Scientist of the Day - Parsons and Boeddicker

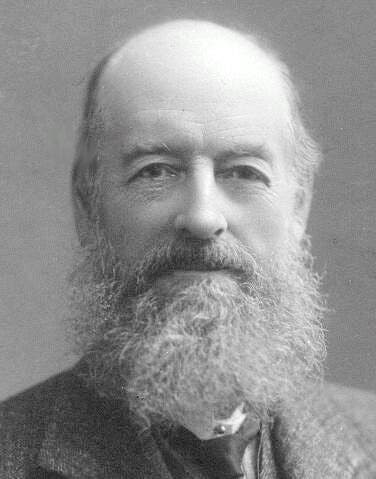

Lawrence Parsons, the 4th Earl of Rosse and an amateur astronomer, was born Nov. 17, 1840, at Birr Castle in Ireland. His principal assistant at the Birr Castle Observatory was Otto Boeddicker, who was born Nov. 17, 1853, in Germany, and came to work for Parsons in 1880. One hopes they had some exciting parties on the castle grounds on their mutual birthday, Nov. 17.

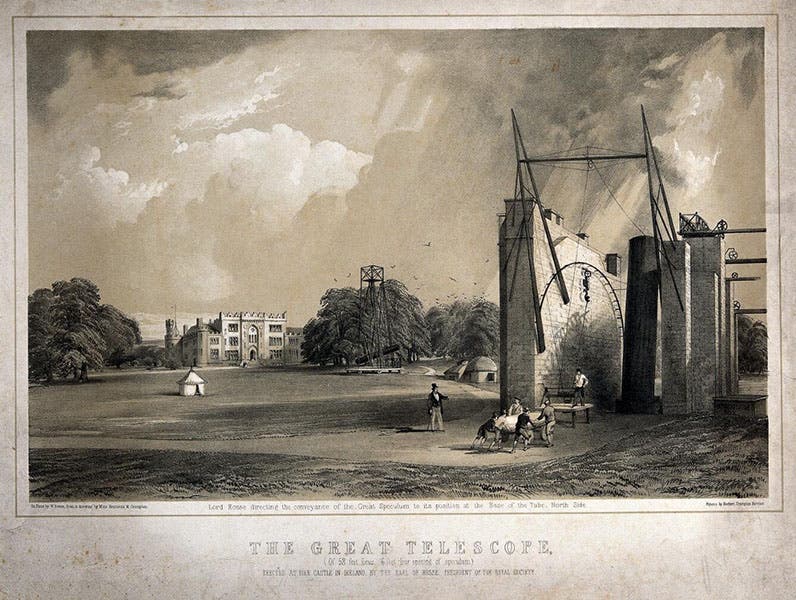

Parsons inherited the Observatory from his father, the 3rd Earl, William Parsons, who constructed a mammoth 72-inch reflecting telescope on the grounds of Birr Castle in 1844 (fourth image). It was the largest telescope in the world for 72 years, and with it, the elder Parsons discovered the spiral nature of some nebulae, most notably the Whirlpool Nebula, M51. You can see images of the third Earl, the completed telescope, and M51 at our post on William Parsons.

