Scientist of the Day - Rainhill Trials

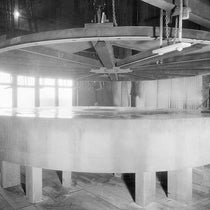

The famous Rainhill Trials began on Oct. 6, 1829, on a railroad track near Manchester, England, and ran through Oct. 14. The purpose of the trials was to determine if a moving locomotive was superior to a standing engine in moving railway carriages, and if so, to find the best one. The trials were organized by the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which had completed most of the 35 miles of track between the two cities, as well as two tunnels, quite a few bridges and culverts, and a passage over a peatbog. Now they needed a locomotive that could haul railway carriages over the track.

Each locomotive entered in the trials had to negotiate a mile-and-three-quarters track, back and forth, ten times – the equivalent of the distance from Liverpool to Manchester – and then do the same again, as if making a return trip. Each locomotive pulled a load equal to three times its own weight, and had to maintain a speed of 10 miles-per-hour to be considered for the prize. It also had to “consume its own smoke.”

Ten engines, made by 10 different individuals or companies, were entered into the competition, but only five actually competed: the Rocket, the Novelty, the Sans Pareil, the Perseverance, and the Cycloped (the latter powered by a horse on a treadmill). All were steam engines except the Cycloped (whose horse fell through the floor and ruined his owners’ day).

