Scientist of the Day - Libert Froidmont

Libert Froidmont, a natural philosopher and theologian of Liège and Louvain (Leuven) in the Spanish Netherlands (now Belgium), died Oct. 28, 1653, at the age of 66. Froidmont played an interesting role in the reception of Copernicanism in the Netherlands. Trained by the Jesuits, and thus an Aristotelian in matters of natural philosophy, Froiedont was neverthess receptive to new ideas and discoveries, such as the Copernican proposal that the Earth is a planet moving around a central Sun or Galileo's discovery that the Moon is blemished with craters and Jupiter has four moons that orbit around it. Froidmont’s initial enthusiasm was however tempered by the events of 1616, when heliocentrism was declared heretical and the book of Copernicus was banned until it could be corrected to conform to Church doctrine. It wasn't that Froidmont was frightened or intimidated by the actions of the Inquisition. Rather, he was concerned that advocates of the new cosmology were acting rashly in disregarding the weight of tradition in interpreting Scripture. He thought there were ways to reform astronomy without requiring a reinterpretation of Scripture, as people like Galileo were advocating.

We have two books by Froidmont in our collections. The first is called Meteorologicorum libri sex (Six Books on Meteorology), essentially a commentary on Aristotle’s Meteorology. We show the title page below – there are no illustrations at all in the work. This book is not about weather, but rather about the sublunary or elementary world, the part of the cosmos that is not heavenly. This was the traditional domain of meteorology, as established by Aristotle. Aristotle had placed comets in the sphere of fire below the Moon, and so he discusses comets in his Meteorology. Froidmont was convinced, from the work of Tycho Brahe, that some comets are super-lunary and thus heavenly bodies. But otherwise, there is not much discussion of Copernicanism in Froidmont’s Meteorology.

But Froidmont began to take a closer look at Copernicanism when a Dutch astronomer, Philippe van Lansberge, began to argue strongly in favor of a sun-centered universe, especially in his 1630 book, Commentationes in motum terræ diurnum & annuum (Commentaries on the daily and annual motion of the Earth), a book we have in our collections. Lansberge was an unabashed Copernican, but he was also a Protestant, so didn't have to concern himself with decrees of the Inquisition. Froidmont disagreed with the dogmatism of Lansberge, and he wrote a response, Ant-Aristarchus (Against Aristarchus [an ancient philosopher who proposed a sun-centered universe], 1631). We do not have this work in our collection, but Froidmont apparently argued that there are many logical reasons, and much evidence from our senses, that makes the motion of the Earth a difficult proposition.

Lansberge’s son, Jacques, wrote a defense of his father against Froidmont in 1632, and Froidmont responded with his Vesta, sive Ant-Aristarchi vindex (Vesta, or a Vindication of Ant-Aristarchus, 1634). This work we do have. Froidmont mostly repeated his arguments of 1631, but he did have new ammunition – in 1633, Galileo was forced to abjure his Copernican beliefs by the Inquisition, and his book, Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems (1632), was placed on the Index. So, in addition to the arguments from Reason, the Senses, Tradition, and Scripture against Copernicanism, Froidmont could add the mandate of Church Authority, which now said that we cannot teach or advocate heliocentrism as truth. Froidmont, however, had no problem with discussing or teaching Copernicanism, as long as it was regarded as only a hypothesis.

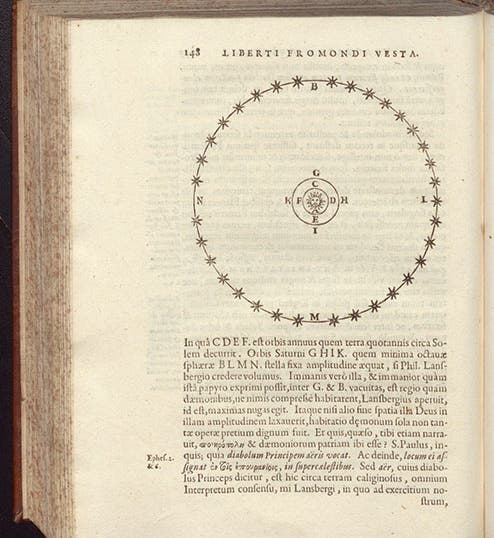

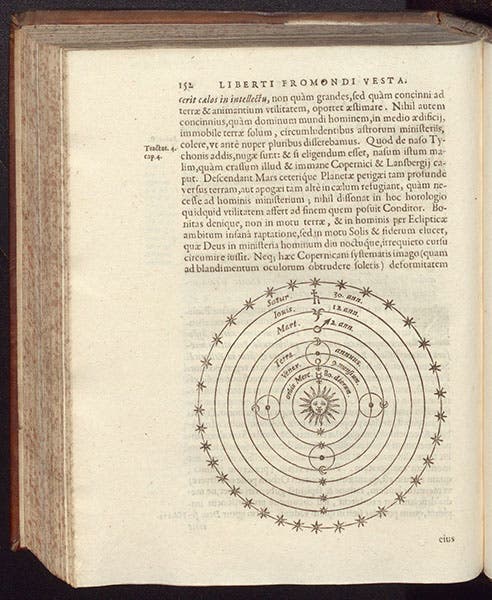

One of the best arguments against heliocentrism, which was not original with Froidmont but which he did discuss and illustrate in his 1634 book, is the problem of the space between the planets and the stars. In a geocentric cosmology, the sphere of stars can be placed just outside the sphere of Saturn, the outermost planet, and the cosmos looks like a tidy nest of spheres. The Copernican cosmology is often pictured this same way – Copernicus himself did so, and Froidmont provided a redrawn copy of that diagram (fifth image). But in reality, if the Earth moves, then the stars must be much, much further away than Saturn, or else we would see stellar parallax, a wobbling motion of the stars caused by the annual motion of the Earth. And we see no parallax at all. So a proper drawing of a Sun-centered system would have all the planets near the center, and then a huge void between Saturn and the stars. Froidmont gave us just such a diagram in his Vesta (first image), and it is probably the most memorable illustration in his book.

I find Froidmont to be one of the most sympathetic opponents of Copernicanism in the period following the condemnation of Galileo. He was really excited by new cosmological ideas. But he deeply believed that Scripture and Church tradition were to be respected, and Church authority was to be obeyed. That was the nature of his faith. And so he acted in the only way he could, embracing novelty for discussion purposes, but requiring that it be compatible with established religious beliefs.

The one surviving portrait of Froidmont is a memorable one (second image). It is in a museum in Visé, a city just northeast of Liège in eastern Belgium, near where Froidmont was born. I have not been able to identify the artist, or the date of the portrait.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.