Scientist of the Day - Powel Crosley, Jr.

Powel Crosley, Jr., an American inventor and industrialist, was born on September 18, 1886 in Cincinnati, Ohio. As a boy he was fascinated with automobiles, even going so far as to build a small, battery-powered car that he and his brother, Lewis, could drive around their neighborhood. Despite his mechanical aptitude, Crosley was a poor student and dropped out of the University of Cincinnati in 1906 to start his own car company. An economic recession the following year led him to set aside those dreams and turn his attention to the automobile accessories market.

Crosley discovered he had a knack for designing simple solutions to the problems confronting car owners and coining catchy names that would capture the public’s interest. His first commercial success (Insyde Tyre) was a rubber lining that surrounded the pneumatic inner tube in car tires and protected them against blowouts. Later inventions included a waterless cleaning compound (Dri-Klean-It), a self-vulcanizing tire patch (Treadkote), and a mechanism to realign a Model T’s steering after it struck an obstacle in the road (the Litl Shofur).

In 1916, Crosley established the American Automobile Accessories Company to produce and sell these inventions, and within five years his firm was grossing over one million dollars annually. He likely would have continued to concentrate on growing that business were it not for a fateful conversation with his nine-year-old son. Powel Crosley III had seen a wireless set in operation while visiting a friend and wondered if his father would buy one for their house. The elder Crosley was amenable to the idea until he discovered that the cheapest radio available at a nearby retailer sold for the exorbitant price of $130 (equivalent to roughly $2,300 today). Instead, he purchased a 25-cent book in the subject and proceeded to build his own crystal set for a fraction of the cost.

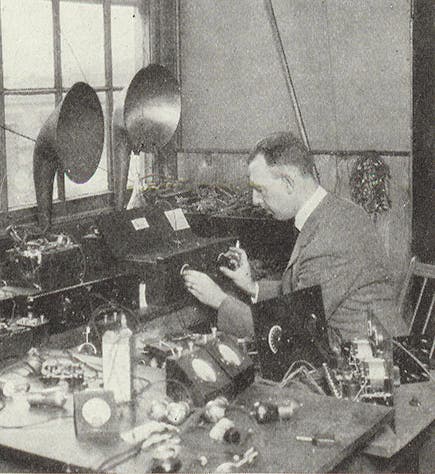

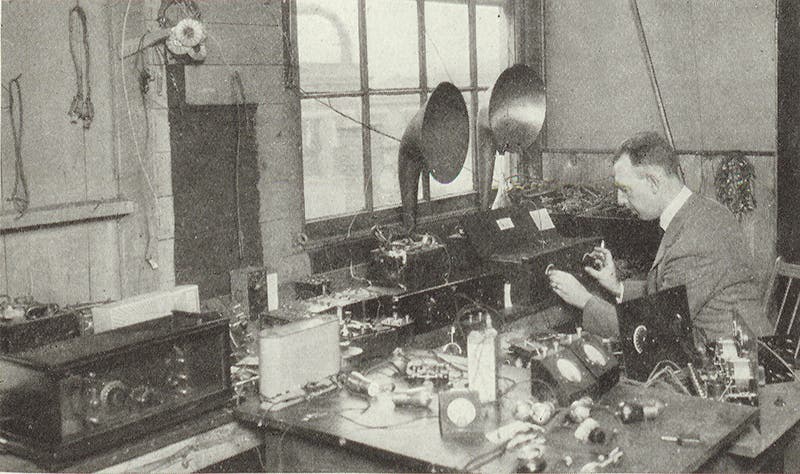

Crosley’s experience persuaded him that there was a market for a more affordable wireless receiver. He recruited a pair of engineering students from the University of Cincinnati to design a radio for the masses. Crosley dubbed the new crystal set the “Harko,” a name derived from the old English word “hark” (to listen), and started selling it for only $7 just in time for the 1921 holiday season. The Harko proved incredibly popular, and Crosley partnered with his brother Lewis to scale up production and develop new models that used vacuum tubes to detect and amplify radio signals. By the end of 1922, the Crosley Manufacturing Company (later renamed the Crosley Radio Corporation) was producing 500 receivers per day, making it the world’s largest producer of radio sets and parts (first image). The Crosleys were also poised to become broadcasters after securing a license to operate a new commercial station, WLW (second image).

