Scientist of the Day - Robert Dietz

Robert Sinclair Dietz, an American marine geologist, died May 19, 1995, at the age of 80. Dietz earned his degrees from the University of Chicago, but did most of his graduate work at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, where he helped map the Pacific Ocean floor. He was a flight instructor during World War II, and after the war took a job at the new U.S. Navy Electronics Lab in San Diego, where he worked from 1946 to 1963, and was pretty much left alone to do what he wanted. That was mapping sefloors, as he and others were discovering such things as seamounts and guyots, which were flat-topped structures that littered the Pacific Ocean floor.

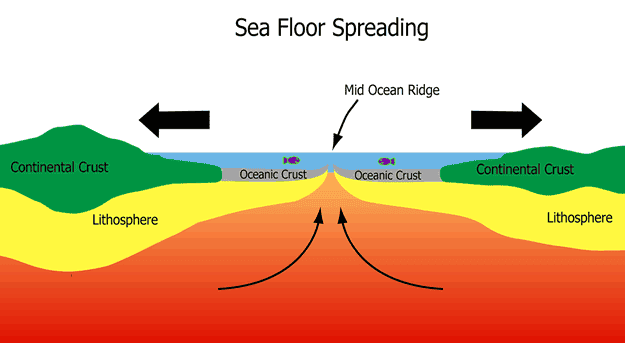

Continental drift was on the radar of most geologists at this time, but there were very few adherents in the mid-1950s. Dietz does not seem to have been a "mobilist" (as we now call defenders of crustal movement) until 1956, when he attended a conference at which paleomagnetic evidence for the movement of continents was offered, in abundance. Still, up until 1961, Dietz’s idea of crustal motion was up or down, not sideways. He believed that the recently discovered oceanic ridges (such as the Mid-Atlantic ridge), were caused by convection cells in the mantle that slowly bring up material from the mantle and extrude it at the ridge. But he does not seem to have had the idea that the ocean floor could originate at ridges and move sideways in both directions, pushing continents along in the process.

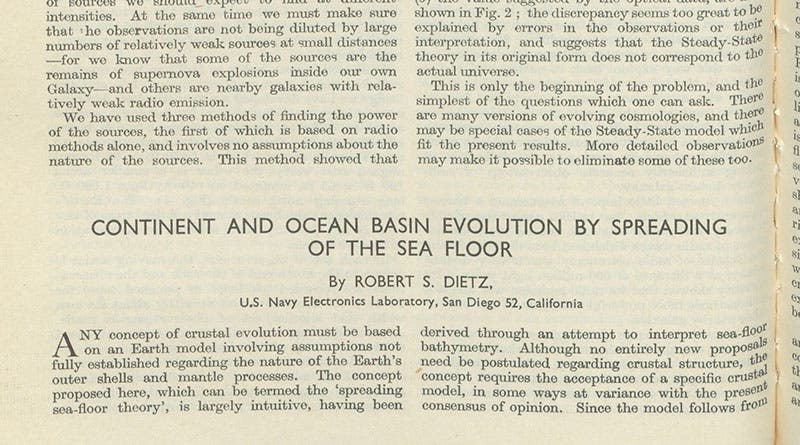

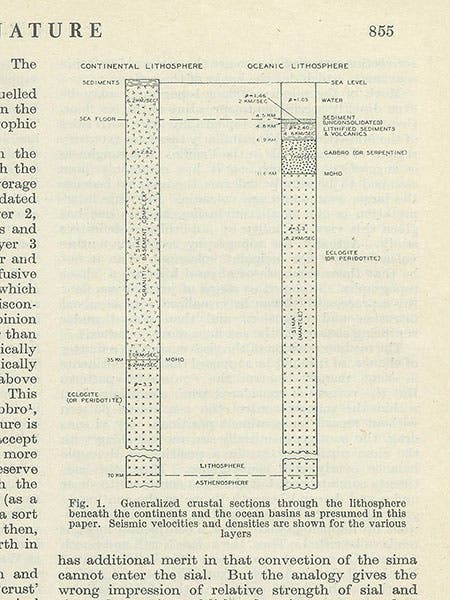

Rather suddenly, in June of 1961, Dietz published a short paper in Nature, "Continent and Ocean Basin Evolution by Spreading of the Sea Floor." In his paper, he argued that the mid-oceanic ridges are places were new material wells up from the mantle, and solidifies to form new ocean floor, slowly pushing the existing floor apart. He pointed out that this would explain much recently acquired data, such as the curious fact that the layer of sediment on the Atlantic Ocean floor is very thin, and that cores contain no fossils older than the Cretaceous, i.e., the last 65 million years. Dietz did not propose the existence of subduction zones, where old ocean floor is pushed down into the mantle to make way for the newer crust – that would come later. But he did coin the word "sea floor spreading" for the phenomenon he was describing, a term still in wide-spread use (fourth image).

