Scientist of the Day - Pierre Jacotin

Pierre Jacotin, a French topographical engineer and cartographer, was born Apr. 11, 1765. This means he was one of the elder statesmen when, at age 33, he set off with Napoleon and his army to invade Egypt in 1798. Jacotin was one of 151 savants, as they were called, mostly engineers, who went along in order to survey and study the country they expected to conquer, and did.

Jacotin was responsible for producing the first scientifically surveyed map of Egypt. This required a variety of surveying instruments – theodolites, sextants, measuring rods – and unfortunately, most of these were lost when the ship carrying the instruments sank at Alexandria. But Jacotin had replacement instruments made in Cairo and sent his men out with the military expeditions that marched into upper Egypt and the Suez and nearly every other inhabitable locale in Egypt. Many of the young engineers, like Edouard Devilliers du Terrage and Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois, got distracted by the ancient temples at Dendera, Thebes, Philae, and elsewhere, and wanted to survey and measure them instead, but Jacobin managed to collect enough cartographical data for his map.

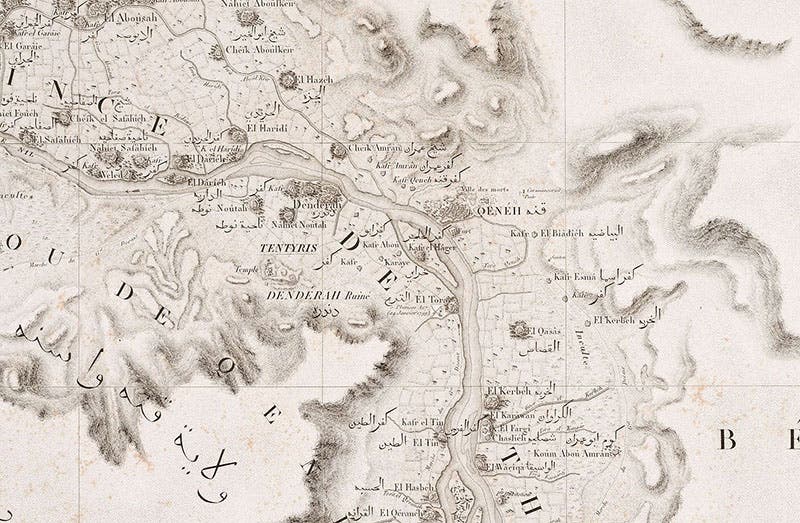

When the savants returned to Paris in 1801, Jacotin set to work. The goal was to produce 1:100,000 scale maps of the inhabited regions of Egypt, which is to say, along the Nile and the coast of the Mediterranean and Red Seas, and a 1:1,000,000 scale map of the entire country. These maps were going to be printed on the largest paper that could then be made, what the French called Grand-Jésus leaves, up to 25 x 50 inches in size. Jacotin had many topographers and 23 engravers at his disposal. Unfortunately, in 1808, Napoleon, now emperor, decided that the new map of Egypt was too valuable to be given away to France's enemies, and declared it a state secret. The other volumes of the Description de l’Égypt began to appear in 1809, but no maps. Jacotin and his cartographers labored on, but with no assurance that their work would ever see the light of day. Even when Napoleon was exiled and the monarchy reinstated, the prohibition stayed in place. It was not until 1828, when Jacotin was now 63 years of age, that the monumental Carte topographique de l’Égypt was finally published, the last volume of the Description de l’Égypt to appear.

