Scientist of the Day - Matthew Hale

Matthew Hale, an English judge, jurist, and barrister, was born Nov. 1, 1609. Hale is quite well known in the annals of legal history, having written influential treatises on the history of English common law and on crimes against the crown. He was a Royalist who managed to serve through the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell and into the reign of the restored King Charles II, primarily because he had unquestioned integrity and was regarded by all as eminently sensible and rational.

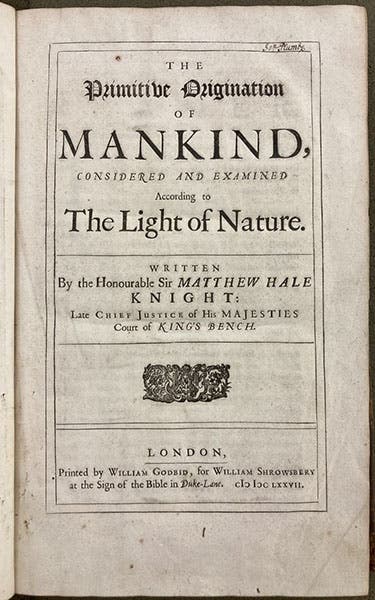

Hale was not a natural philosopher or a naturalist, but he merits inclusion as a Scientist of the Day, because of an unusual book he wrote and published, The Primitive Origination of Mankind: Considered and Examined according to the Light of Nature (1677). Hale lived in an era when atomism, the revived philosophy of Democritus, Lucretius, and Epicurus, was enjoying popularity in England. During the late Renaissance, atomism was dismissed by just about everyone as an atheistic philosophy, but the French philosopher Pierre Gassendi had not only embraced atomism, but he had Christianized it, denying that atoms had existed since eternity and stipulating that the existence of atoms requires a God to create the atoms and to imbue them with motion. Gassendi's Christian atomism was imported into England by Walter Charleton, in his Physiologia Epicuro-Gassendo-Charletonia (1654), an English popularization in spite of its mouthful of a Latin title. Thomas Hobbes was an influential atomist, although of atheistical tendencies, and so were many others.

One of the tenets of atomism was the belief that living things originated spontaneously from inorganic matter, through the intermediary of "seeds,", spontaneous congregations of atoms that could give rise to living organisms. This was anathema to orthodox Christianity, which considered the creation of life a divine act, as described in Genesis. Hale was certainly an orthodox Christian, but unlike most of his fellow believers, he took it upon himself to refute any claims to a natural origin for humankind. Hence the book, which he compiled in his last days, and which was published the year after his death.

We have an attractive copy of The Primitive Origination of Mankind in our collections, a large quarto, still bound in its original calf, unobtrusively rebacked. The book is unsullied by any illustrations except for the portrait frontispiece, and in other hands would be a formidable read, but in this case not so, as Hale was a graceful writer. HIs principal concern was to defend the Scriptural account of the origin of humans as the most plausible, rational, and conformable to experience. He presented the arguments of the atomists in detail, and quite fairly, but then argued that the atomist claims were quite incredible, unbelievable even, compared to the account in Genesis.

One of the most interesting sections of the book considers the fact that the Americas are populated by both humans and animals. This was a grave problem for Christian apologists, as it seemed difficult to imagine how animals got to the New World, came back to be saved by the Ark, and then made it back to the Americas again. The origins of humans in the New World was a similar problem, as they are not mentioned in Scripture. Hale argued that the population of the New World was entirely a post-Flood phenomenon – after all, there were about 4000 years to work with since the Flood – but still, getting across the oceans was a problem. Hale, taking his clue from the work of John Ray and other writers on the history of the Earth, proposed that the places of land and sea were different in the past, and that perhaps long promontories arose, as sea levels oscillated, so that animals could pass from continent to continent, and peoples as well, possibly moving from Asia to North America.

Hale’s book rarely figures in histories of anthropological thought, but it should. He did better than most of his contemporaries at trying to reconcile Scripture with the new data beginning to pour in about the distribution of life on Earth, and recent discoveries about the geological history of the Earth. We cannot really fault him for refusing to abandon his orthodox religious beliefs, since the evidence was not yet good enough for that, and would not be for another century.

Hale wrote one other book on a scientific subject, Difficiles Nugae, or, Observations Touching the Torricellian Experiment (1674), in which he took issue with Robert Boyle’s interpretations of the result of his work with vacuum pumps. We have this work in our collections as well, and we will take a look at it on a suitable future occasion.

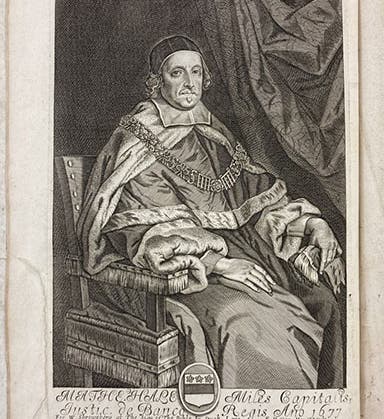

There is an oil portrait of Hale, by John Michael Wright, in the Government Art Collection of the U.K., which you can see here. We prefer to use for our first image an engraving made from that portrait and included as a frontispiece in our copy of The Primitive Origination of Mankind.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.