Scientist of the Day - Ralph Alpher

Ralph Alpher, an American theoretical physicist, died Aug. 12, 2007, at age 86. During World War II and the succeeding years, Alpher worked during the day for the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, part of the Carnegie Institution, and then the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University, and attended George Washington University (GWU) at night, earning, successively, his BA, MA, and PhD in Physics, which was not at all an easy schedule to manage in any field, much less theoretical physics.

At GWU, he hooked up with GWU's most famous physicist, George Gamow, who had fled from his native Russia in the 1930s. Gamow supervised Alpher's doctoral dissertation, which was on nucleosynthesis in the Big Bang. Alpher worked out the likelihood that, as matter cooled in the seconds after the Big Bang, neutrons and protons would hook up to form deuterium, helium, and all the rest of the elements, going right up the periodic table. This was quite a feat, at a time when the Big Bang was still only a gleam in a few cosmologists’ eyes, and when in fact the Big Bang hadn't even yet been named (this would come in 1950).

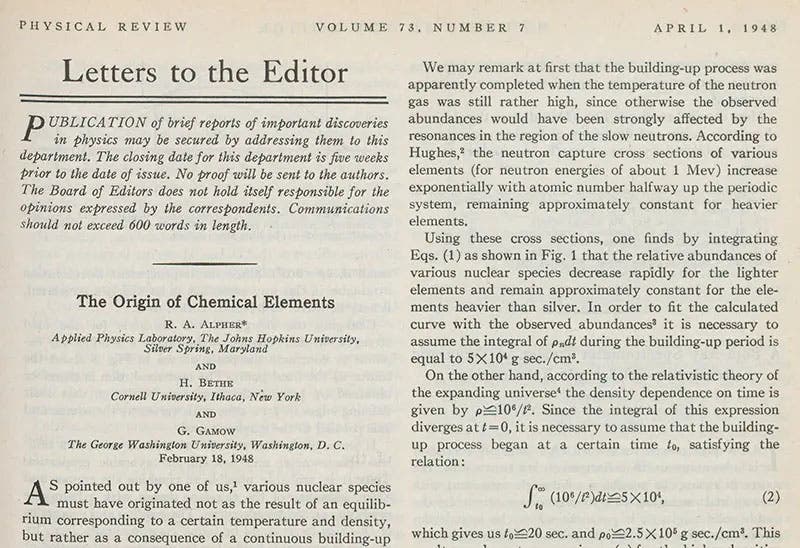

Before Alpher could defend his dissertation, Gamow arranged for himself and Alpher to publish a summary paper, "The origin of chemical elements," in the respected journal Physical Review. Gamow, however, was an inveterate jokester, and he couldn't help noticing that the two author names, Alpher and Gamow, sounded very much like the first and third letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha and gamma. Wouldn't it be nice, Gamow must have thought, if we could find a third author whose name sounded like beta, the second Greek letter. Fortunately for the continuation of the joke, there was just such a man: Hans Bethe, the eminent nuclear physicist who had emigrated from Germany during the rise of Hitler and had settled in at Cornell, where he had become an essential member of the Manhattan Project. Accordingly, Gamow wrote Bethe's name in between his and Alpher's and sent the paper off. And it was published just that way, becoming known instantly as the "alpha-beta-gamma" paper (third image). Gamow was amused, and Bethe was amused (after all, Bethe had his name attached to one of the most significant papers in modern cosmology, without doing a thing). Alpher, however, was not so amused. The paper was mostly his work, and he feared that his contribution would be overshadowed by the luminous names of Gamow and Bethe. And he was right. Nearly everyone attributes this attempt at a Big Bang nucleosynthesis to Gamow.

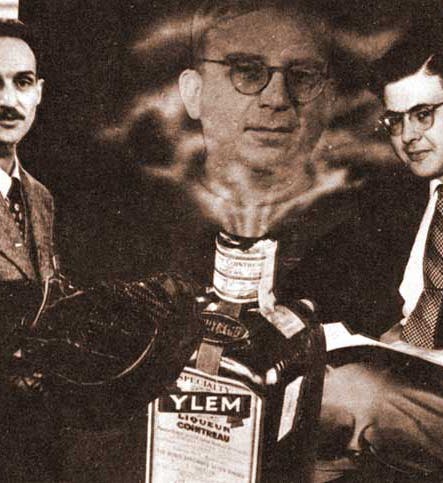

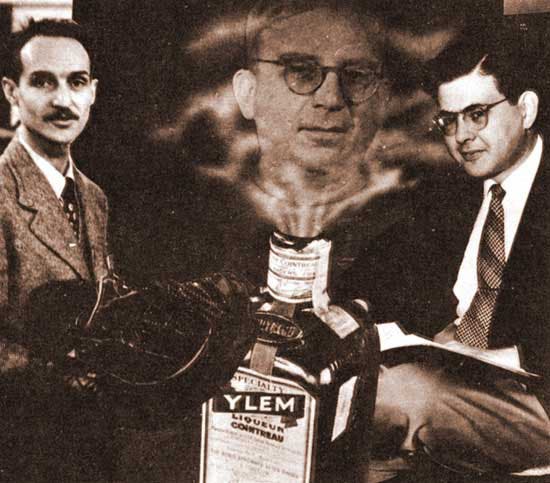

In a composite photo, put together by Gamow as a joke (first image), Alpher is at the right, Robert Herman (more on Herman below) is at left, and Gamow is shown emerging from the genie’s bottle in the center (a Cointreau bottle that has been labelled “Ylem”, or primordial stuff):