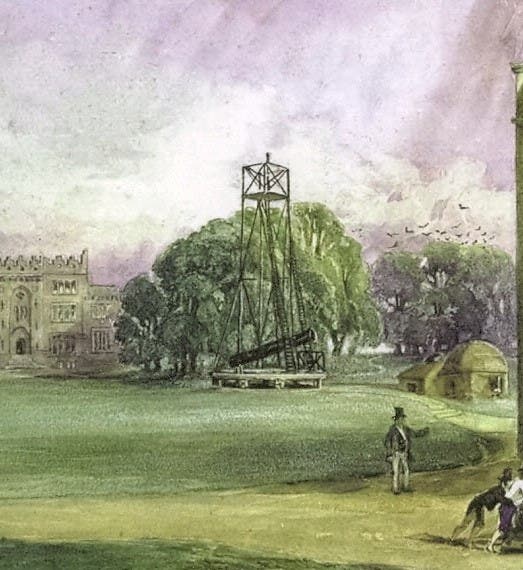

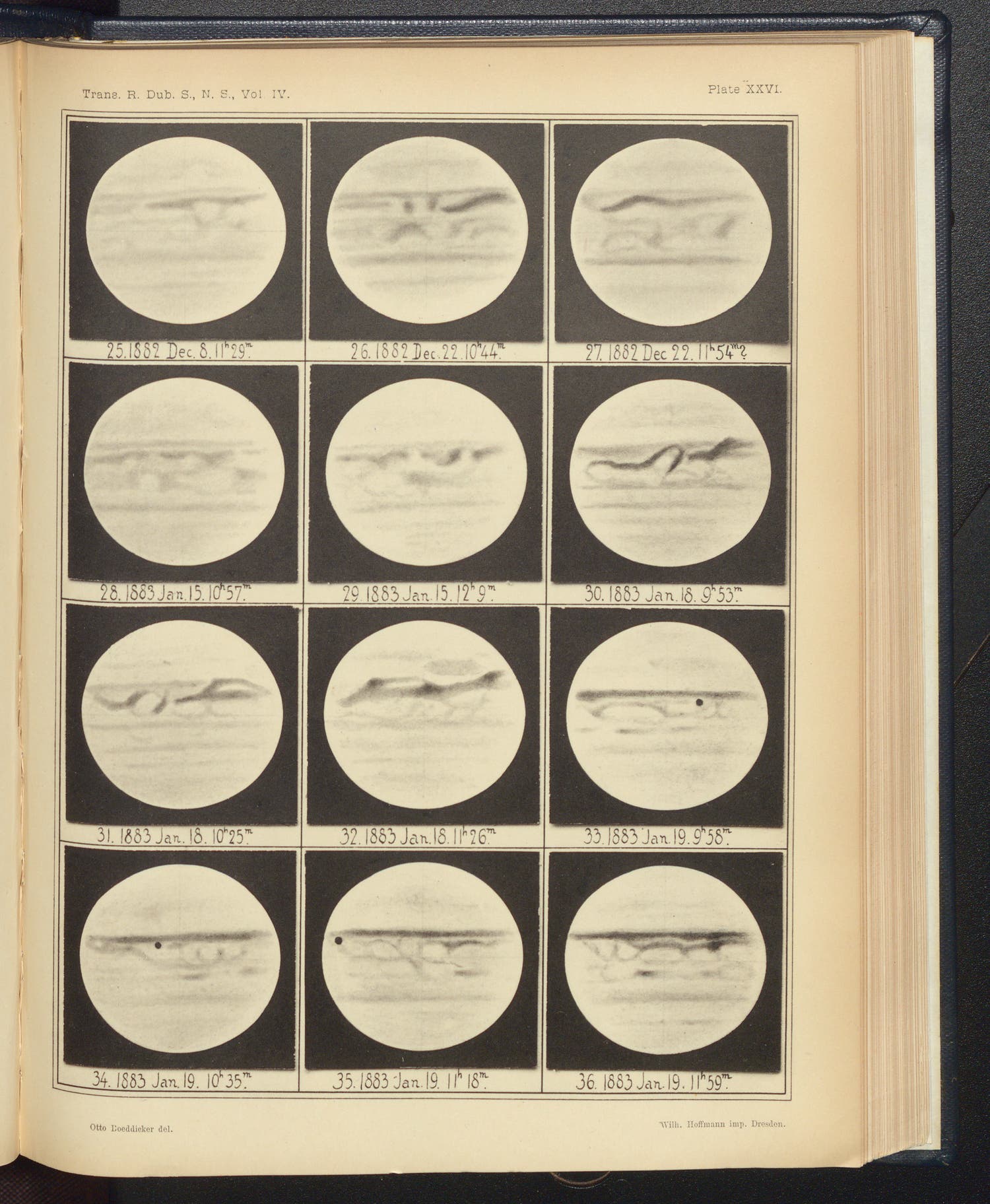

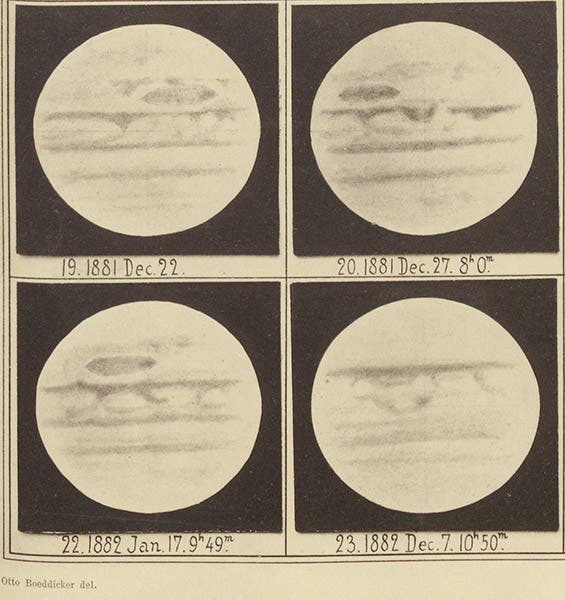

Lawrence was not nearly as ardent an amateur astronomer as his father, but he kept the telescopes operating, both the “Leviathan” (the big one), and a 36-inch refractor that was much easier to use, and quite large enough for most practical purposes. In a detail of a watercolor of the Birr Castle grounds, one can see the 36-inch reflector in the background (first image). To do the actual observing, he hired Boeddicker (third image). We know very little about Boeddicker before he came to Birr Castle, and not much more about him after he arrived. But he did publish some of the results of his observations, and we have those publications. He spent part of his first six years making regular observations of Jupiter with the 36-inch telescope, recording what he saw in delicate drawings. In 1889, he published 84 of those drawings on 7 lithograph plates in the Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society. They were collectively the finest drawings of Jupiter made to that time, and they were reproduced, says Boeddicker, by a photo-mechanical process, so that the prints were true to the originals. We show a complete plate, with 12 drawings of Jupiter made in 1882-83 (fifth image). The ever-changing belts and bands are well-drawn, and note that in four of the drawings at the bottom, the shadow of one of the Galilean moons is evident.

Some of the other drawings capture the Great Red Spot of Jupiter. This feature had been discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini back in 1665, and then it disappeared, only to re-emerge in 1871. There are no good modern drawings of the Great Red Spot before those of Boeddicker. It is especially well-represented at the bottom left of our sixth image.

