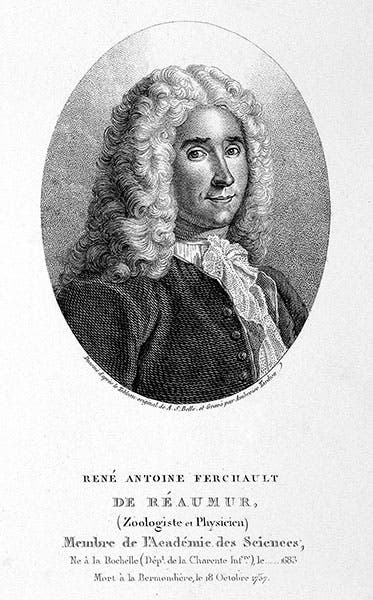

Scientist of the Day - René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur

René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, a French naturalist, was born Feb. 28, 1683, in La Rochelle. Réaumur came to Paris when he was 20 years old, and eventually became one of the most respected naturalists in France, before Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, stole most of the limelight for himself. Réaumur is best known for his six-volume Mémoires pour servir a l'histoire des insectes, which was published between 1723 and 1742. Réaumur's conception of insects, in those pre-Linnaean days, was a broad one, as it also included spiders, mollusks, crustaceans, and even reptiles. We have written two posts on Réaumur’s Memoires des insectes, the first, eight years ago, a more general account, as most of our posts were in those days. Then, just last fall, we wrote a more expansive post, in which we provided details of some of the wonderful engraved headpieces that Réaumur used to introduce each volume.

