Scientist of the Day - Matteo Ricci

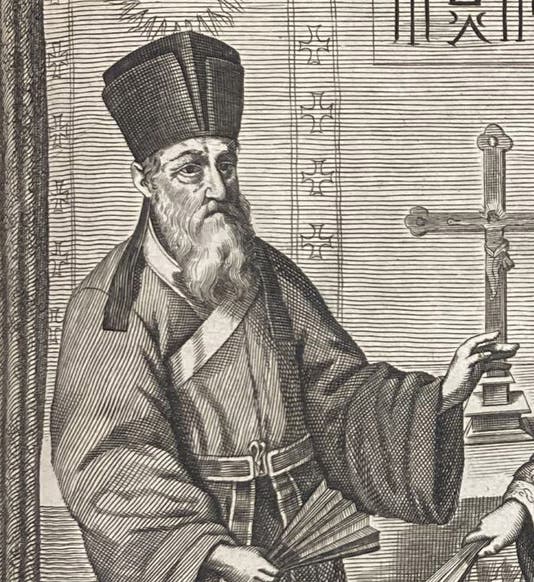

Portrait of Matteo Ricci, detail from a larger engraving, China monumentis… illustrata, by Athanasius Kircher, p. 114, 1667 (Linda Hall Library)

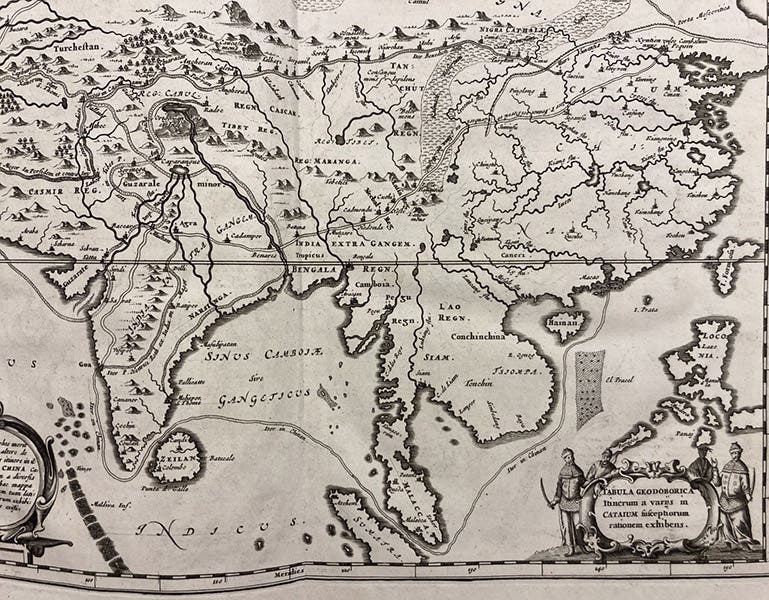

Matteo Ricci, an Italian/Chinese Jesuit missionary and mathematician, was born Oct. 6, 1552, in Macerata, in the Marches of Italy. He joined the Society of Jesus in 1571 and studied at the Collegio Romano, where he absorbed the geometrical and astronomical teachings of Christoph Clavius. Ricci decided on the life of a missionary, a Jesuit specialty, and sailed to Goa in India in 1578 (see map, second image). Four years later, he was transferred to the Portuguese port of Macau on the southern edge of mainland China. Here began a 28-year sojourn that would culminate in an Imperial invitation to the Forbidden City in Peking.

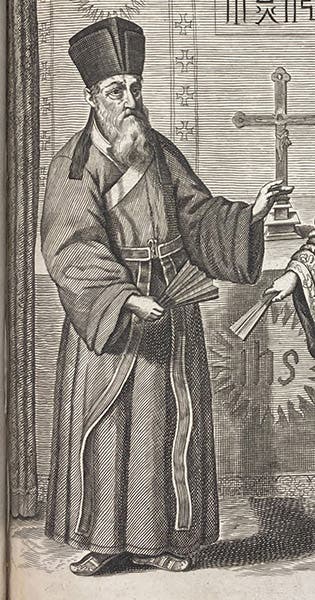

Map showing the route taken by Ricci from Goa on the west coast of India to Macau, on the southern coast of China, detail of a larger engraving, China monumentis… illustrata, by Athanasius Kircher, p. 12, 1667 (Linda Hall Library)

The hard part was to get out of Macau and into China. Ricci managed this by learning to speak Chinese and to read and write the classical form of the language. He then sought to use mathematical science – such things as eclipse predictions – to demonstrate the utility of western science. Since he could speak the language, he was able to impress various officials in cities to the north of Macau, and he got new assignments that took him slowly northward toward Nanjing and Peking.

One thing that really impressed local officials, mandarins, and eventually members of the imperial palace, were mechanical devices, such as astrolabes, quadrants, and clocks. They were especially enthralled by mechanical clocks that struck the hour. The Chinese had nothing like that, and were fascinated. Ricci also brought with him editions of Clavius’s Euclid, and had it translated into Chinese. There was no Chinese equivalent to Euclid’s Elements.