Boeddicker later published a set of drawings of the Milky Way made with the naked eye: The Milky Way, ... drawn at the Earl of Rosse's Observatory at Birr Castle (1892), that we also have in our collections. We shall save it for a further post.

Parsons left most of the astronomy to Boeddicker. But when he had just inherited Birr Castle and the Observatory, in the late 1860s and early 1870s, he appears to have done some observing himself, for in 1873, he discovered his own spiral nebula. It doesn’t have a fancy nickname, like the Whirlpool Nebula, but it does have a label, NGC 2, meaning it is the second object in the New General Catalogue of nebulae, published in 1888. It is no. 2 only because its right ascension, a measure of its position in the sky, is near zero, and the catalogue is ordered by right ascension. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey has now provided us with a pretty photograph. NGC 2 is in the center; the more prominent NGC 1, just above, was discovered earlier.

Lawrence went on to become Chancellor of Trinity College, Dublin, for 23 years, leaving the daily operations of the Observatory to Boeddicker. I do not know what Boeddicker did after Lawrence died in 1908; he might well have stayed on to serve the 5th Earl. But we do know that, shamefully, Boeddicker was declared an undesirable alien in 1916, after England entered World War I, and he left the country. His further fate is unknown. The one photograph that survives of Boeddicker (third image) has no documentation, but since it is all that we have, we will assume it is valid until shown otherwise.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.