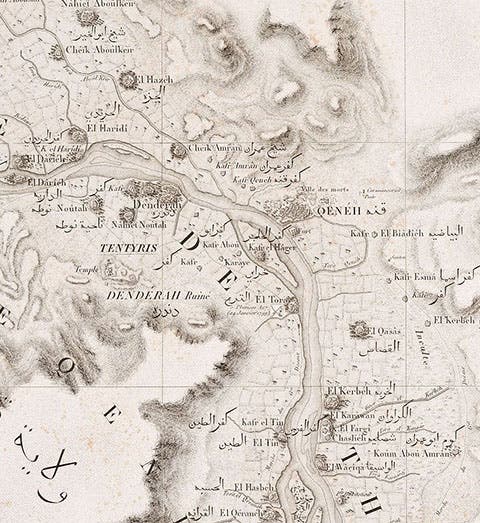

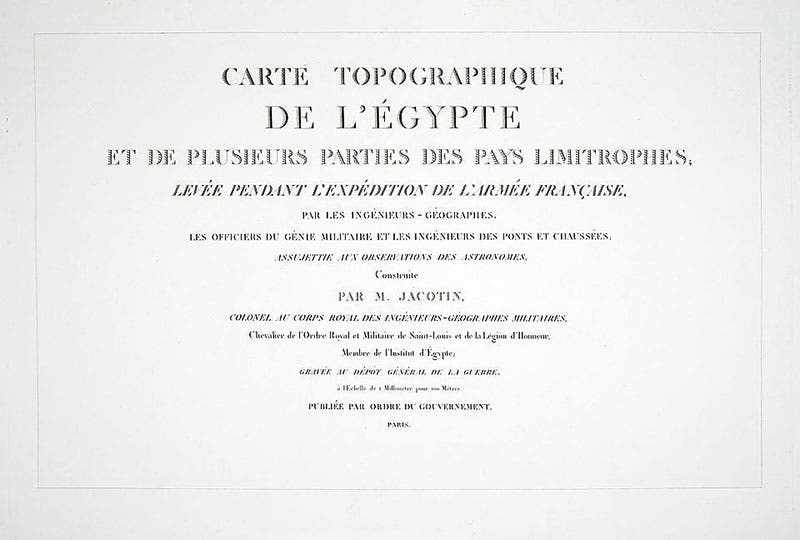

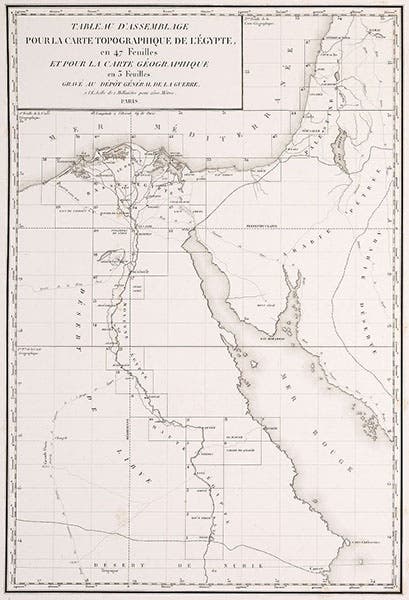

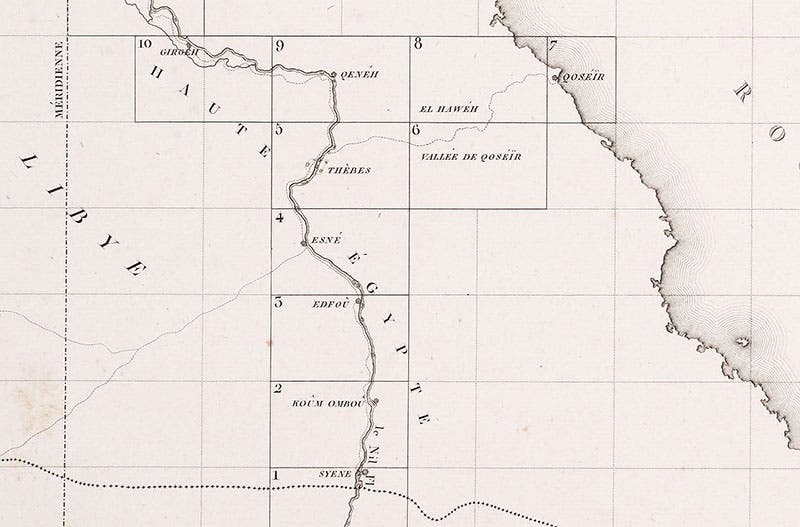

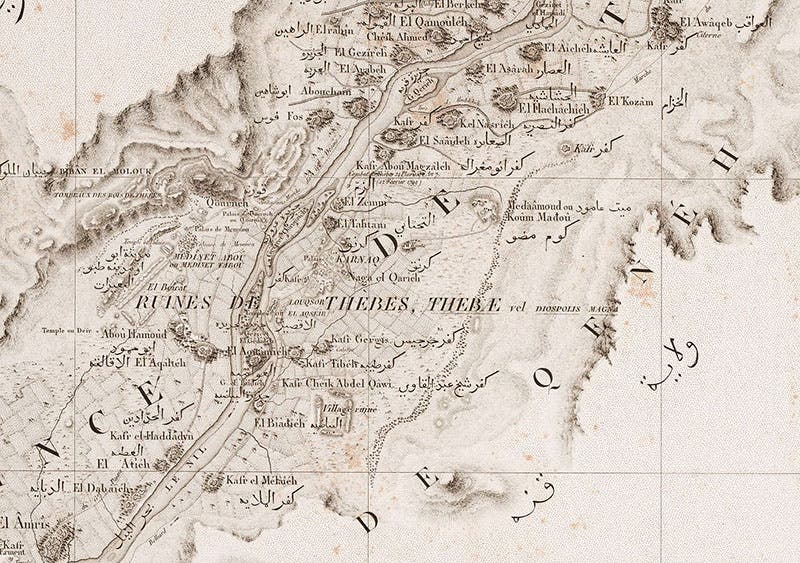

The volume containing the maps is something to behold, and to try to manipulate. Almost five feet long lying down, and three feet wide, it takes two people to retrieve it from the horizontal folio roller-shelves where the plate volumes of our copy of the Description are stored, and it visibly sags in the middle when you carry it to a large table to open it up. Jacotin's name is there on the title page, as Colonel of the Royal Corps of Military Engineer-Geographers (third image). There is an index map at the beginning, showing the areas mapped by the forty-seven 1:100,000 scale maps that follow, plus three sheets that contain the 1:1,000,000 scale map. We show here the index map (fourth image), and a detail of the region along the upper Nile (fifth image) that shows the boundary of map 9, which includes Dendera, where the great stone zodiac was found, and map 5 where the temples at Luxor and Karnak, and the temple of Memnon, are located. We do not have room to reproduce the complete maps 5 and 9, so we show details where you can make out the outlines of the temple at Dendera (first image), and the ruins at Luxor and Karnak in Thebes (sixth image).

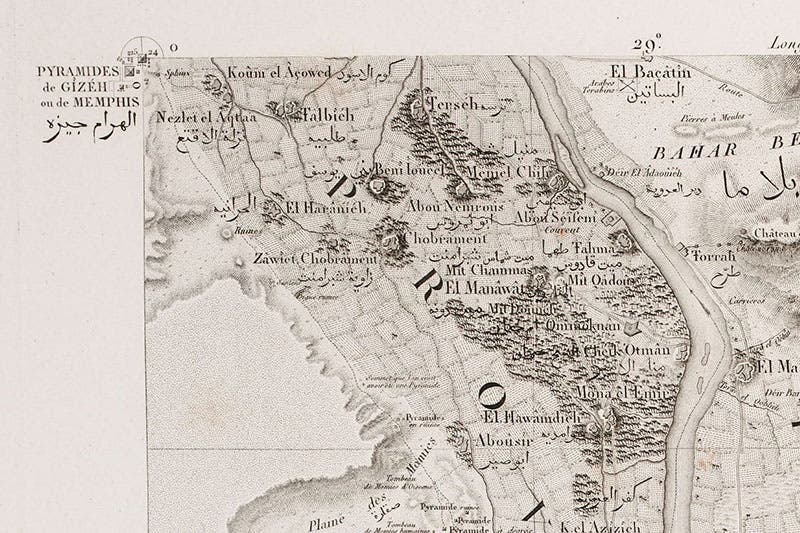