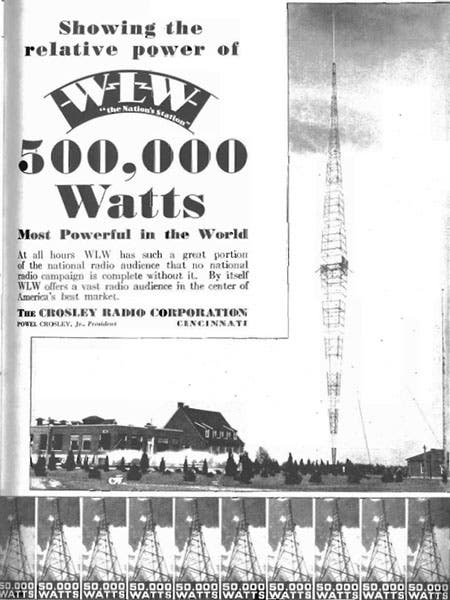

Throughout the 1920s, Crosley responded to Americans’ growing enthusiasm for radio by introducing a variety of new receivers in every price range. In 1925, the company unveiled the “Pup,” a one-tube set that sold for under $10. Because these cheaper radios had trouble receiving weaker signals, he lobbied the FCC to raise WLW’s power output to 50,000 watts in 1928 and later to 500,000 watts in 1934. Due to his commitment to making radio accessible to the masses, members of the press began referring to him as the “Henry Ford of Radio.” Meanwhile, WLW began promoting itself as “The Nation’s Station,” a slogan that reflected the fact that its programs could be heard across the United States (third image).

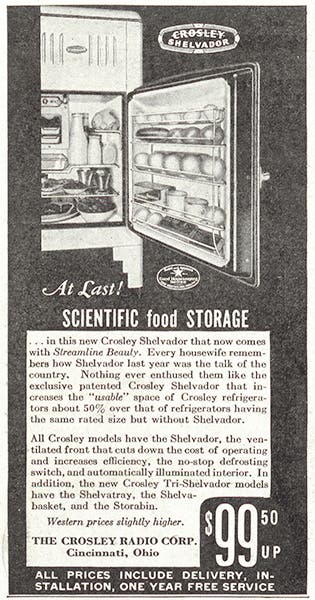

The Crosley Radio Corporation’s rapid expansion came to a dramatic halt following the 1929 stock market crash. As demand for home radio sets declined, the Crosley brothers decided to start making home appliances. Their most successful product was an electric refrigerator with several rows of shelves installed on the interior of the door, which Powel dubbed the “Shelvador.” Though this feature is commonplace today, consumers and retailers hailed the Shelvador as a revolutionary, space-saving innovation when it was introduced in 1933 (fourth image). Sales skyrocketed, and within a year the company was producing over 1,000 refrigerators a day. Other appliance makers found themselves unable to compete since Crosley had purchased the patent for the Shelvador concept from its inventors, Detroit-based engineer Frank West and his wife, Constance. As a result, no one else could manufacture refrigerators with shelves inside their doors until the early 1950s.

