Scientist of the Day - Louis Figuier

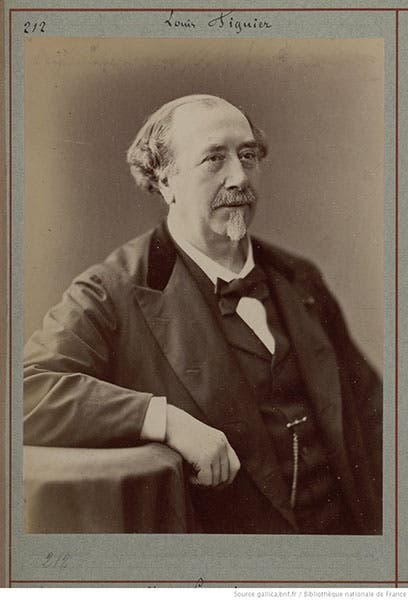

Louis Figuier, a French writer on popular science, died Nov. 8, 1894, at the age of 75. Figuier had a degree in pharmacy, but he apparently took the losing side of a disagreement with Claude Bernard in the 1850s, and he transitioned from a scientific to a literary career, writing about science instead of practicing it. He was extraordinarily good at his new vocation, becoming, with Camille Flammarion, one of the most widely read popular science writers in France in the last four decades of the nineteenth century. His most significant and (in the long term) most influential book was probably Les merveilles de la science (The Marvels of Science, 1867-91), a 6-volume work that was one of the first popular histories of scientific achievement, and certainly the best illustrated. We wrote a post on Figuier four years ago, where we focused on the Merveilles, and showed four original illustrations that still pop up in modern histories of science.

Two other Figuier books of note dealt first with the prehistoric world in general, and then with primitive humans. The first book, La terre avant le deluge (The Earth before the Deluge) was published in 1863, and there really had never been a book like it, one that not only described, say, the Cretaceous and Jurassic periods, but illustrated these early stages of life of Earth. The book sold out its initial printing immediately, and went through a second edition that same year, and then two more in 1864, and a fifth in 1866. We have all these editions in our collections. The book was translated into English in 1865, and reprinted in 1867, and we have both of those as well. Many of the plates were drawn by Edouard Riou, who had just illustrated a book by Jules Verne and was in the process of illustrating two more. The illustrations of dinosaurs in Figuier’s book are especially memorable. You can see three plates from the first edition in a post on Riou that we published many years ago, including one memorable engraving that depicts Iguanodon and Megalosaurus, the first two dinosaurs to be discovered, doing battle in a lower Cretaceous swamp.

