Scientist of the Day - Maximilian Perty

Josef Anton Maximilian Perty, a German naturalist, died Aug. 8, 1884, at the age of 79. Born in Bavaria, he was educated in Munich, and early in his career he worked at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences on insects, in particular, on those brought back by Johann von Spix and Karl von Martius from Brazil. In 1834, Perty secured a professorship at the new University of Bern in Switzerland, where he spent the next 42 years, before his retirement.

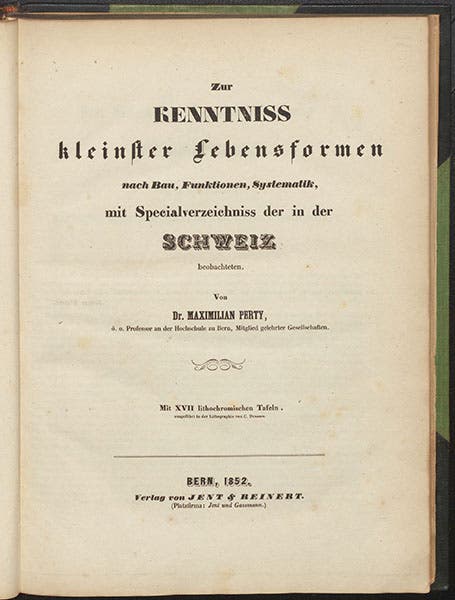

Perty published a variety of works on arthropods and other invertebrates, but we have only one of his books in our library. Fortunately, it is a beauty. The short title, in German, is Zur Kenntniss kleinster Lebensformen, which translates (now including the subtitle) to: On Knowledge of the Smallest Forms of Life: According to Structure, Functions, Systematics, with a Special Index of Those Observed in Switzerland. It was published in Bern in 1852, and is a modest-sized folio. The book is an exhaustive treatment of what we would call protozoa, and back then were often referred to as zoophytes or infusoria, or, as Perty calls them, "kleinster Lebensformen."

Protozoa became an object of study when microscopes got good enough to reveal the details of their existence, which would seem to have been about 1835. The first comprehensive book on protozoa was Georg Ehrenberg’s Die Infusionsthierchen (1838), followed closely by Felix Dujardin's Histoire naturelle des zoophytes (1841). Ehrenberg began the tradition of supplementing his specialized text with glorious hand-colored illustrations that made infusoria attractive to just about everyone. We have featured both Ehrenberg and Dujardin as previous Scientists of the Day, where you may behold the visual evidence for my praise.

