Scientist of the Day - Orazio Grassi

Orazio Grassi, an Italian Jesuit mathematician and astronomer, was born May 1, 1583. He studied at the Collegio Romano under Christoph Clavius and his successor, Christoph Grienberger, the latter one of the more liberal and forward-looking Jesuit astronomers. Grassi spent some time teaching in Genoa, and then returned to Rome in 1616, where he would teach both mathematics and architecture. He was by all accounts (except Galileo's) a bright, affable, respectful fellow and a credit to the Society of Jesus.

In the fall of 1618, three comets appeared in the skies, the first in late August, the third and brightest in late November. Four lectures were given about the comets at the Roman College, by a theologian, a philosopher, a professor of rhetoric, and a mathematician, and Grassi gave the last. He infringed on the turf of the philosopher and observed that the comet exhibited no parallax and must therefore be higher than the Moon, which made it a celestial object (Aristotle had maintained that comets are sublunary, and are terrestrial in origin). Grassi leaned instead in the cosmological direction of Tycho Brahe, who placed all the planets, including comets, in orbit around the Sun, which then circled an immobile Earth. Many Jesuits were coming to embrace the Tychonic cosmology, which avoided the interdictions of 1616 against Copernicus and his heliocentric cosmology.

![Text of the prologue, where Grassi says (line 5-6), “Soli igitur Cometae supererant, lynceis hisce oculis spectandi” (“Thus only comets remain to be observed by Lincean eyes”), referring to the Academy of the Lynx and its most prominent member, Galileo; page 4 in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/843fdf66-7458-413c-8929-2d860810e7ea/Grassi%2013.jpg?w=800&h=441&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Text of the prologue, where Grassi says (line 5-6), “Soli igitur Cometae supererant, lynceis hisce oculis spectandi” (“Thus only comets remain to be observed by Lincean eyes”), referring to the Academy of the Lynx and its most prominent member, Galileo; page 4 in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)

Grassi's lecture was published early in 1619, with the title, De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica publice habita in Collegio Romano Societatis Iesu (On the Three Comets of 1618, an Astronomical Disputation Held Publicly at the Roman College of the Society of Jesus). Authorship was attributed to "one of the fathers of that society," but it was no secret that it was Grassi's lecture that was being printed. De tribus cometis is a very scarce bit of Galileiana, and the library was fortunate to be able to acquire a copy earlier this year from Sophia Rare Books in Copenhagen. When we first wrote a post on Grassi in 2020, we had to show the title page of another copy. Now we can show the title page of our own copy, as well as some of ts contents.

By the standards of the day, Grassi's little treatise was progressive and insightful, even a little daring in its dismissal of Aristotelian views on comets. There was only one brief but clever dig at Galileo, in the prologue, where Grassi extols all we have learned recently about new moons around planets and spots on the Sun, then comments that "only comets have escaped lynx eyes," referring to the Lincean Society (Academy of the Lynx). of which Galileo was a proud member (third image).

So neither Grassi nor Grienberger was prepared for the reaction from up north, from Florence, Galileo's home, after De tribus cometis was published. Galileo had been sick and bedridden all Fall, so it is doubtful that he saw any of the three comets himself. But he was still smarting from the events of 1616, when Copernicus' De revolutionibus had been placed on the Index, heliocentrism had been declared heretical, and Galileo had been personally admonished by Cardinal Bellarmine not to defend the Copernican system. And Galileo was not partial to Jesuit astronomers, even his admirer Grienberger, especially after his run-in with the Jesuit Christoph Scheiner in the controversy on sunspots of 1612-13.

So Galileo hauled himself from his sickbed and penned a response to De tribus cometis that was a vituperative attack on Grassi’s competence as a natural philosopher and mathematician. It was called Discorso delle comete (1619), and in it, Galileo declared that comets showed no parallax because they are not physical objects, but exhalations from the Earth. Rather than publish this attack under his own name, he published the Discorso under the name of a pupil, Mario Guiducci. The Jesuits in Rome were more than shocked, they were outraged, and they knew it was not Guiducci’s handiwork, but Galileo’s. The dust never settled from the Discorso, and Galileo’s relationship with the Jesuits, and the Church as a whole, was forever changed.

Our library acquired the Discorso last year from New York City bookseller Jonathan Hill, and since it deserves its own place in the Sun, we will defer further discussion until June 9. But we can mention that the Discorso provoked its own reply from Grassi, who had been transformed by the Discorso from Mr. Agreeable to Father Ferocious. He called his new book Libra astronomica (Astronomical Balance), and it was nearly as intemperate a treatise as Galileo’s (Guiducci’s) Discorso. We wrote an entire post on the Libra in 2020, where you may follow the story further, up through Galileo’s Il saggiatore (The Assayer, 1623), the final installment in the saga. At the time I wrote, the first two books of the tetralogy on comets were not in our collections. Now we have them all.