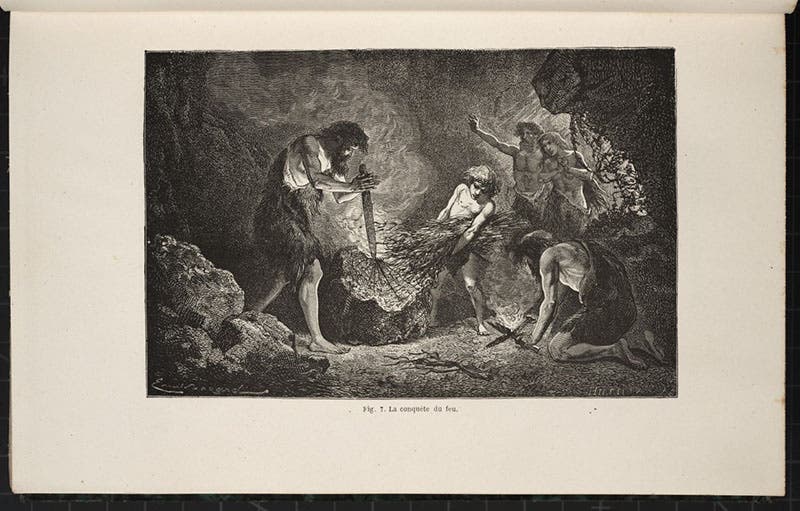

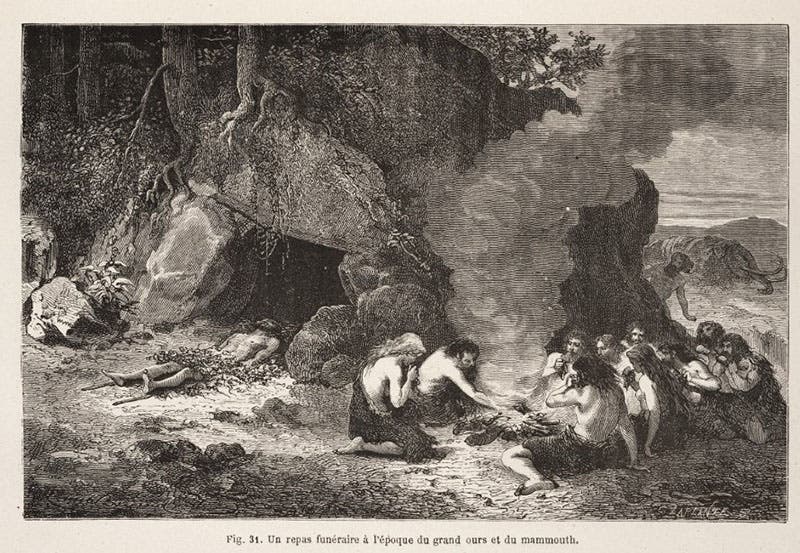

In 1870, Figuier published a follow-up book to La terre avant le deluge, called L'homme primitif (Primitive Man). In a manner similar to that of its predecessor, it told the story of human prehistory with engravings and explanatory text. The book was translated into English that same year; we have both 1870 editions in our collections. There had never before been an attempt to show the different stages of human culture until Figuier's book. We show here a few of the 30 wood engravings in the work, which were based on drawings by Emile-Antoine Bayard, who would that same year illustrate Jules Verne’s Autour de la lune (Around the Moon, 1870), which was the subject of a post on Bayard.

