Scientist of the Day - Matthias Schleiden

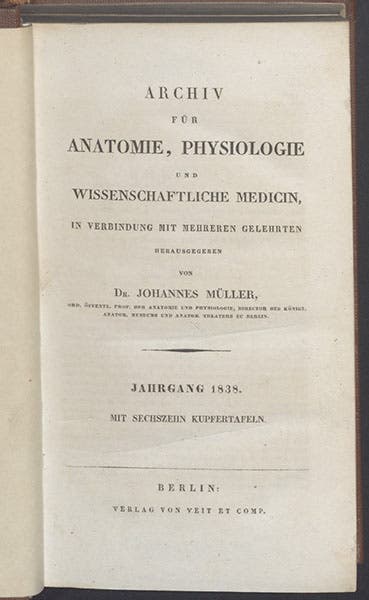

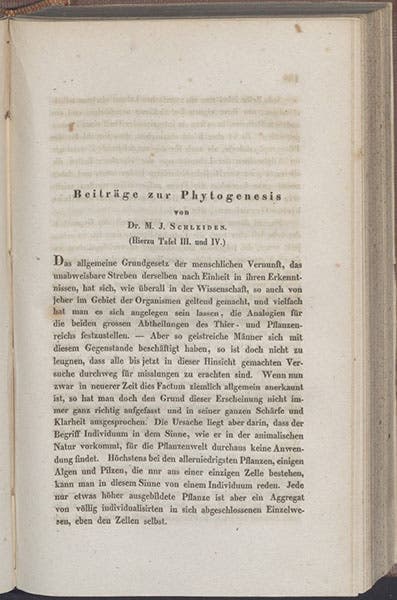

Matthias Jakob Schleiden, a German botanist and microscopist, was born Apr. 5, 1804. Most people vaguely remember "Schleiden and Schwann" from their high-school biology course, where one briefly encountered them right after learning that Robert Hooke coined the word “cell” (you might have been taught that Hooke discovered the cell, but that is not quite the same thing). As to Schleiden and Swann, you probably learned that Schleiden, the botanist, and Theodor Swann, the animal anatomist, discovered that the cell is the fundamental unit of all living things. As is often the case, the truth is not quite so simple. Schleiden did publish a paper in 1838, called "Beiträge zur Phytogenesis" (“Contributions to studies on the origin of plants”). It appeared in a journal with the formal title, Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medizin, which is often referred to as Müller's Archiv, after the editor, Johannes Müller, who just happened to be Schleiden's teacher in Berlin.

In his short article, Schleiden did state that the cell is the fundamental unit of plant structure; i.e., all plants are made of cells. He was not, however, the first to do so, being preceded by, among others, the Czech biologist Jan Purkyně and his pupil Gabriel Valentin. Morever, Schleiden did NOT argue that every cell is produced by the division of another cell, which is a basic tenet of modern cell theory. Rather, he thought that cells were generated from some kind of protoplasm by an entity he called a "cytoblast," which was in fact a cell nucleus, but which Schleiden saw as a "cell generator", which is what cytoblast means. This theory of cell genesis was quite erroneous and was not soundly based on observation. However, Schleiden’s version of the cell theory was taken up by Schwann,, who had independently come to the conclusion that all animal organisms are composed of cells. Schwann published a much more substantive work in 1839, a book called Mikroskopische Untersuchungen, in which he praised Schleiden's work and accepted his cytoblast theory. We wrote a post on Schwann in 2016.

And then, as if to sanction the union of Schleiden and Schwann, an Englishman, Henry Smith, translated Schwann's book and published it in 1847, under the auspices of a new publication sponsor, the recently founded Sydenham Society. Smith also translated Schleiden's paper and tacked it on at the end. The work had the title: Microscopical Researches into the Accordance in the Structure and Growth of Animals and Plants. And it has been Schleiden and Schwann ever since. Cell biologists such as Robert Remak, a Polish Jew who did indeed argue, beginning in 1841, that every cell is the result of the division of other cells, and who was quite critical of the erroneous Schleiden-Schwann theory of cell genesis, are hardly mentioned in English textbooks, even today.

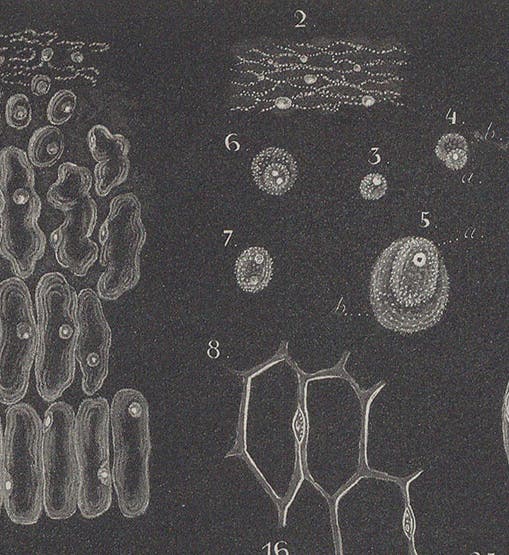

Nevertheless, nearly every biology class that visits our history of science collection wants to see Hooke, and Schleiden-Schwann, and we can display all of their works. With respect to Schleiden, what you would see is what we show you today, the journal in which Schleiden’s 1838 paper appeared, the paper itself, a detail of one of the two plates (the other is not nearly so handsome), and the translation of 1847 that put Schleiden and Schwann on the English-speaking map. There is nothing wrong with looking at these papers and appreciating Schleiden's work – he was a good microscopist and plant cytologist. But it would be nice if biology teachers would also ask to see the works of Purkyně, Valentin, and Remak. It would provide their classes with a much more complete picture of the origins of cell theory.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.