Scientist of the Day - Kenelm Digby

Kenelm Digby, an English courtier, natural philosopher, and occasional privateer, was born July 11, 1603. Digby was quite a piece of work: well-educated, good-looking, impressive in stature, family-wealthy, and a Catholic in an Anglican court. John Aubrey, whose collection of Brief Lives provides irrepressible glimpses of many 17th-century personae, said of Digby:

He was such a goodly handsome person, gigantique and great voice, and had such gracefull elocution, and noble addresse, etc., that had he been drop't out of the clowdes, in any part of the world, he would have made himselfe respected.

Because of his Catholicism, Digby spent many years in voluntary exile on the continent, especially in Paris, where he spent time in the company of Marin Mersenne, Thomas Hobbes, and Thomas White, the latter a fellow Catholic and English exile. Hobbes and White were atomists, which is to say they believed that matter is made of tiny indivisible particles, and that all properties, such as heaviness or heat, result from the arrangement and interactions of those atoms. Digby became an atomist himself. Atomists denied the independent existence of qualities such as dryness or gravity. Some atomists, such as Hobbes, even made the soul a material substance, although White and Digby stopped well short of that heresy. In 1644, Digby published Two Treatises: In the one of which, the Nature of Bodies; in the other, the Nature of Mans Soule, is looked into, which introduced the atomic philosophy into England. The Library has a second edition (1645) of this work.

In 1646, White published in Latin Institutionum peripateticarum; the title of the English translation is more revealing: Peripateticall institutions: In the way of that eminent person and excellent philosopher Sr. Kenelm Digby. We have the English translation (1656) in our collections. The professional curmudgeon Alexander Ross, who didn't like anybody except Aristotle, also published a book about Digby's atomism: The Philosophicall Touch-stone; or, Observations upon Sir Kenelm Digbie's discourses of the nature of bodies, and of the reasonable soule. In which his erroneous paradoxes are refuted (1645). You can see the titlepage of this book at our post on Ross. So, if you want to pursue a study of Digby's philosophy, our Library would be a good place to visit.

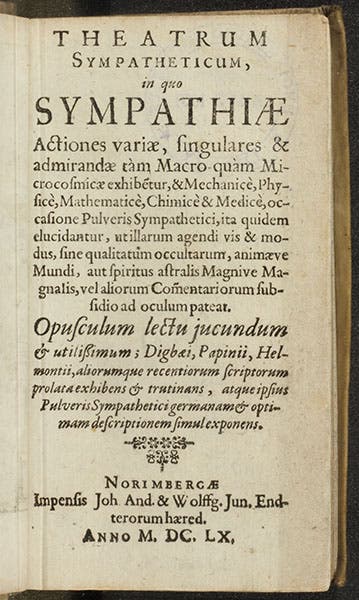

Digby is best known for a treatise he published in 1658 called A Late Discourse ... Touching the Cure of Wounds by the Powder of Sympathy. And yes, it is “powder,” not “power.” The sympathetic cure of wounds had been proposed a century earlier by Paracelsus, whereby instead of treating the wound, one applies a special salve or powder to the weapon that caused the wound, and the wound, by sympathetic connection with the weapon, is healed. Sympathetic medicine was explained by the Paracelsians as a magical cure; what distinguished Digby is that he sought to explain the effect mechanically, because he was, after all, an atomist who denied magical effects. His book was astoundingly popular and went through many editions; we have two Latin editions in the Library, with the title Theatrum sympatheticum (1660 and 1661). The folding frontispiece contains six vignettes that illustrate a variety of effects caused by sympathies. The most straight-forward is the one at left that shows two lutes on a table. If you pluck the G string on one lute, the G string on the other lute will vibrate, because the two strings have a sympathetic connection, a consonance, if you will. Our 1660 edition of the book has been digitized and is available online.

Every aspect of Digby's life is interesting. His father, Everard, was involved in the famous Gunpowder Plot of 1605 ("remember, remember, the fifth of November”) and was executed in 1606. Digby spent a year as a privateer in 1627, plundering French, Dutch, and Venetian ships off Gibraltar. In 1625, he married Venetia Stanley, who had been a courtesan and was as beautiful as Kenelm was handsome; he married her, he said, to save her from the brothel-house. Venetia had been kept by the Earl of Dorset, who provided her with an annuity; after she married Digby, the Earl declined to pay further, and Digby had the brass to sue him to continue paying 500 pounds per annum to his former concubine, and win! (or so says Aubrey, who should always be taken cum grano salis). The marriage was short-lived, as Venetia died in 1633, only 32 years old. Digby was disconsolate, and erected a monument to her memory, crowned by a bust; the monument burned in the Great Fire of 1665, although Aubrey said he saw the charred remains of the bust in a shop in the 1670s before it disappeared altogether. Digby had briefly converted to Anglicanism, but after Venetia’s death, he reverted to his old faith (Aubrey says: he looked back), which necessitated the move to Paris.

Digby was good friends with Anthony van Dyck, the Flemish-turned-English portrait painter; the two often performed alchemical experiments together. One result of this friendship is that there are quite a few portraits of Kenelm by van Dyck; we show one painted in the early 1630s, in the Royal Museums Greenwich (first image), and another, painted about 7 years later, in the National Portrait Gallery, London (fourth image). Van Dyck also did several portraits of Venetia, including one as Prudence, in the National Portrait Gallery, which you can see here.

Digby returned to England upon the restoration of Charles II and helped found the Royal Society of London. He died on June 13, 1665, and was buried in his wife’s tomb at Christ Church Greyfriars Churchyard, London.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.