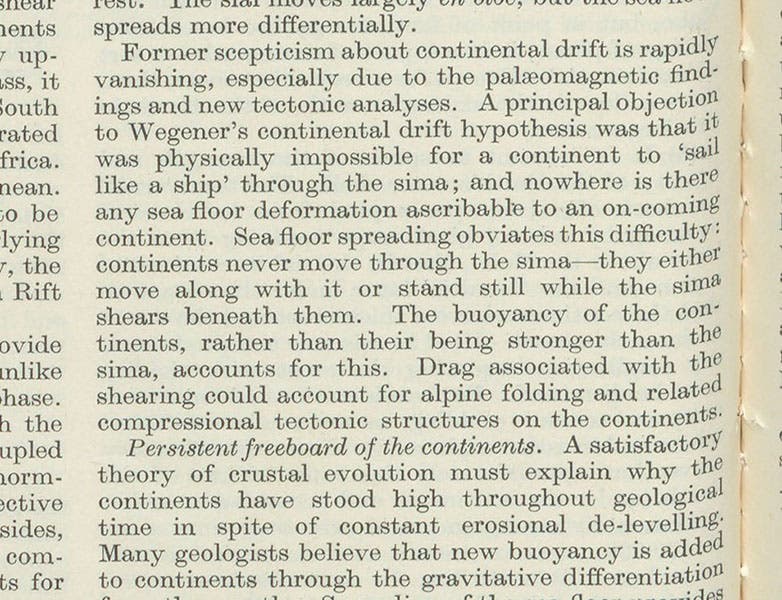

The only problem, and a rather serious one, was that Harry Hess, at Princeton, had already come up with the idea of sea floor spreading and had circulated a preprint of his paper well before Dietz's paper was even written. Dietz knew Hess personally and had visited him at Princeton in November of 1960. Hess's firm recollection was that he told Dietz all about his idea in 1960, and that Dietz then published his paper without mentioning his discussion with Hess. Dietz maintained that he had not discussed sea floor spreading with Hess during the Princeton visit, and that he came up the idea on his own. However, in a subsequent paper, perhaps under pressure from his peers, he acknowledged that Hess deserved priority for the concept (although credit for the term "sea floor spreading" would stay with Dietz).

Henry Frankel, in vol. 3 of his authoritative The Continental Drift Controversy (2012), analyzed the chain of events, and the papers and correspondence, as thoroughly as could be done, and his opinion was that the Princeton meeting did take place, and that Dietz learned about sea floor spreading from Hess. He acknowledged that Dietz, a maverick of sorts, was certainly capable of coming up with the idea on his own, given his knowledge of marine geology. But there is just no evidence that he did so. Hess, himself, in a letter of 1963, stated in no uncertain terms that he discussed the idea with Dietz, and that Dietz stole the idea from him.

One fact is quite clear – Dietz did not see the Hess preprint before he submitted his own paper. Otherwise, his graphics would not have been so poor. Dietz’s only diagram was one that compared sections of oceanic and continental crust, trying to show where the slippage takes place that is necessary if the oceanic crust is to move over the mantle (sixth image). Hess's paper (published in 1962) has much better diagrams – a section of mid-oceanic ridge with newly created ocean floor, a diagram of a mantle convection cell to show how material is brought up on one side and down on another, and a section of an entire ocean floor, showing how the guyots slowly move to either side and eventually disappear down trenches. You can see all three of these at our post on Hess.

No one talks about it (not even Frankel), but I suspect that Dietz never fully recovered his reputation after his failure to credit Hess in his initial paper. Nevertheless, in spite of this lapse in judgment (or failure of memory), Dietz seems to have been a likeable character. He was never afraid to advance an oddball idea – he proposed once that the great ocean basins of the world were caused by meteorite impacts – and he had other clever ideas. For example, in 1958, he suggested to the U.S. Navy that they buy the Trieste, the bathysphere of Jacques Picard, and sponsor further deep dives down into oceanic trenches, and the Navy did so. Picard wanted to take Dietz along as his second on his famous seven-mile dive of 1960 into the Marianas trench, but the Navy insisted that the other member of the dive should be a naval officer, and Dietz was denied that experience. Dietz was also willing to speak up, where other scientists were not, when the creation science movement began in the late 1970s, and he spent a great deal of time debating creationists and refuting their claims. So in his cosmic ledger, I would guess that Dietz had far more positive points than negative ones.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.