Scientist of the Day - Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a Bavarian-English soldier and experimenter, was born Dec. 17, 1619. Rupert was the son of the Elector Palatine of Bavaria, but also the nephew of King Charles I of England. Rupert came to England to lead the Royal army during the English Civil War, 1642-49. After Charles was beheaded in 1649, Rupert left the country, but he returned after the Restoration of 1660. Rupert was not only a tinkerer (he was the first to bring Prince Rupert's drops to England, small glass tear-shaped drops that shatter violently when struck), but also a reasonably gifted artist. He was one of the first to experiment with the new engraving technique called mezzotint, where the surface of a copper plate is covered with small scratches by a rocker (invented by Rupert); such a plate will hold a large quantity of ink, and will print black. But if the roughened surface is smoothed with a burnisher, those burnished areas will print grey or white.

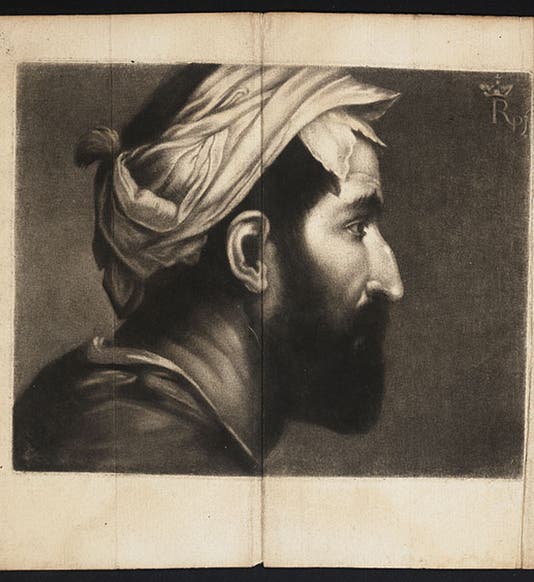

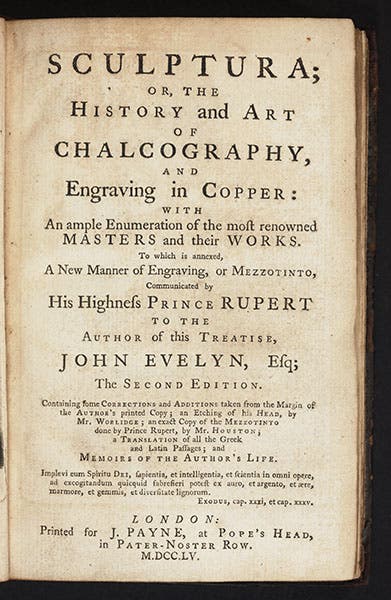

The mezzotint was introduced to England by Rupert, in the form of a letter to John Evelyn, along with a mezzotint portrait of his own making that was printed – letter and mezzotint – in Evelyn's Sculptura (1662). For some reason, the book was reissued almost one hundred years later; we have this second edition (1755; second image) in our collections, with the often-missing mezzotint (first image), and the caption swears that the 1755 engraving is an "exact copy" of the original by Prince Rupert.

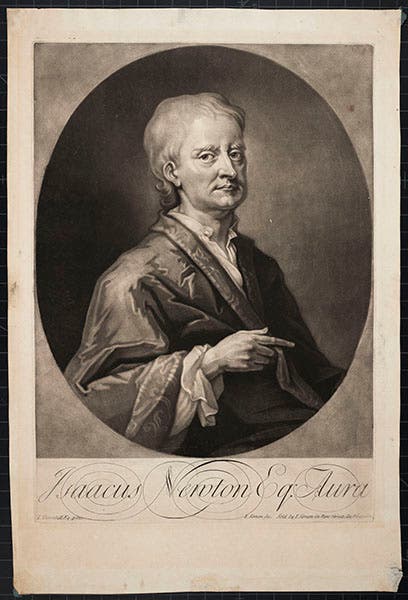

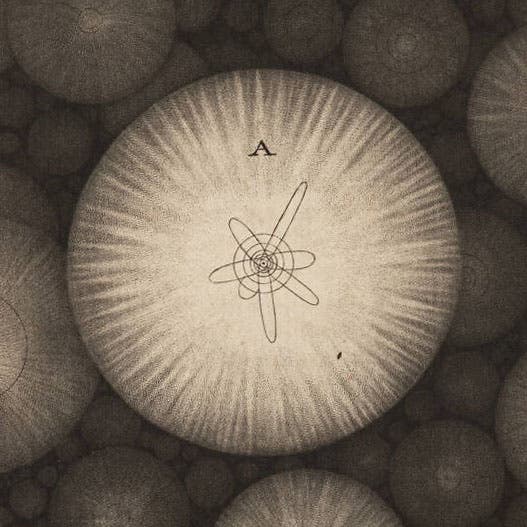

The mezzotint was rapidly recognized as the ideal medium to reproduce portraits. We have in our collections an original mezzotint of an oil portrait of Isaac Newton by Sir James Thornhill (third image). A detail of Newton's hand (fourth image) allows one to see the characteristic signature of a mezzotint, the faint traces of rocker marks in the light areas of the print.

Newton’s hand, detail of third image, showing evidence of mezzotint rocker marks (Linda Hall Library)

Our former Curator of Rare Books, Bruce Bradley, published an article on this portrait and other Newton printed portraits in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London some years ago; you can access it here.

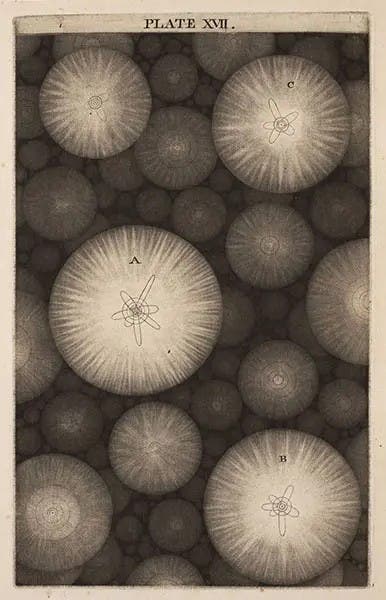

A collection of stellar systems, mezzotint, from Thomas Wright, An Original Theory of the Universe, 1750 (Linda Hall Library)

Mezzotints also became popular for astronomical images that featured the night sky. Thomas Wright used them to good effect in his An Original Theory of the Universe (1750). One plate shows a universe of stellar systems (fifth image); a detail of our solar system reveals its mezzotint origin (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.