Scientist of the Day - Robert J. Hay Cunningham

Robert James Hay Cunningham, a Scottish geologist, died May 15, 1848; one source says he was just 27 years old at the time of his death, which I doubt, because we are going to discuss a book of his, published in 1838, that could hardly have been the work of a 17-year-old. We don’t know when he was born, and we know practically nothing about his life, except that he was intimately familiar with the geology of the area known as the Lothians, the region that extends across southern Scotland and includes Edinburgh and the Firth of Forth. We know this because of his book, Essay on the Geology of the Lothians (1838), a splendid copy of which resides in our history of science collections.

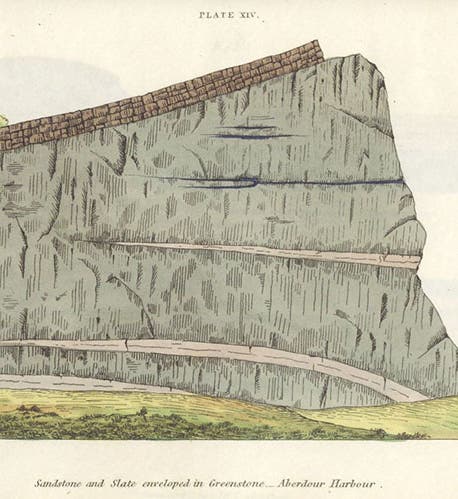

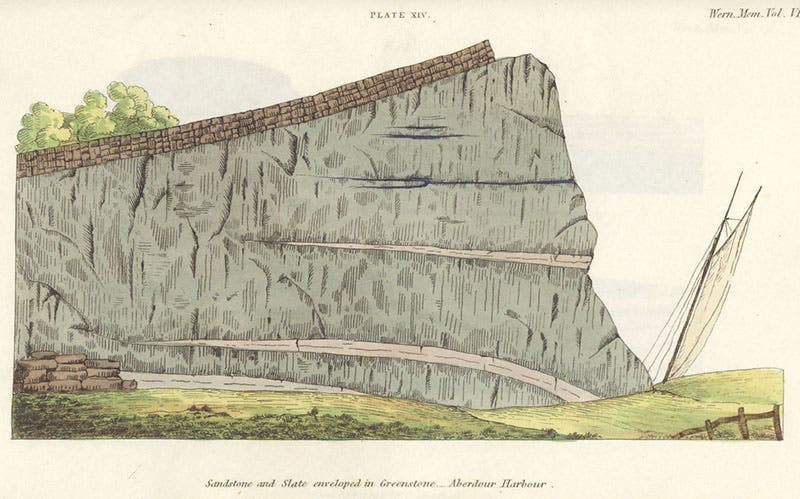

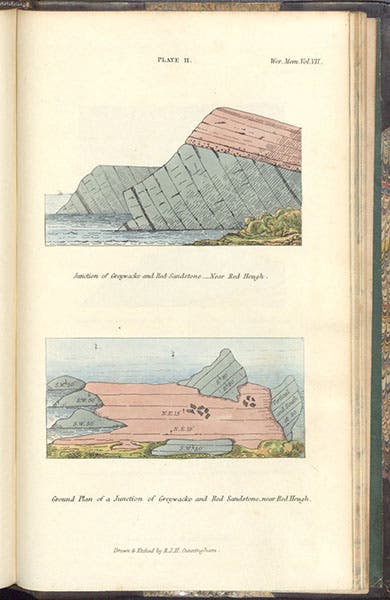

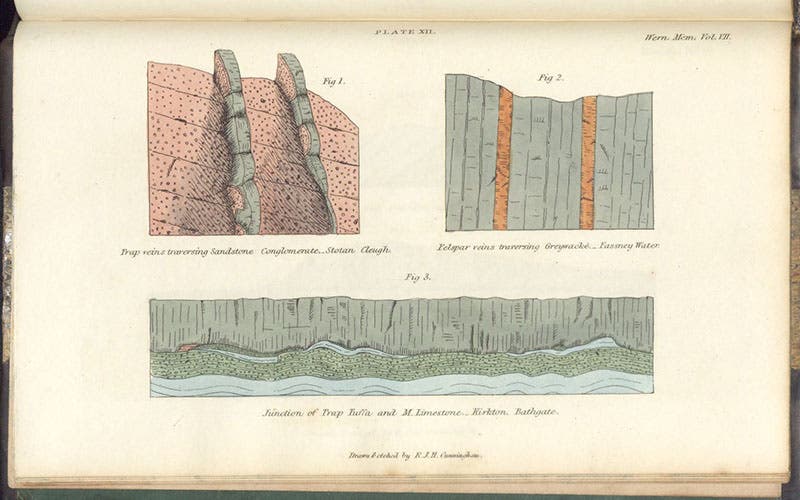

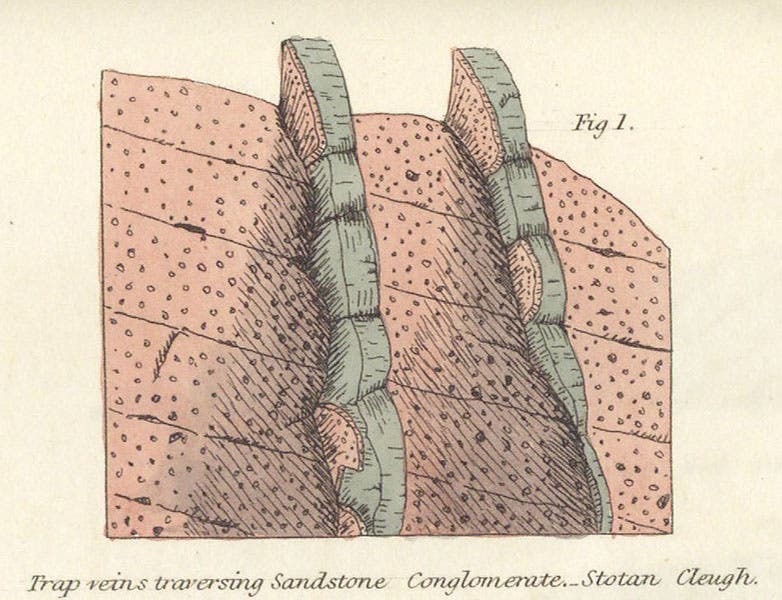

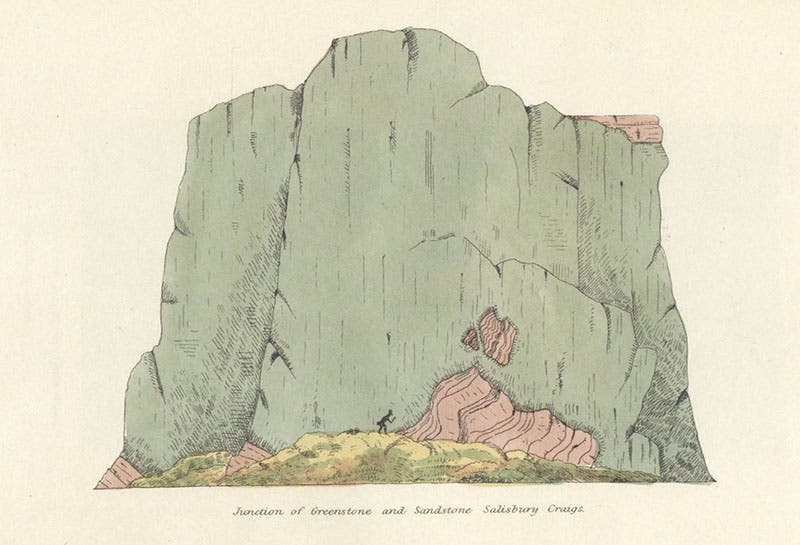

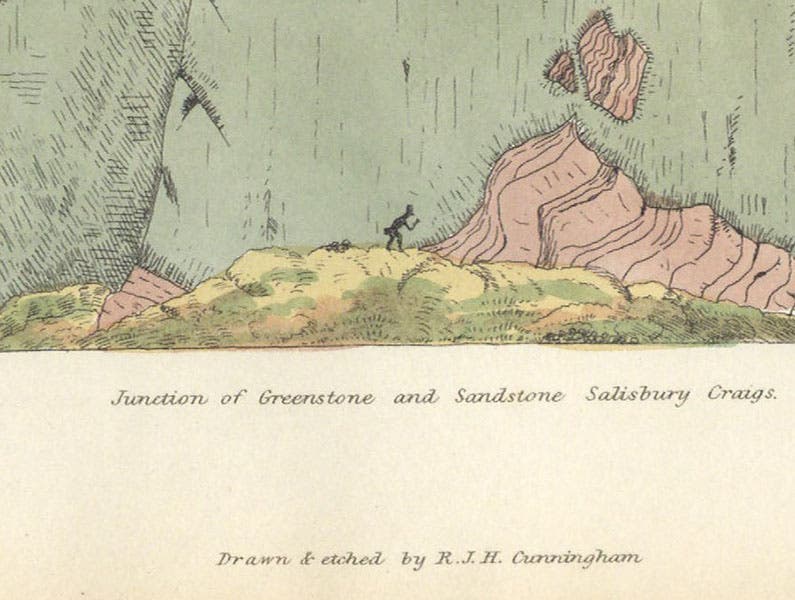

Cunningham’s Essay on the Lothians is in fact a personal favorite of mine, of all our geological books, and we have quite a few. I like it because it has a fine but not showy binding, and because the hand-colored etchings at the end are exquisitely produced, with careful coloring, each one making a clear geological point Most of the images show what we would call intrusions, where once igneous greenstone, basalt, porphyry, or trap has forced its way between layers of limestone, sandstone, greywacke, or shale. In 1838, however, not everyone considered basalt or greenstone to