Scientist of the Day - Lazzaro Spallanzani

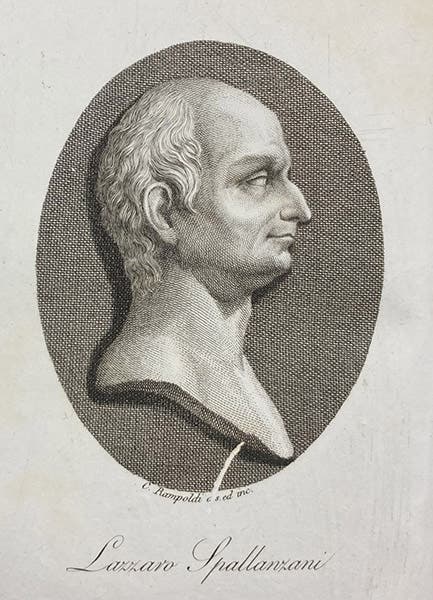

Lazzaro Spallanzani, an Italian biologist, geologist, and priest, was born on Jan. 12, 1729, in Scandiano in north-central Italy, near Regio Emilia. He attended the University of Bologna, studying law and philosophy, and taught philosophy at the Universities of Regio and Modena, before switching fields and moving to the University of Pavia in 1768 as professor of natural history.

Spallanzani was one of the few students of the life sciences in the 18th century whom one might call a biologist, for he was interested in the nature of life itself, and in what was called generation, the process by which life arose and traits were passed on to the next generation. In particular, he wondered about spontaneous generation, the sudden appearance of living things from non-living matter.

The subject was an old one; Aristotle had accepted the fact that insects and other primitive life forms could arise spontaneously, and so did nearly everyone else until the middle of the 17th century, when William Harvey suggested in 1651 that all living things arose from eggs. Shortly after Harvey, the microscope was introduced, and investigators like Robert Hooke and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek discovered that life exists on a microscopic scale and is everywhere, in every drop of water. It seemed very possible that simple living things did indeed arise spontaneously. So, in 1668, the question was approached experimentally, by Francesco Redi.

Redi did a famous set of experiments in which he exposed some vials of decaying meat to the air, while covering others with fine mesh. He found that insects arise in the exposed meat but not in the covered vials, demonstrating that if you could keep insects away from rotting meat, no new insects appeared, and suggesting that even insects arose from eggs laid by parent insects.

But spontaneous generation would not be easily dismissed. Insects might arise from eggs, but what about those microscopic life forms, what Leeuwenhoek called animalcules that were found everywhere.

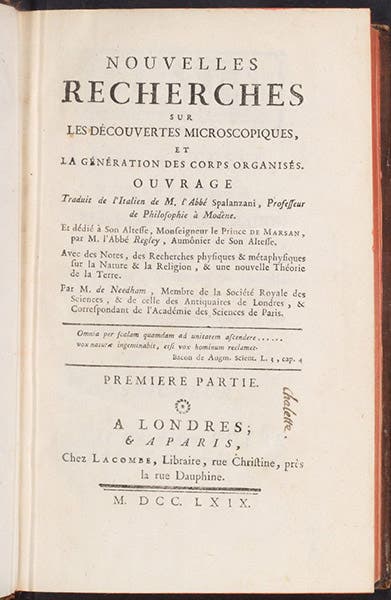

The question was taken up anew by John Turberville Needham, an Englishman working in Paris, who did experiments in the late 1740s, for which he sealed up aqueous solutions containing organic material and heated them to kill any eggs, and he found that microscopic life appeared anyway. It would seem there was some vital force in nature, some life-force, that could create simple life forms, no parents required. Georges Buffon agreed.

Spallanzani questioned Needham's results. He redid all of Needham's experiments, but he did them better. And he showed that if you sealed things properly, and sterilized them rigorously, no life forms would appear in the sterilized solutions, until you exposed them to the air, when they suddenly began to teem with life, suggesting that microscopic seeds and eggs are necessary for such blooms.

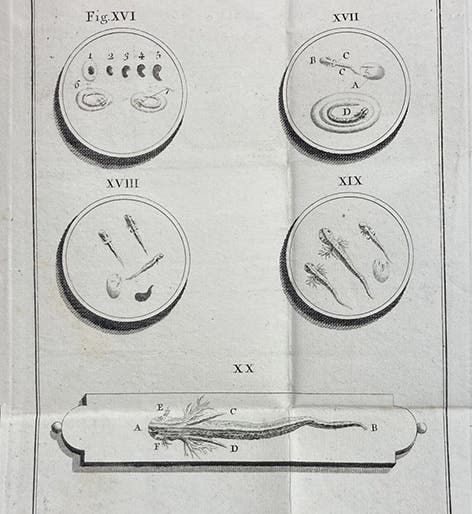

Spallanzani sounded the death knell for spontaneous generation in a book, Saggio di osservazioni microscopiche concernenti il sistema della generazione de' signori di Needham e Buffon (1765). Needham then translated Spallanzani’s book into French and added extensive notes in an attempt to rebut it in 1769. We have Needham's translation in our collections (third image), but not Spallanzani's Italian original. I hope we can acquire it in the not-too-distant future.

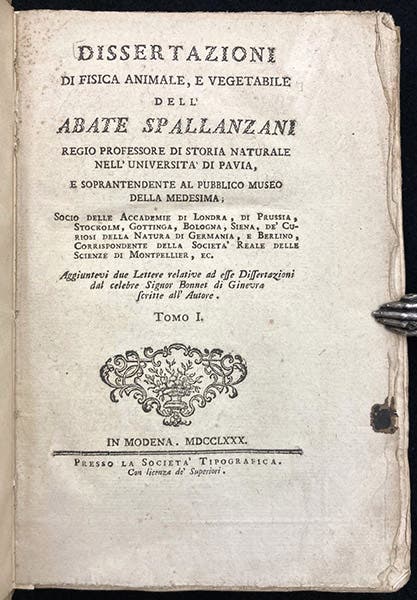

We do have Spallanzani's Dissertazioni di fisica animale e vegetabile in our collections, the source of our first image, and various translations of that 2-volume work. We also have multiple editions of his Viaggi alle Due Sicilie e in alcune parti dell' Appennino (Voyage into the Two Sicilies, 1792-97), in which he moved from biology to geology and considered the origin of igneous rocks such as basalt. We might look into Spallanzani's contribution to the study of vulcanism, a hot topic in late 18th-century Italy, at a future date.

Spallanzani died in Pavia on Feb. 11, 1799, and was buried there. Louis Pasteur, who finally put spontaneous generation to rest in the 1860s with his work in bacteriology, had a full-size portrait of Spallanzani in his workspace. I wonder where that ended up? There is a good-looking statue of Spallanzani in his hometown of Scandiano (last image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.