to Elizabeth Reynolds, a fine miniature portraitist. She collaborated with William in drawing Men of Science Living in 1807-8, and William made mezzotints of many of her portraits, ten of which are held by the National Portrait Gallery. William and Elizabeth were buried in Brompton Cemetery in London. I am aware of only 4 people with a science connection who are buried in Brompton, whereas its sister cemetery, Kensal Green, has 22 that I know of. If there is something significant to be learned from this odd fact, it escapes me.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.