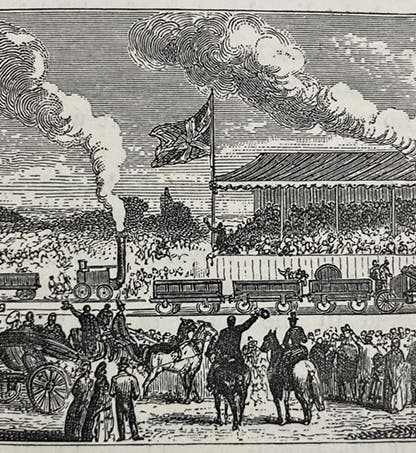

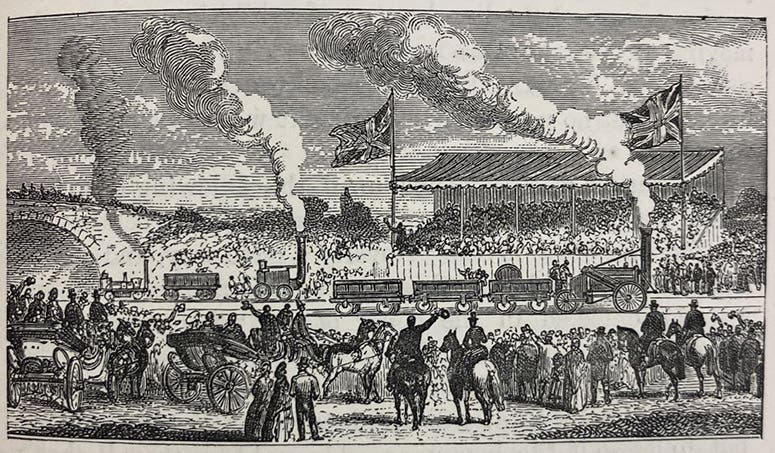

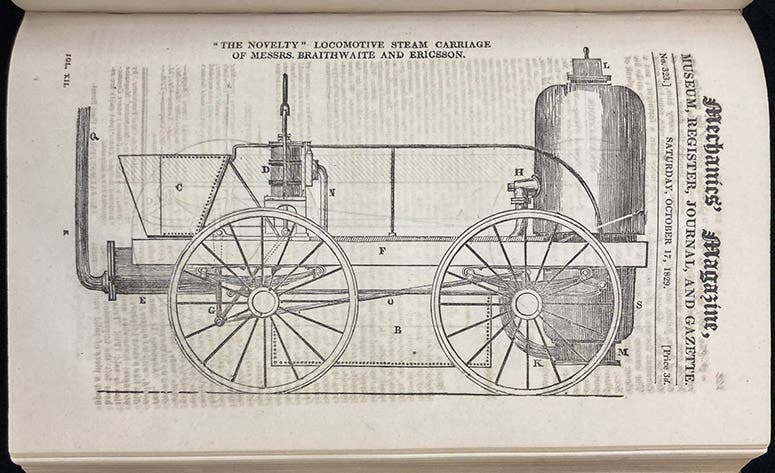

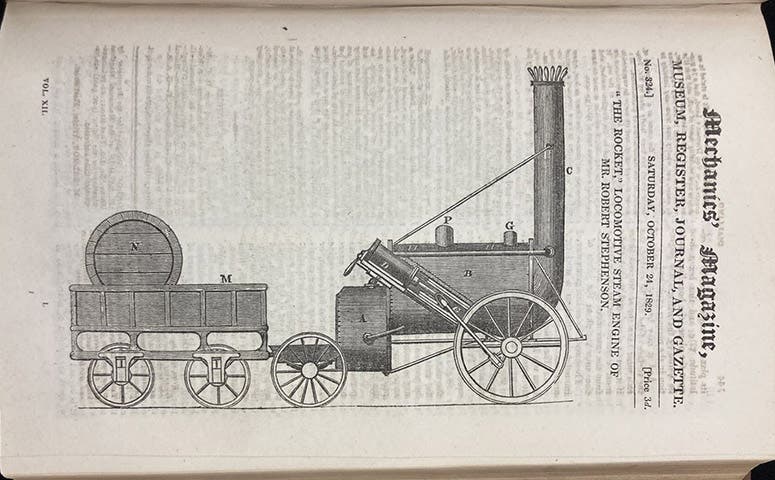

Quite a crowd gathered on that first day, estimated at 10-15,000, and their favorite was clearly Novelty, which wowed everyone when it got up to the unheard-of speed of thirty miles per hour. The trials went on for just over a week, and all of the contenders but one succumbed to burst pipes, cracked cylinders, or other mechanical failures. The only engine to finish the course was Rocket, entered by the father-and-son team of George and Robert Stephenson (George, the father, built the Liverpool and Manchester Railway; son Robert built the Rocket). As winners of the £500 prize, the Stephensons not only demonstrated the viability of moving locomotives, but won the contract to supply engines for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which opened the next year, in 1830.