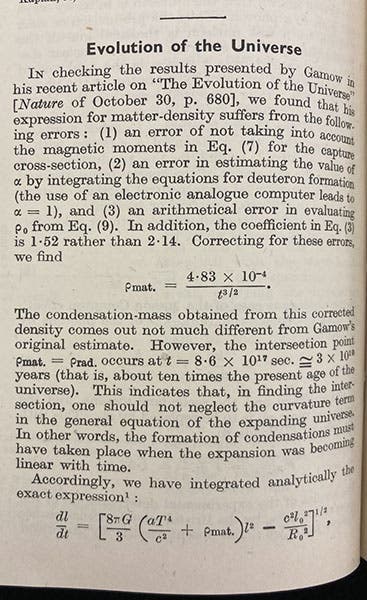

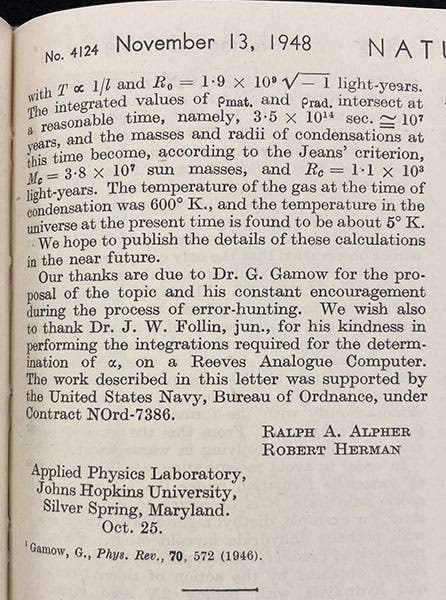

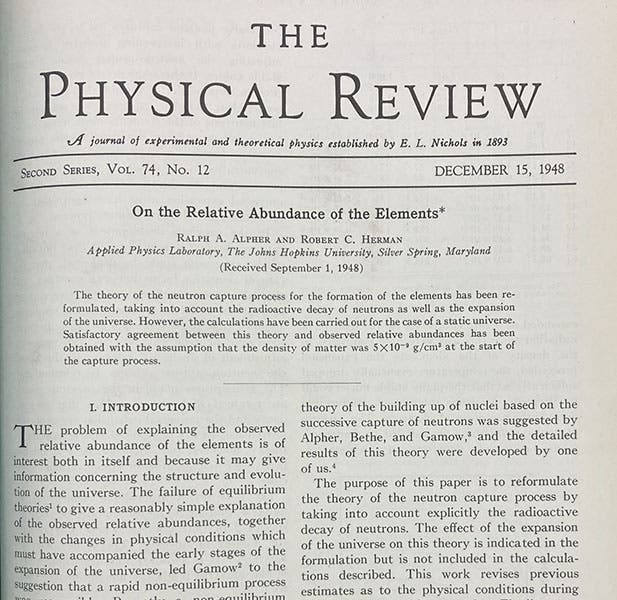

That same year, 1948, Alpher wrote and published two papers with Herman, another Gamow student, in which they predicted that, as the universe cooled after the Big Bang, it should have left behind a residual temperature signature, detectable even today. They even predicted the amount of the residual temperature – 5° Kelvin (or 5 kelvins, as we would now say). I have never seen either of these two papers reproduced, so I include the first paragraphs of both, and the section of the first paper where the figure “5° K” appears (fifth image).

Alpher’s and Herman’s papers failed to elicit any immediate response, but 15 years later, a team of physicists at Princeton, led by Robert Dicke, made the same prediction of a residual temperture, without mentioning (or even knowing of) Alpher’s and Herman’s work, and a year later, two Bell Lab engineers, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, detected the temperature residue of the Big Bang, now called the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) or Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (CMBR). For their discovery, Penzias and Wilson shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978. Nowhere in any of the proceedings was there any mention of Alpher’s and Herman’s seminal contribution.

Alpher became a somewhat bitter man in his later years, not at all pleased that he was completely left out of most accounts of the proposal and reception of the Big Bang theory, or of the discovery of the CMBR. It is hard to blame him too much. Myself, I blame Gamow. He was alive and working in 1964 (even though he was now messing with the coding of DNA), and he could certainly have raised a voice and said: “my guys discovered this back in 1948,” and other physicists would have paid attention. But he chose not to take up the case of his students. Perhaps his ill health (he would die of liver failure in 1968) prevented this. Fortunately, recognition started to come in the 1990s, as Alpher and Herman shared several awards, and in 2005, Alpher was awarded the National Medal of Science, as prestigious an award as this country has to offer. It’s just too bad for Alpher’s mental well-being that the award had not come 30 years earlier.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.