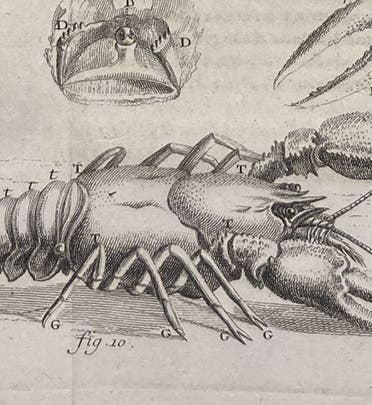

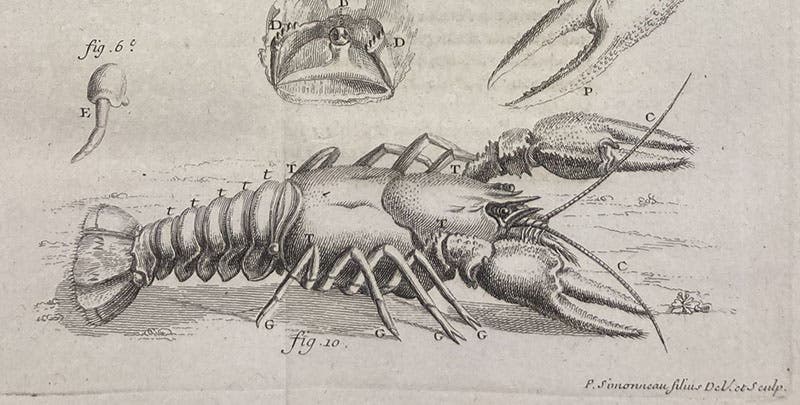

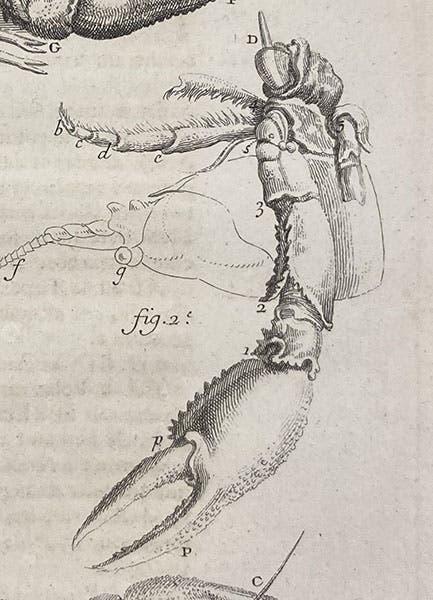

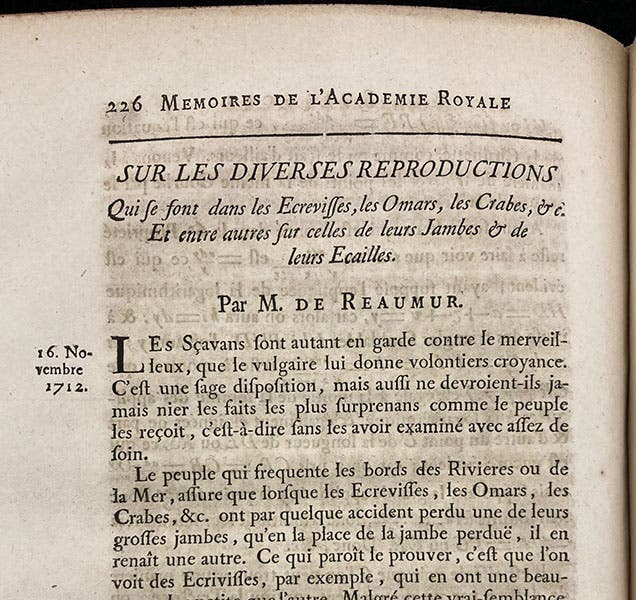

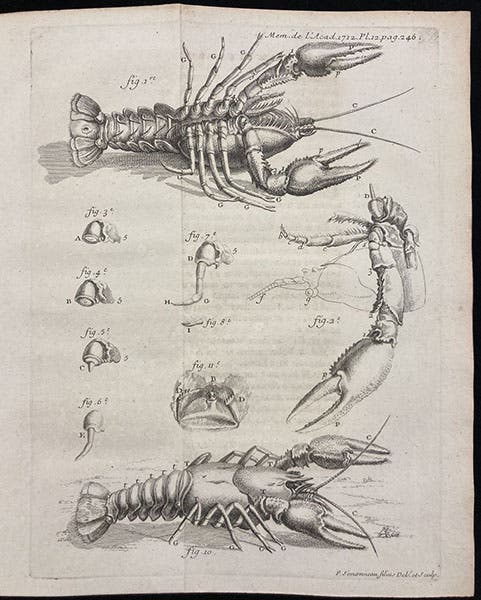

Today we are going to look at Réaumur's first major paper, printed in the Memoires of the Royal Academy of Science in Paris, a journal only 12 years at the time. It was called: “Sur les diverses reproductions qui se font dans les Ecrevisses …,” (“On the various regenerations which occur in Crayfish …”). In some circles, such as those around Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, who works on regeneration in planaria at the nearby Stowers Institute (and who is a trustee of our Library), Réaumur's first paper is his most important contribution to biology, since he showed that crayfish can regenerate severed limbs, and this was long before the regeneration of planaria and hydra had been discovered. Réaumur had observed that crayfish occasionally lose appendages in the molting process, and he found that if crayfish limbs, even their claws, were artificially severed, they would eventually grow back (third and fourth images).

A crayfish, top and bottom view, with a detail of a regenerated claw, folding engraved plate in René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, “Sur les diverses reproductions qui se font dans les Ecrevisses …,” Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, avec les Memoires … année 1712, plate 12, p. 246, publ. 1714 (Linda Hall Library)

This was a sensational discovery in 1712, because it conflicted with the prevailing theory of embryology, known as preformation, or emboîtement. According to preformationists, all of the parts of an individual organism were already there in the egg, (or the sperm), and so development was simply the unfolding of pre-existing parts – no further plan was needed to tell the embryo how to make a heart, for example – it was already “in there,” and just needed to grow.

How then did a crayfish regenerate a claw? A claw was a reasonably sophisticated appendage, so how was the crayfish able to make a new one? This seemed to require a plan, another word for an animal soul. René Descartes had put the kibosh on animal and vegetable souls with his mechanistic view of living things, and most French natural philosophers, in 1712, were Cartesians. Réaumur gave them a real problem to chew over. Réaumur himself thought the problem was solvable within Cartesian parameters, by postulating the existence of subsidiary “eggs,” one at each joint, containing the remainder of the limb in miniature, ready to grow should the old limb be lost. But others found the fact of regeneration to be a fatal blow to Cartesian mechanism, and vitalism, which postulates that living things are more than just material things, became more and more popular as the century moved on, especially after Abraham Trembley discovered in 1740 that when a hydra is cut in half, each half can regenerate a complete organism.

If you are further interested in the history of regeneration, we have published posts on Abraham Trembley (hydra), John Graham Dalyell (planaria), and Henry Van Peters Wilson (sponges). I have written several posts about Peter Simon Pallas, but I have not discussed his discovery of planaria regeneration in 1774; I should put that on the agenda of upcoming anniversaries.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.