Scientist of the Day - Paolo Uccello

Paolo Uccello, a Florentine painter and mathematician, was born Paolo di Dono near Arezzo in Tuscany around 1397, and died Dec. 10, 1475, in Florence. He is nearly always referred to by his nickname, Uccello, “of the birds,” because of his supposed fondness for drawing birds. He was apprenticed in his late teens to Lorenzo Ghiberti, the noted sculptor then working on the Baptistery doors for the Florentine Cathedral.

The 1420s in Florence was an exciting time to be learning the art of painting. Filippo Brunelleschi had just invented the technique of one-point perspective, and his pupil Masaccio was putting it into practice. Most of the early practitioners and teachers of perspective were humanists, like Leon Battista Alberti, but Uccello was not, and that, I think, is why he appeals to me. He was a Late Gothic painter, meaning he preferred to make his paintings as rich and decorative as possible, and he avoided the classical tendencies of other Florentine painters such as Alberti and Piero della Francesca. And yet he loved the precision of perspective and the way it allowed him to put depth into his paintings. He maintained his Gothic style right up until his last painting, which we are featuring today, The Hunt in the Forest, painted around 1470, when he was 73 years old, and now in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford (first and third images).

The whole idea is whimsical – who would stage a hunt in the woods at night? – but it gave Uccello the opportunity to lay out a deep forest using his perspective skills, and then populate it with horses, dogs, hunters, and deer, all in subdued but compelling nighttime tones. We show a detail as our first image, and the complete painting (which is almost 6 feet wide) as our third image.

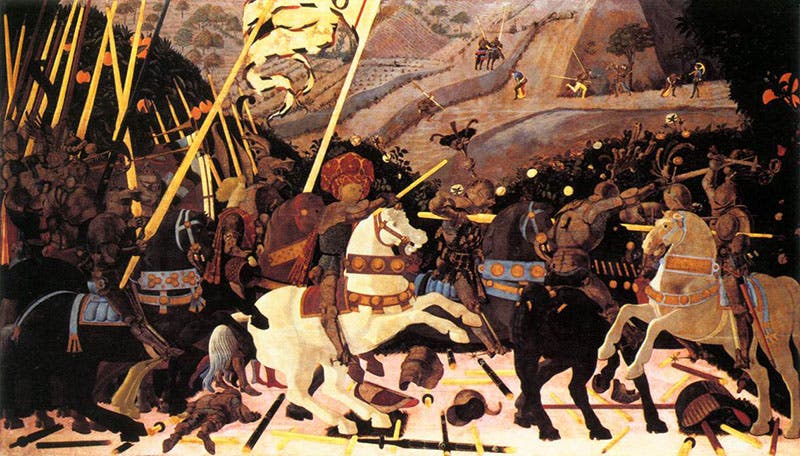

Uccello is much better known for a series of three panels that he did 20 years earlier, known collectively as The Battle of San Romano. The panels were once all together in the Medici Palace in Florence, but now they have found separate homes in the Uffizi, the Louvre, and the National Gallery in London. We show the London panel (fourth image), because it demonstrates Uccello’s playful side. The orthogonals, the lines that recede to the vanishing point, and which in classical perspective painting might be indicated by the tiles of a piazza receding into the distance, are here indicated by the broken lances of the combatants, and by two fallen knights, foreshortened in the direction of the vanishing point.

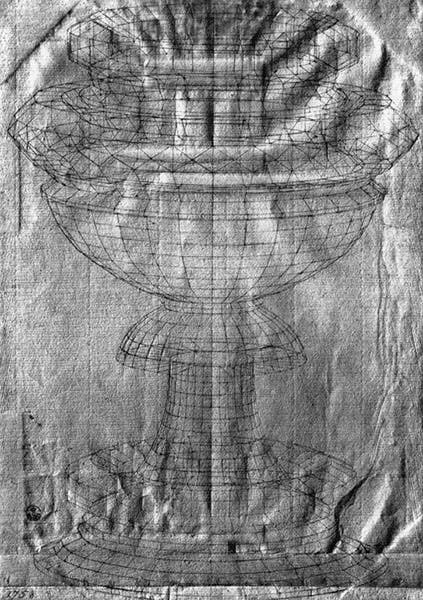

Finally, we show you a sketch by Uccello that demonstrates why perspectivists had to be skilled in mathematics, which pulls them under the rubric of science (fifth image). Uccello’s sketch of a 32-sided chalice is included in nearly every chapter on Renaissance perspective, although this is the only version I have seen that doesn’t edit out all the folds and creases and make it appear more finished than it is. The original pen-and-ink drawing is in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

There is only one portrait of Uccello (second image), and it is part of a large 5-portrait panel in the Louvre, by an unknown master, and called Five Men (since all the subjects are architects, sculptors, or painters, it would be better referred to as Five Artists). I have shown the complete panel in our posts on Brunelleschi, Giotto, and Antonio Manetti. But since the panel was once thought to be by Uccello himself, and thus his portrait a self-portrait, it seems only proper to include the entire painting again here (sixth image). The portraits depict (left to right); Giotto, Uccello, Donatello, Manetti, and Brunelleschi.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.