Scientist of the Day - Palomar 200-inch Pyrex Disc

When the 100-inch Hooker telescope went into operation in 1917 on Mount Wilson in Pasadena, California, it was the largest light-gathering instrument in the world. But the guiding hand behind the 100-inch reflector, George Ellery Hale, was already thinking about an even bigger reflector, and in 1928, he announced his intent to build a reflecting telescope with a mirror 200 inches in diameter, which would give it 4 times the light gathering capability of the Moun. Wilson telescope. The mirror would be formed by grinding and polishing a parabolic concavity into a 200-inch blank disc of glass. The biggest obstacle would be the casting of that blank

First attempted cast of a 200-inch Pyrex disc for Palomar, a failure, on display at the Corning Museum of Glass, view from second floor, photograph, 2025 (author’s photo)

Hale spent years negotiating with General Electric, who promised Hale that they could provide a 200-inch blank of fused quartz, and who ate up some $600,000 of Rockefeller Foundation money attempting to do so. But they never produced a single useable blank of any size, and in 1932, Hale showed GE the door and turned to the Corning Glass Works in Corning, New York.

First attempted cast of a 200-inch Pyrex disc for Palomar, a failure, on display at the Corning Museum of Glass, view from first floor, photograph, 2025 (author’s photo)

For some years, Corning had been turning out objects made of Pyrex, a borosilicate glass that shows almost no tendency to expand or contract when it gets hot or cold. This property would be invaluable for a telescope mirror, because glass mirrors have a tendency to contract and change shape when the observatory dome is opened and the cool outside air comes in, and if the mirror is large, it might take all night to stabilize and become useful only when the sun is about to come up, which is to say, it would not be very useful at all. A Pyrex mirror that exhibited no thermal expansion might be just the solution. The Corning plant had never made anything this large out of Pyrex glass. It would require a special casting facility, and a mammoth annealing oven, and many skills and techniques that no one had yet acquired. But Corning was eager to tackle the challenge, and Hale was willing to take the chance.

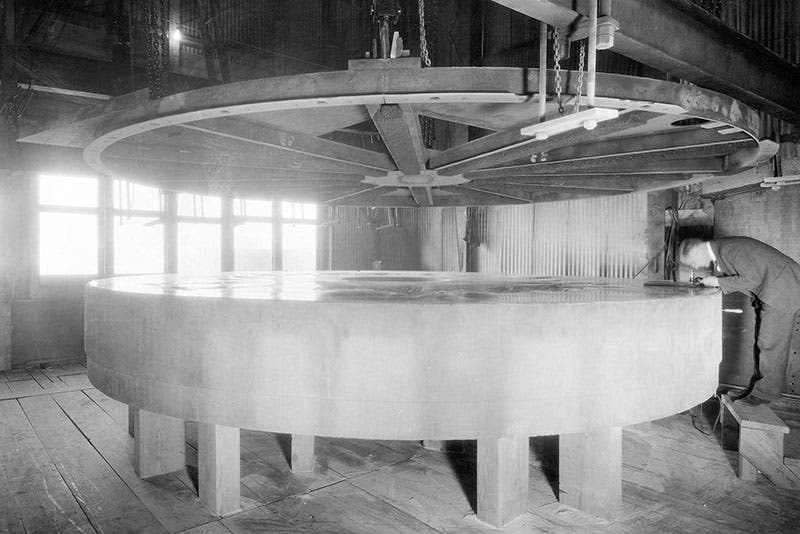

It became clear early on that a 200-inch Pyrex blank could not be solid glass. For structural reasons the disc would have to be almost two feet thick and would weigh about 40 tons, making it much too heavy to mount in a telescope; it would sag if you stood it up on its edge. So Corning decided to "honeycomb" the disc, to put over a hundred core inserts in the bottom of the mold to reduce the amount of glass needed. The back would then look rather like a Belgian waffle, although the front would be smooth, ready to be ground to a parabolic concave shape. The honeycombing would reduce the weight by about half.