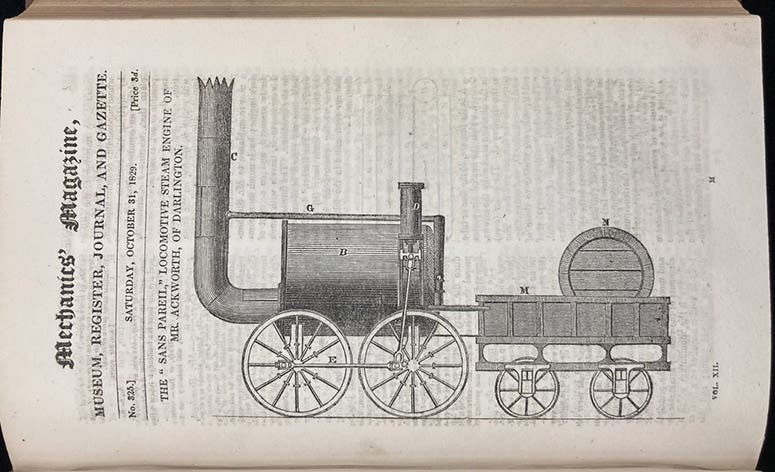

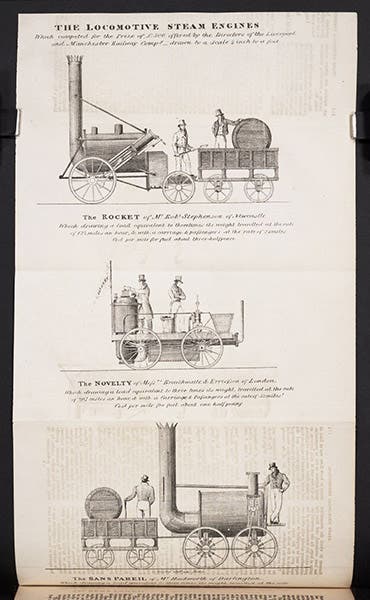

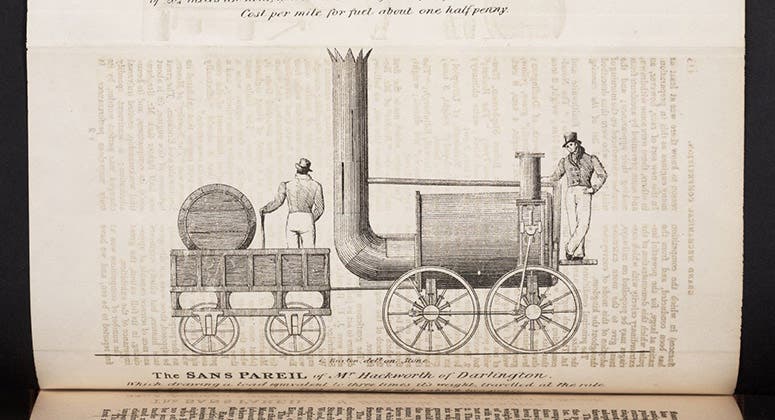

There were many contemporary accounts of the Rainhill Trials in Manchester and London newspapers, but we do not have any of those in our collections. But we do have a run of the Mechanics' Magazine, Register, Journal, and Gazette, a relatively new journal at the time that came out weekly and whose editors jumped on the story, sending reporters to the scene and commissioning woodcuts of the three major contenders, which they ran on the covers of the Oct. 17, 24, and 31 issues. The issue of Oct. 10 covered the first two days of the trials, and provided detailed descriptions of the different locomotives. The editors clearly favored the sleek Novelty and its two engineers, John Ericsson and John Braithwaite, but duly congratulated the Stephensons and Rocket.

Interestingly, the three woodcuts on the three covers were at different scales, and the illustrator unfortunately put the tender on the wrong end of the Sans Pareil. So for the Nov. 28 issue, the editors commissioned a large lithograph that shows all three locomotives at the same scale, and moved the tender of the Sans Pareil to the proper end of the locomotive. In our volume, the lithograph has been folded up and bound in with the Oct. 10 issue, which is where it really belongs, but that is not when it was issued. We show you both the full plate (fifth image), and a detail of the Sans Pareil from the lithograph (sixth image), which you can compare to the original woodcut (fourth image).

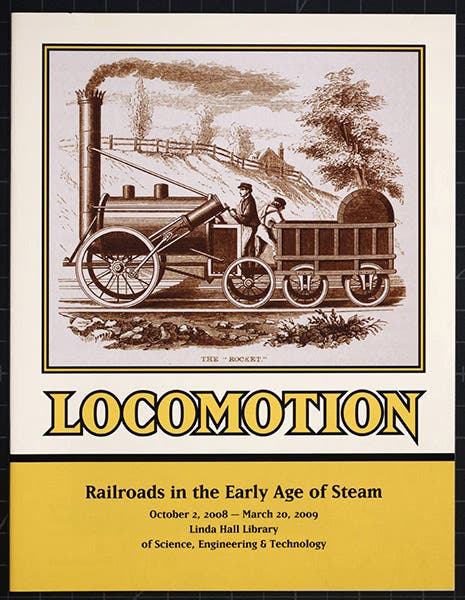

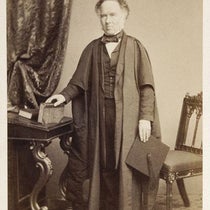

There is a discussion of the Rainhill Trials, reproducing the lithograph from the Mechanics’ Magazine, in our exhibition brochure, Locomotion (2008), which was curated by Bruce Bradley, with a dramatic later wood engraving of the Rocket on the cover (seventh image). That catalog is available online. You might also consult our posts on George Stephenson, Joseph Locke, and Samuel Smiles, whose book, The Lives of the Engineers (1861-62) was the source for our first image, and for the image on the cover of Locomotion.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.