be an igneous rock. Many, especially the members of the Wernerian Natural History Society in Edinburgh, led by Robert Jameson, thought that all rocks except lava were sedimentary in origin. I do not know how anyone could leaf through the 16 plates at the end of Cunningham’s book and emerge with that belief intact.

Since we know so little about Cunningham, we will simply show you several of his plates (which he drew and etched himself, by the way; see eighth image) and relate what we can learn about him from the text, Since the plates are so devoted to igneous intrusions, one might suppose Cunningham to have been a follower of James Hutton and John Playfair, who argued for the igneous origin of greenstone and basalt, but Cunningham does not mention Hutton or Playfair anywhere in the book. It’s as if he became a plutonist all on his own, by just observing the local strata and the intruding greenstone. That is certainly possible. He did know the work of John McCullough, whose geological map of Scotland came out in 1836, but Cunningham is often critical of McCullough’s interpretations. He really wanted to do this all on his own.

One of Cunningham’s most arresting plates is the one that shows a section of the Salisbury Craigs, where some underlying sandstone melted and broke off under a flood of molten greenstone, and some of the fragments floated up into the greenstone and solidified there when everything cooled (seventh image). This section was observed by Hutton, and he used it to argue for the igneous origin of basalt – indeed, it is called “Hutton’s section” to this day. You can see that