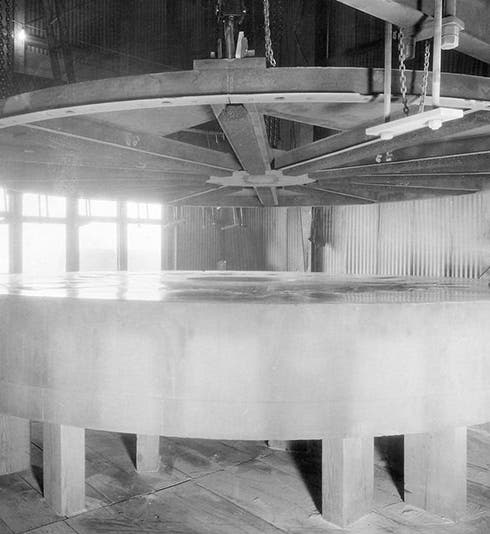

Corning produced some smaller blank discs to learn what they could and could not do, and then they decided to tackle the big one. Word of the project got out, and thousands of journalists showed up in little Corning on Mar. 25, 1934, the day of the pour. The country was in the depths of the Depression, and news that could distract or inspire was eagerly sought out. The pour took all day, as enormous ladles of molten borosilicate glass were conveyed on overhead rails to the enclosure housing the gigantic mold. Everything seemed to be going well, until a worker noticed that something had bobbed to the surface of the molten disc. It was one of the core inserts, which had come loose from its mooring, and it was soon followed by about 20 others. The blank was ruined. The men in charge decided to finish the pour anyway, and to go ahead and anneal the disc, since the annealing process was as much a mystery for a large glass disc as was everything else, and they might well learn something that would come in handy if they ever got a good disc. For posterity, i.e., us, this turned out to be an excellent idea, for that rejected disc is on display at the Corning Museum of Glass, where it looks rather splendid, for a failure. I saw it last spring, where it has been ingeniously mounted between two floors of the museum (second and third images). If you look closely, you can see where some of the cells filled in with glass when the cores broke loose and floated to the surface (which is on the other side; you are looking at the back of the disc).

While everyone waited for another go at casting a disc, the site selection committee, convinced that a 200-inch disc was going to be produced, finally decided on a location for the 200-inch telescope – Palomar Mountain, about 115 miles SE of Pasadena, and 60 miles NNE of San Diego, at a site just over 6000 feet above sea level.

On Dec. 2, 1934, Corning tried again to cast a disc. For the second attempt, the core inserts were better secured, techniques of stirring and delivering the molten glass were improved, and this time the pour was successful. When the disc was cool enough, it was moved to the annealing oven, where the disc temperature was lowered a little less than 1 degree per day for just under a year, after which it was left to cool the rest of the way on its own. The year in the annealer also led to a year of considerable anxiety for those in charge, since there was no way to check if there were any cracks in the disc until it was removed from the oven. To complicate matters, there was a flood in Corning in the fall of 1935; the disk was never threatened, but the transformers that provided power to the oven were, and they had to be pulled by a crane through a jack-hammered hole in the floor above to save them from being flooded. But the disc came out nearly perfect, except for some surface flaws that would later be ground away (first image).