![Path of the third comet of 1618, first observed on Nov. 26 in Libra, then passing through Bootes and Ursa major, also showing observations made at the Roman College and at other Jesuit colleges in Parma and Antwerp, detail of right half of large folding engraved plate, in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/7ae9c44b-72d7-404f-957e-fea161844999/Grassi%2017.jpg?w=477&h=601&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Path of the third comet of 1618, first observed on Nov. 26 in Libra, then passing through Bootes and Ursa major, also showing observations made at the Roman College and at other Jesuit colleges in Parma and Antwerp, detail of right half of large folding engraved plate, in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)

I thought I might make a final comment about the engraved star map, or set of star maps, in De tribus cometis. Grassi, being a mathematician, provided daily positions in the text for the comets, especially the third one, and he referred to meridians and arcs with pairs of letters such as KN and MP, as if referring to a geometrical diagram. There are no diagrams in the text, but there is an elegant engraving bound in, with maps of the changing position of the comets (fourth image, with details in first, fifth, sixth and seventh images). It is beautifully drawn and engraved – too fine, really, for this treatise – but it is not signed, and Grassi never explicitly refers to it. But it was clearly made for this book, as it shows the paths of all three comets, and the identifying letters, labels, and dates correspond exactly with Grassi’s text.

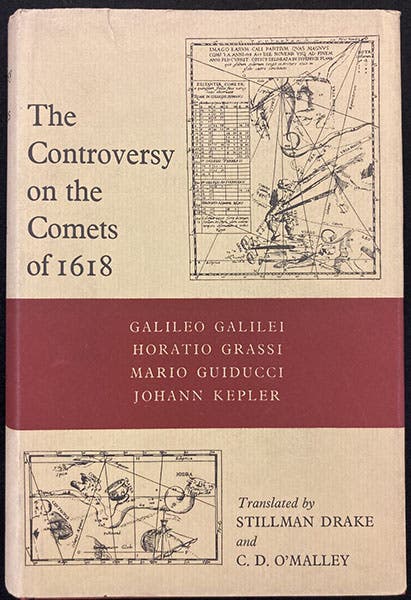

Dust jacket, The Controversy on the Comets of 1661, ed. by Stillman Dake and C. D. O’Malley (Univ. of Pennsylvania Pess, 1960), with two details from the engraved plate in De tribus cometis, by Orazio Grassi, 1619 (Author’s copy)

When translations of all four works were published in 1960 (as The Controversy on the Comets of 1661, ed. by Stillman Drake and C. D. O’Malley), two details from the map were used on the dust jacket, but the folding map was reduced to postcard size and presented as a frontispiece, which hardly did justice to the engraving (eighth image). It would be nice to know more about this map. Since Grienberger published a star atlas of his own in 1612 (see our post on Grienberger), I am guessing he was somehow involved.

There is no portrait of Orazio Grassi. And unlike our subject yesterday, David Thompson, Grassi doesn’t even have a postage stamp with an imaginary portrait. I wish we had something that projected his persona, other than the thin pamphlet with the lovely engraving that is now in our collections (ninth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![The path of the third comet of 1618 from Libra to Bootes, Nov. 26 – Dec. 20, detail of bottom right, large folding engraved plate, in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/7fb58186-1a8b-4397-93e4-180a3606477b/Grassi%2011.jpg?w=534&h=582&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![The path of the third comet of 1618 from Libra to Bootes, Nov. 26 – Dec. 20, detail of bottom right, large folding engraved plate, in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/7fb58186-1a8b-4397-93e4-180a3606477b/Grassi%2011.jpg?w=773&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Title page, De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/6c4f0f67-04ea-4a6c-aa76-5dc90163661b/Grassi%2012.jpg?w=454&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Large folding map of the paths of the three comets of 1618 against the stars, engraving, unsigned, in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3327b5ff-5f6d-454b-b927-831af029d137/Grassi%2014.jpg?w=800&h=574&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Path of the first comet of 1618, first observed on Aug. 29, in Ursa major, detail of upper left of large folding engraved plate, in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/2de648d6-a2f3-4f1a-b953-f74bcc9b0702/Grassi%2015.jpg?w=800&h=462&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Path of the second comet of 1618, first observed on Nov. 18, in Centaurus, detail of lower left of large folding engraved plate, in De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/c5429648-9405-4144-8395-ed5a09fc13e6/Grassi%2016..jpg?w=800&h=508&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Limp vellum binding, De tribus cometis anni M.DC.XVIII: Disputatio astronomica, by [Orazio Grassi], 1619 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/01fc8407-b781-479e-bfbc-c24d643494df/Grassi%2019.jpg?w=449&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)