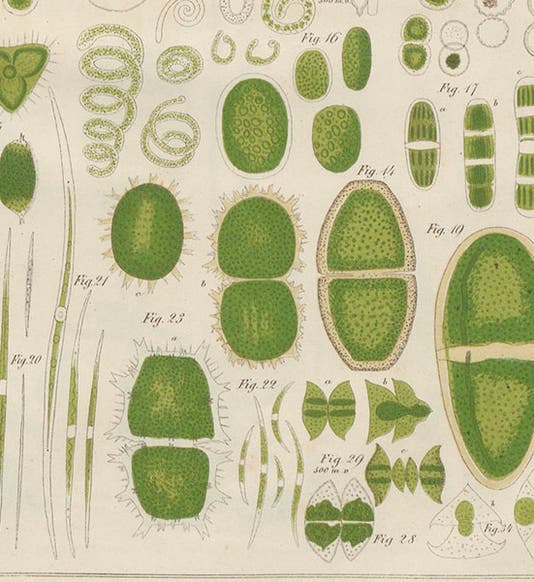

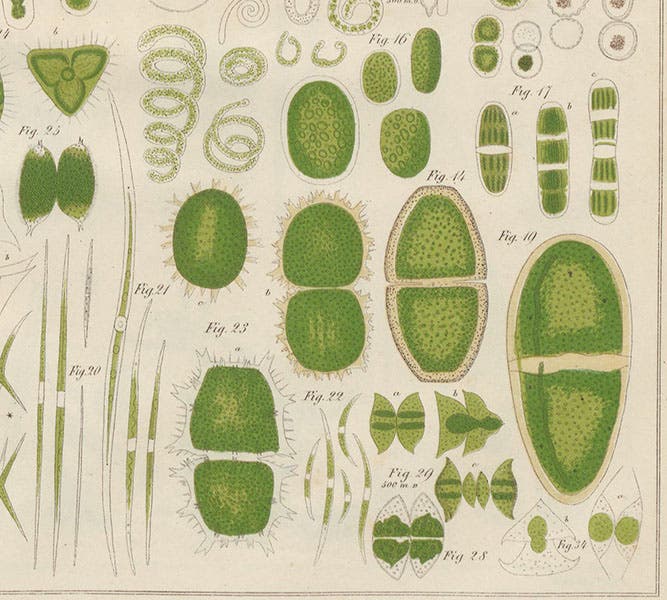

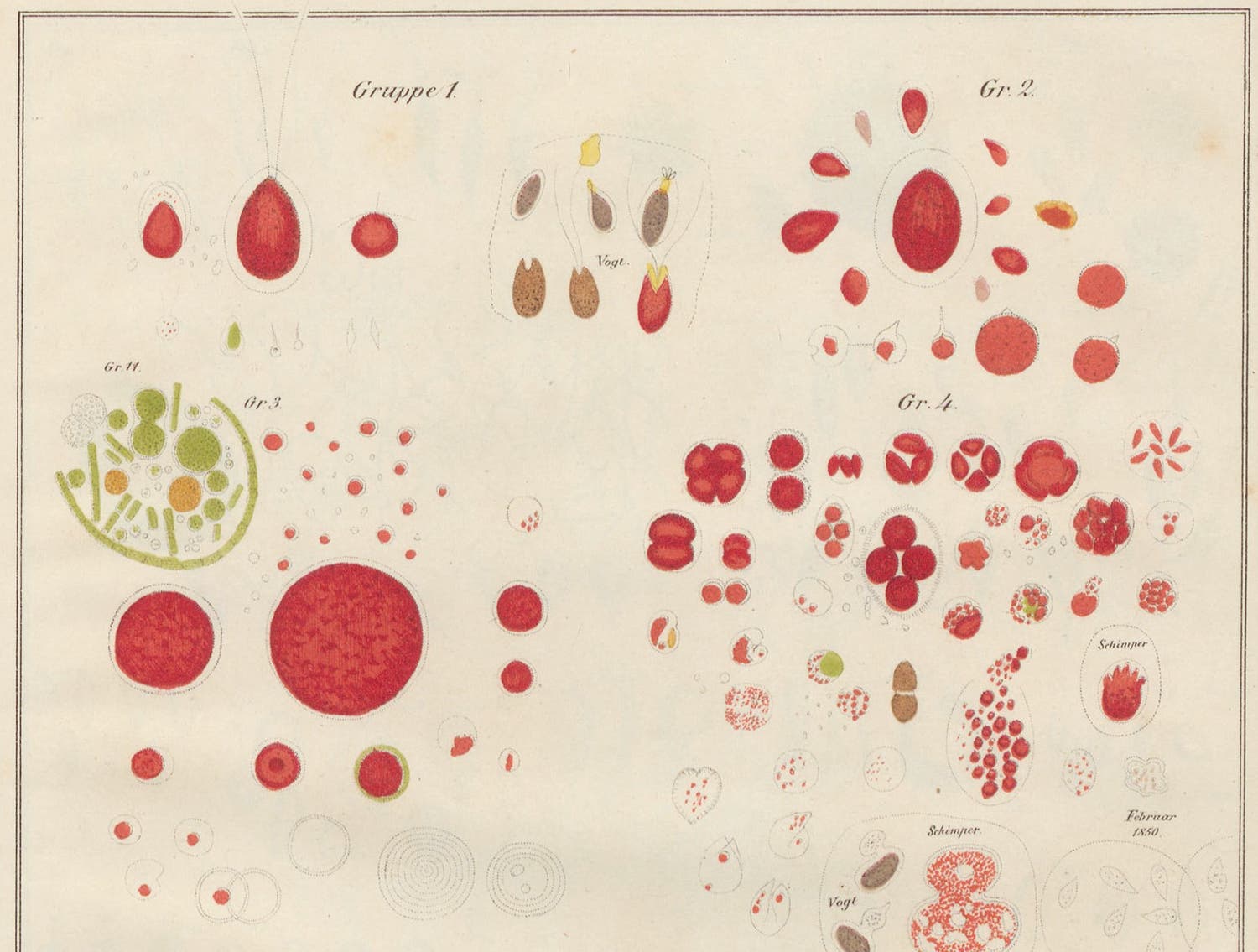

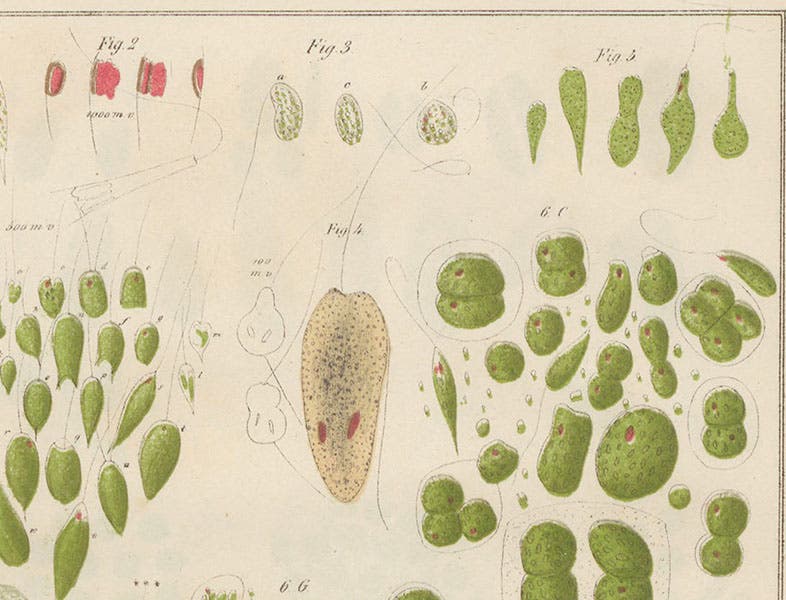

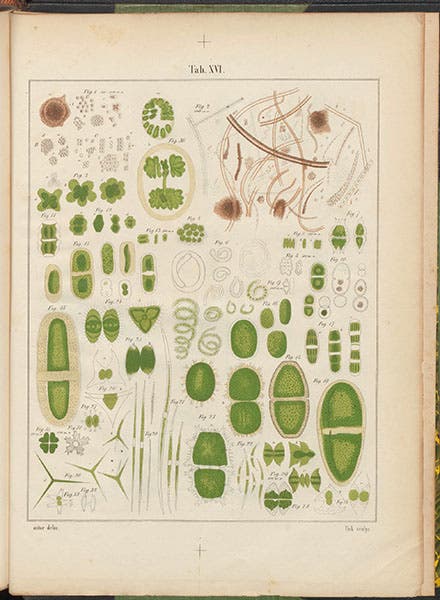

Perty continued this tradition, and although the 17 hand-colored engravings in his work do not elicit quite the oohs and aahs of Ehrenberg's book, they are still wonderfully colorful, and, experts say, accurate in their details. As I explained when I wrote about Dujardin and Ehrenberg, I know very little about protozoa or the history of protozoology, so I cannot do much here but show you some of the plates, one in its entirety (sixth image), with the others enlarged so you can see the tiny "animalcules," as Leeuwenhoek used to call them. I was intrigued by plate 13, with depictions of red algae (fourth image). Perty tells us that these represent the organisms of the “rothen Schnees” – the “red snow” of alpine and polar regions. This struck a chord, because we have one of the first illustrations of "red snow", in a book by the polar explorer John Ross; you may see his large folding plate of a long bank of red snow as the last image in our post on Ross, as well as in our exhibition catalog, Ice: A Victorian Romance.

I looked up some of Perty's described species in several of the online marine databases (of which there are many), and found that Perty did his job well; many of the species he named are still intact. For example, on plate 10, at the top right, he pictured some organisms that he named Eutreptia viridis (fifth image). These are tiny algae with a pair of flagellae to whip them about. If you look Eutreptia viridis up in Algaebase, you find this record, which traces its description back to Perty. There are many such examples, but I am sure one will suffice to make the point that Perty made valuable contributions to protozoology.

Our copy of Perty’s book carries the bookplate of Frank Patrick on the inside front cover. Patrick was a Kansas City banker and amateur naturalist and microscopist who put together an impressive library on microscopy and protozoology. He conveyed his love of the microscopic world to his daughter Ruth, who became one of the world's foremost experts in limnology and ecology. When Ruth Patrick died in 2013 (at the age of 105!), she left most of her library, which included her father's books, to the Linda Hall Library. We are very happy to have them.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.