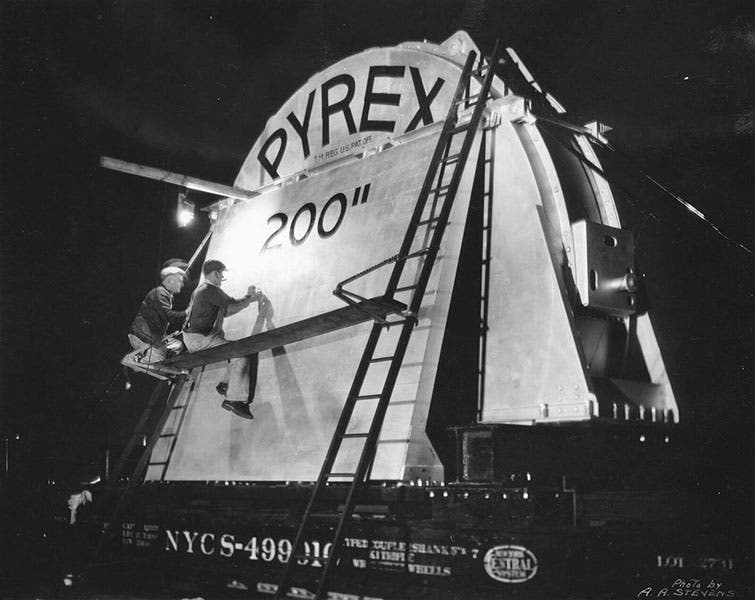

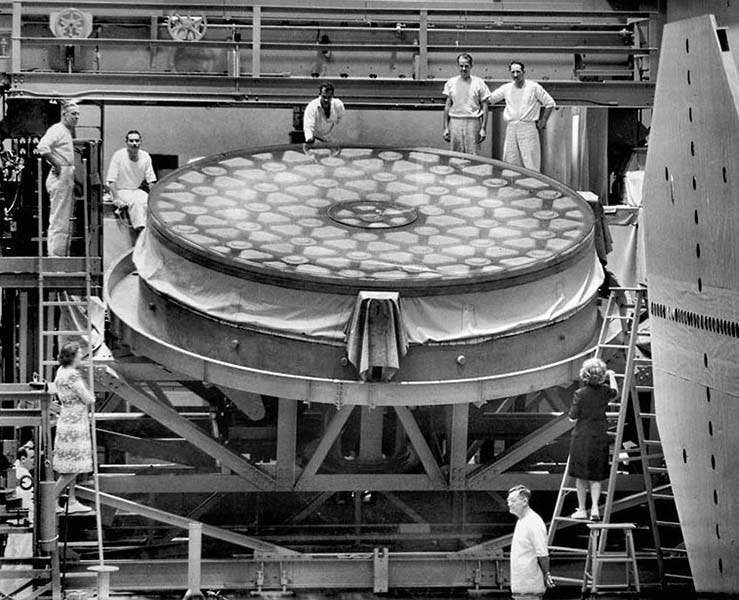

By the spring of 1936, the disc was ready to ship across country to Pasadena. The disc was 16' 8" wide, even without its crate, so it was too large to ship horizontally, and too tall when tipped vertically to go by truck, so Hale settled on a rail journey. He selected a consortium of four railroads who agreed to his terms (25 mph speed limit, no travel at night, 24-hour security), and a special well-car was constructed, so the disc would ride just 5 inches above the rails. Still, it required almost 19 feet of underpass clearance, and it was not easy to lay out a route. The disc’s rail journey developed into a national event, and thousands turned out in every town on the route to see this modern miracle of American ingenuity, even though all you could see was a large steel-swaddled round case, painted white, with the words "Pyrex" and "200 telescope disc" and "Corning Glass works" painted in large black letters on each side. It took just 14 days to cross the country. The disc arrived in Pasadena on Apr. 8, 1936; it was conveyed by truck to the optics laboratory in Pasadena, where it would be ground and figured to shape. Little did anyone suspect that it would sit there for 11 years, thanks to the intervention of World War II. But it would eventually be figured, and we show a photo of the Pyrex disc in 1945, roughly ground to shape, where you can admire the honeycomb structure that shows through (sixth image). By 1948, the finished mirror would be installed in its mount, and by 1949, it would take its first photograph. The instrument that holds the mirror, the Hale telescope, is itself a wonder, and it figured prominently in a separate post on Russell Porter.

If you want to see the first disc, you can go to the Corning Museum, at any time that it is open. If you wish to see the second disc, the one that works for a living, you need to plan your journey. The disc is always there, in the Hale telescope, but you normally cannot see any of the Pyrex. However, every three years or so they remove the mirror and re-silver it. If you arrive at that time, and they let you in, you can see the sides of the Pyrex disc, as well as the shiny paraboloid aluminum surface (last image).

If you go to the Caltech webpage about the history of Palomar, there is a 35-image slide show about the making of the 200-inch disc, which includes several videos, that is very informative, and from which several of our images were taken. Just scroll down about four screens to the fifth image, with a large blue arrow, and click on it. Here is the link.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.