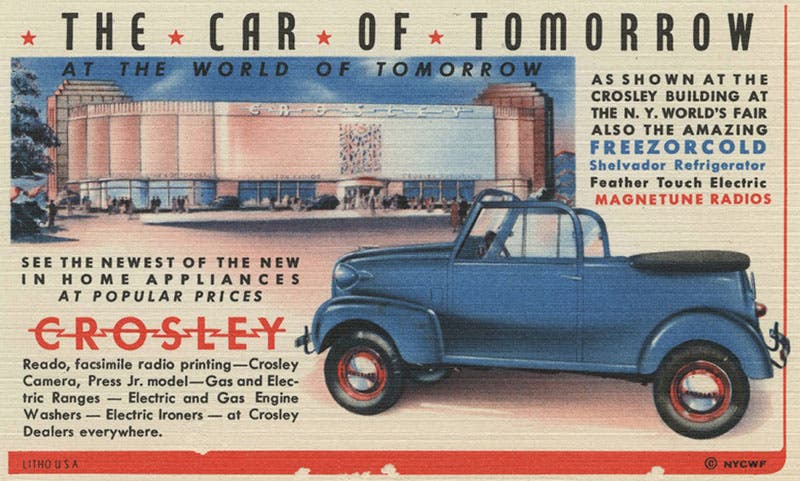

Crosley continued to diversify his business dealings during the 1930s, a move reflected in the eventual decision to drop “Radio” from his company’s name. In 1934, he became the majority owner of his hometown’s baseball team, the Cincinnati Reds, and attracted fans to the newly renamed Crosley Field by broadcasting games on WLW and organizing the first night game in major league history. (The Reds defeated the Philadelphia Phillies with a score of 2 to 1 on the evening of May 24, 1935.) Shortly thereafter, Crosley decided to revisit his childhood dream of building an automobile. As with his first radios, his goal was to create a low-cost car that anyone could afford. The resulting design, a compact model available as both a coupe and sedan (for $325 and $350, respectively), made its public debut in the spring of 1939, just in time to be featured in the Crosley Corporation’s exhibit at the New York World’s Fair (fifth image).

Despite the lack of a dealer network and limited consumer interest in smaller cars, Crosley moved forward with efforts to scale up automobile production. The outbreak of World War II dashed those plans. His company’s assembly lines were repurposed to produce military equipment. In addition to building radar systems, gun sights, and field cooking stoves, Crosley Corporation personnel participated in a top-secret project to develop the proximity fuzes used in bombs and artillery shells. The firm also built and staffed a massive relay station in Bethany, Ohio, whose 200,000-watt transmitters allowed the Voice of America to broadcast news and information into the heart of Nazi-occupied Europe. (The Bethany Relay Station remained in operation until 1994 and is now home to the National Voice of America Museum of Broadcasting.)

By the end of the war, Powel Crosley had grown tired of both broadcasting and consumer electronics. He and Lewis negotiated the 1945 sale of the Crosley Corporation to the Aviation Corporation (AVCO), a conglomerate whose domestic products division was already selling kitchen appliances. He retained control of the firm’s automobile manufacturing operation, which continued to produce sedans, station wagons, and sports cars under the Crosley Motors name for the rest of the decade. Unfortunately, it proved difficult to persuade Americans eager to forget wartime rationing to purchase smaller, fuel-efficient cars. Confronted with declining profits, Powel Crosley finally abandoned his automaking ambitions in 1952. He sold Crosley Motors and spent his final years managing the only business he still owned, the Cincinnati Reds.

When he died of a heart attack in 1961, the Cincinnati Enquirer hailed Powel Crosley as a titan who had left an indelible mark on his city and American society. In light of this assessment, it is striking how quickly his name has faded from public memory. That has begun to change thanks to hobbyists like the Crosley Automobile Club and a Louisville-based company that revived the Crosley brand to market radios and turntables. Meanwhile in Cincinnati, there are ongoing discussions about how best to preserve or redevelop the derelict Crosley Building, which once housed the company’s headquarters, manufacturing facilities, and WLW’s studios. Hopefully, these efforts will spark broader public interest in the Midwestern entrepreneur who reshaped his nation’s radio, electronics, and automobile industries.

Benjamin Gross, Vice President for Research and Scholarship, Linda Hall Library. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to grossb@lindahall.org.