Someone, perhaps Jacotin himself, decided that the coordinates of longitude and latitude for the Egyptian map were to be based on lines that ran through the top of the Great Pyramid at Giza. Thus the four maps that have lines of 0° longitude and latitude as their borders had to be expanded slightly at the relevant four corners to show the location of the pyramids. We show you a detail of map 21, where the Great Pyramid is at upper left, right on the 0,0 point, and the other two pyramids can be seen nearby (seventh image).

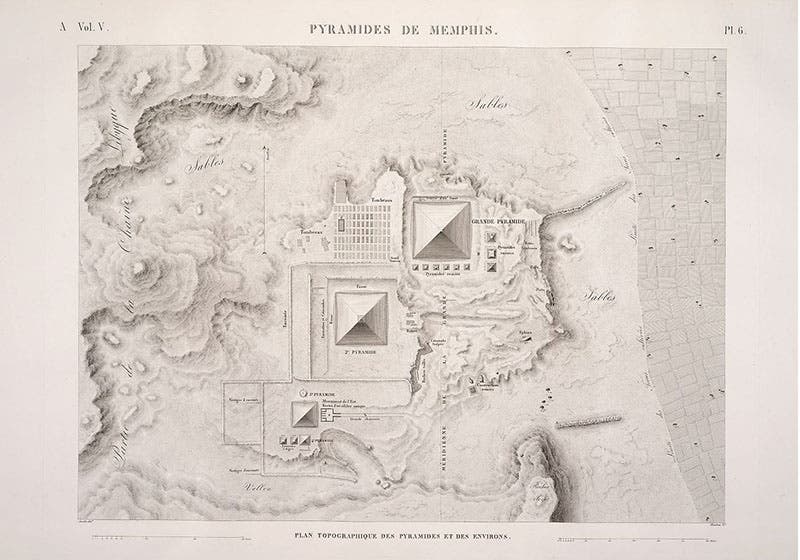

Fortunately for Giza fans, Jacotin was involved in some of the topographic work done at the ancient temple sites, and he signed off on a ground plan of Giza that was published in the fifth and last volume of Antiquities plates (eighth image). Since this was done on Grand-Jésus paper, it is often (as in our set) bound separately, along with all the other super-large plates.

The only portrait of Jacotin known to me is the engraving, based on a sketch by Andre Dutertre that was drawn in Egypt in 1799, and not published until 1830, in Louis Reybaud, Histoire de l’expédition française en Égypte (second image). We have used Dutertre’s portraits many times in the several dozen posts we have written on the various scientists who accompanied Napoleon to Egypt.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.