Scientist of the Day - Max Born

Max Born, a German physicist, was born Dec. 11, 1882. Of all the physicists who played an important role in the quantum revolution of the 1920s, Born is the least known to the educated public – many have heard of Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr, and Erwin Schrödinger, but Born's name rarely rings a bell. His contributions however, were major, and he was a close friend and regular correspondent of Albert Einstein to boot. Born really deserved to share in the Nobel Prize of 1932, as even the recipient (Heisenberg) freely admitted.

Born was born in Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland); his family was Jewish. He studied at Breslau, Heidelberg, Zurich, Berlin (where he met Einstein in 1915), even Cambridge, before settling down as a professor of physics at Göttingen, where he would teach from 1921 to 1933. One of his better students was young Werner Heisenberg, an avid mountain-climber who happened to be brilliant. He completed his Habilitation degree under Born in 1924 and stayed on as a Privatedozent – an independent scholar.

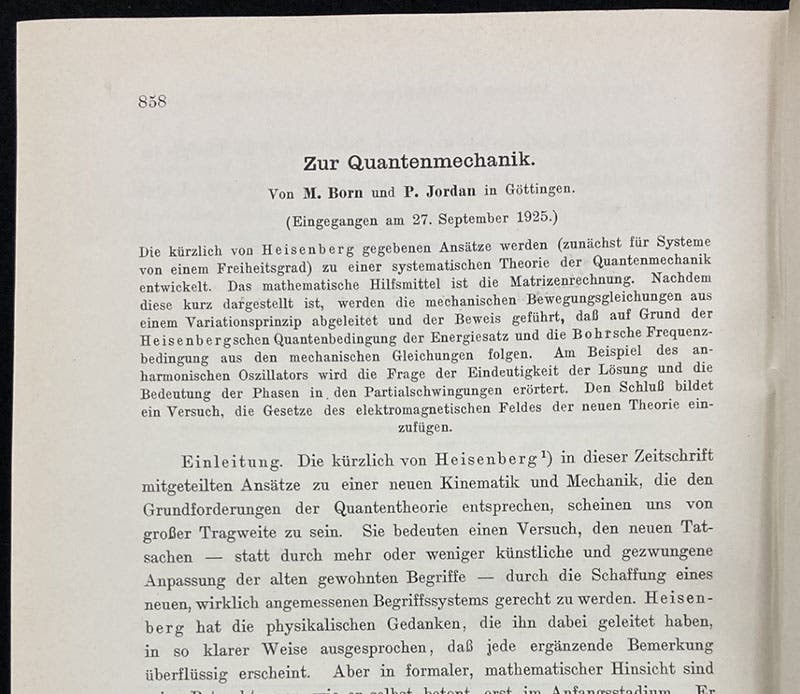

After spending some time with Niels Bohr in Copenhagen, Heisenberg wrote a paper in 1925 in which he proposed a system of quantum mechanics that would describe the world of the atom according to the quantum theory of Max Planck. One of the features of his mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics was that the multiplication of quantities did not commute, a fancy way of saying that “a x b” did not necessarily equal “b x a”. When Born read the paper before sending it off for publication, he noted that the non-commutativity of multiplication was a feature of a branch of mathematics called matrix algebra, and that if you substituted matrix algebra for Heisenberg’s equations, one crated a much more powerful quantum mechanics. Heisenberg at the time had no idea what matrix algebra was. Born and his assistant Pascual Jordan published their version of Heisenberg’s quantum mechanics just two month after Heisenberg’s original paper was published (second image). Before the year was out, all three published a joint paper setting forth the new matrix quantum mechanics.

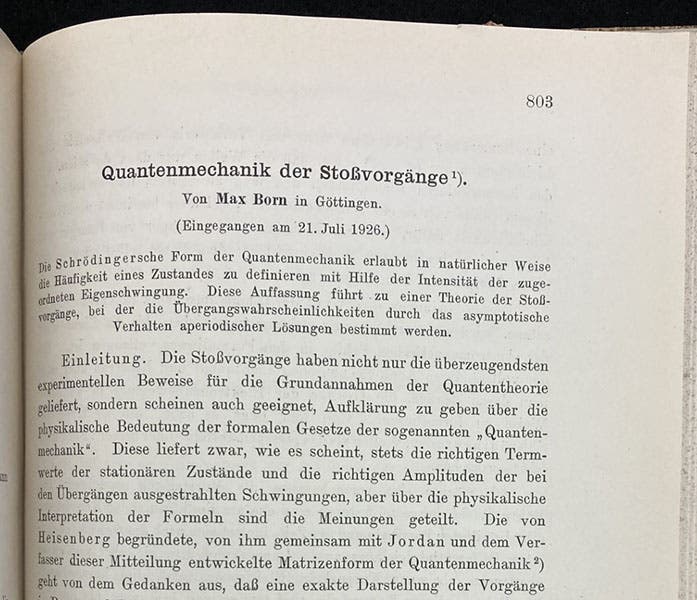

Both Heisenberg and Born were stunned when, in early 1926, Erwin Schrödinger, then in Zurich, independently published a paper that also presented a system of quantum mechanics, but an entirely different one – this one described particles as waves, using what were called wave equations. It was Born who showed that the two systems – matrix mechanics and wave mechanics – were equivalent and gave the same predictions. But the big question raised by Schrödinger’s wave equations was: what exactly do they describe? Many physicists tried to relate wave equations to physical reality, but Born's proposal, made in two papers published in 1926, was the most ingenious and thought-provoking (third image). Born proposed a statistical solution; he suggested that the wave equation for a particle gives the probability that the particle will be found in a certain state or at a certain location. You could not know exactly where a particle is, but you could know the odds of finding it in one place or another.

Born was quite pleased with his probabilistic interpretation of wave mechanics, and he described it in a letter to Einstein in November of 1926. Born was disappointed when Einstein would have none of it. In his December reply, Einstein declared a lack of faith that quantum mechanics describes physical reality. It does not, Einstein ventured "bring us any closer to the secret of the 'Old One'.” And Einstein concluded, in what might be his most famous quotation with respect to quantum mechanics: "At any rate, I am convinced that He does not roll dice."

Einstein nominated both Heisenberg and Born for the Nobel Prize for the foundation of quantum mechanics (a generous act on Einstein’s part, since he wanted nothing to do with quantum mechanics), but when the prize for 1932 was awarded (in 1933), the only recipient was Heisenberg. Born never complained, but he must have been hurt by being left out. Born, however, had more pressing problems at the time, as Hitler in 1933 ordered all Jews removed from professorships at German universities. Born resigned from Göttingen and emigrated to Cambridge, and then to Edinburgh, where he taught until his retirement in 1953, after which he returned to Germany. He did receive the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1954 (shared with Walter Bothe) for his statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics, and I am sure he was happy to receive it, but he was 72 years old at the time, and it is likely that he wondered why it had taken 28 years for his work to be recognized. Many others continue to wonder about that.

Born died on Jan. 5, 1970, and was laid to rest in Stadtfriedhof Cemetery in Göttingen; there is a simple headstone there (fourth image). No fewer than 8 Nobel prize winners are buried at Stadtfriedhof, including Max Planck, Otto Hahn, and Max von Laue.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.