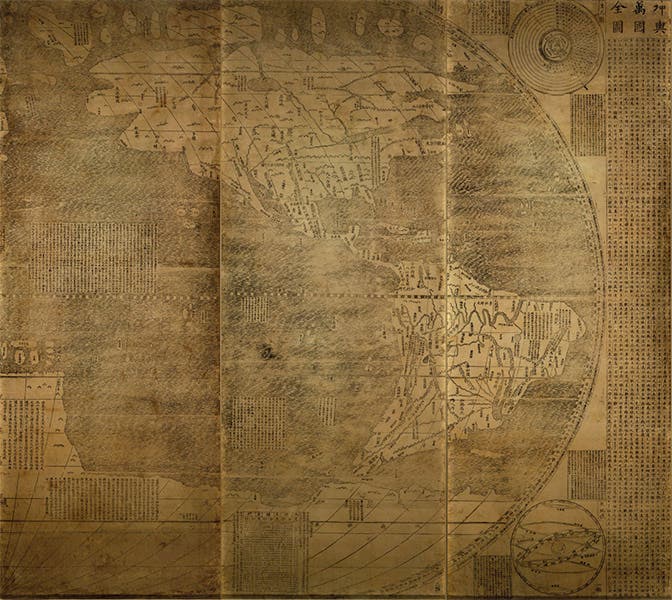

Ricci also brought with him several world maps, including the 1570 map of Abraham Ortelius. In 1584, he was asked if he could construct a world map with labels and legends in Chinese. He made such a map, but it was never printed. Eighteen years later, he produced a revised map, and this one was printed in 1602, at the special request of the Emperor. It was called the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, and was the first world map printed in Chinese. It was quite large, printed in 6 vertical strips for a total width of 12.5 feet. Only 7 copies of the Ricci world map suvive. The only one in the New World is in the James Ford Bell map library at the University of Minnesota. You can see the entire map at this link; we show here a detail of the three sections that contains North and South America, courtesy of Jeremy Norman’s History of Information website (third image).

In 2010, the Library of Congress exhibited the James Ford Bell copy of the Ricci 1602 world map, alongside the LoC copy of the Waldseemüller world map of 1507, the first to show “America.” Amazingly, they still have an active webpage that describes the Ricci map.

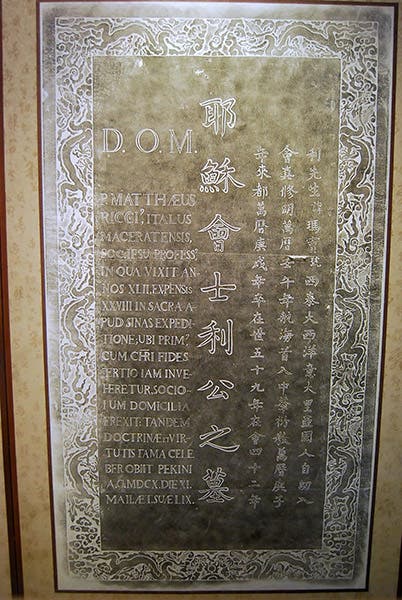

By imperial decree, foreigners who died in China (there were not many) had to be taken to Macau for burial. When Ricci died in 1610 in Peking, the Jesuit delegation made a special appeal to the imperial staff that Ricci be buried in Peking. It was a bold and unprecedented request, and surprisingly, the appeal was successful. A small plot of land in Peking was set aside as a Jesuit cemetery, called the Zhalan Cemetery, and Ricci was the first person interred there (fourth image). The cemetery was later attacked and defaced several times, during the Boxer rebellion and the Cultural Revolution, but Ricci's monument still stands, directly behind the entrance portal, with an inscription in both Latin and Chinese (fifth image). Several later Jesuit scientific missionaries, Ferdinand Verbiest and Adam Schall von Bell, are buried there as well. We will profile both at some future time.

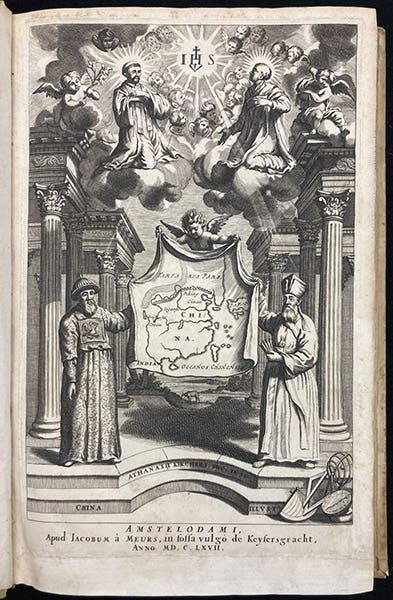

In 1667, a Jesuit scientist several generations down the line, Athanasius Kircher (he was born the year Ricci's world map was issued, 1602), published his own book on China, China monumentis… illustrata. Since Kircher never left Rome, he relied heavily on books by Ricci and others. Perhaps by way of thanks, he included several engravings of Ricci. We show here the engraved title page, with Ricci on the right (and Schall von Bell on the left; sixth image). Kircher’s book was also the source for our initial portrait, and for the map of China (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.