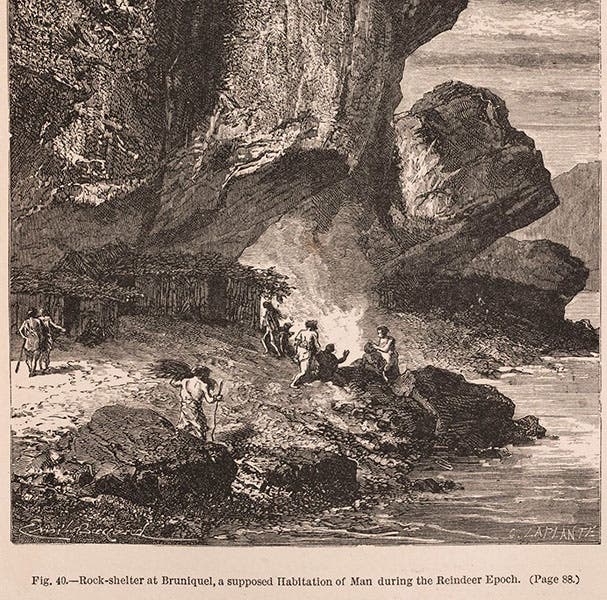

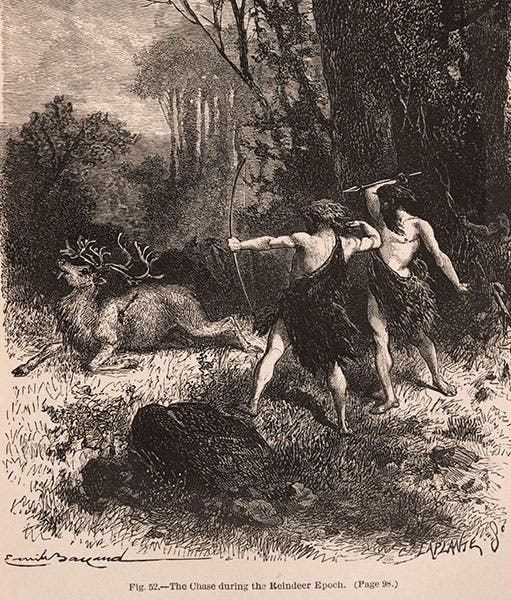

We include here plates, taken from both the French and English editions of L’homme primitive, that show such scenes as life in a rock shelter, the conquest of fire, a human burial during the Epoch of the Great Bear (cave bear) and the Mammoth, hunting during the Epoch of the Reindeer, and being hunted by cave bears. To appreciate these, you must understand that the terms Reindeer Epoch, Cave Bear Epoch, and Mammoth Epoch were very recent introductions, as were the terms Paleolithic and Neolithic. The idea of human antiquity – that humans had lived on Earth during periods when it was populated by animals now extinct – had been an acceptable idea for only a decade when Figuier published his book. Although Neanderthal, a different-looking kind of human, had been discovered in 1856, he was far from being accepted as a human ancestor in 1870. So Figuier’s book was very much on the cutting edge of contemporary anthropology. The illustrations opened up an entirely new world to readers.

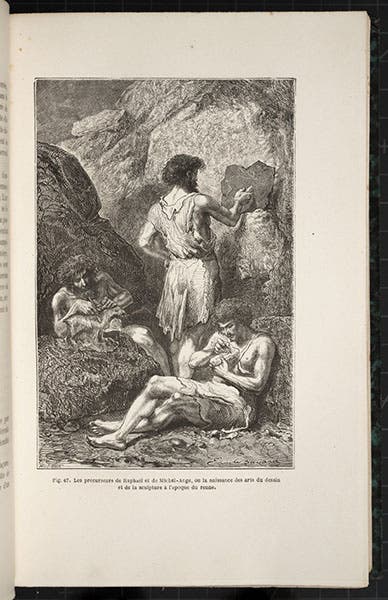

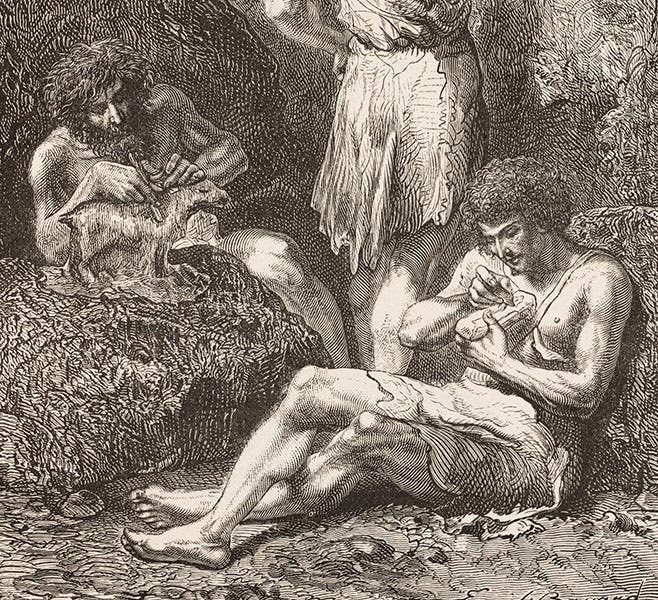

My favorite illustration is one that is captioned, in the English edition, “Arts of drawing and sculpture during the Reindeer Epoch” (eighth and ninth images). In 1870, examples of prehistoric cave painting had yet to be discovered, but there were several known examples of carved bone art, such as the mammoth of La Madeleine, and that inspired Bayard to recreate a stone-age atelier in a cave. I also like the more expansive caption to this wood engraving in the French edition, which translates as “The precursors of Raphael and Michelangelo, or the birth of the arts of design and sculpture during the Epoch of the Reindeer.”

We displayed a portrait of Figuier as the 5th image in our first post on Figuier, which is included in our copy of Les merveilles de la science. For this occasion, we reproduce a photograph of Figuier by the great Nadar that is in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.