there is a tiny figure with a rock hammer investigating the sandstone fragments, and it is easy to imagine this as Hutton himself (eighth image). When I taught the history of geology (and when I wrote the post on Hutton), I always used this plate to illustrate Hutton’s geology. Yet it is apparently not Hutton in the engraving – or if it is, Cunningham kept that fact a secret. It is more likely to be Cunningham himself.

Tiny figure with rock-hammer (James Hutton?) investigating sandstone fragments “floating” in the greenstone at Salisbury Crags, detail of seventh image, Essay on the Geology of the Lothians, by Robert J. Hay Cunningham, 1838; note that Cunningham drew and etched the plate himself (Linda Hall Library)

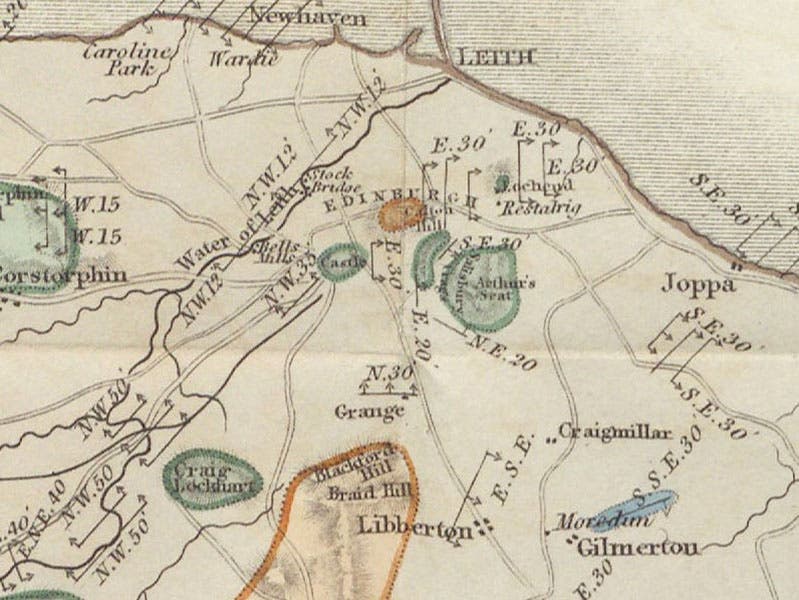

The Essay on the Geology of the Lothians also contains a large folding geological map of the Lothians. Like most geological maps, it doesn’t show up well in a small reproduction (ninth image). So I include a detail of the Edinburgh area, which, on the map, is just to the left of center, below the Firth of Forth (tenth image). Arthur’s Seat, a small igneous mountain, and the Salisbury Craigs are both identified by labels, which you may or may not be able to make out at this scale.

Before his death in 1848, Cunningham also completed a geological map of Sutherland County in the northern highlands of Scotland, which must have been quite difficult for a lone geologist – hiking the area is much more arduous than traipsing through the Lothians. We do not have this map or the memoir that accompanied it. It would be nice to acquire it.

I am sorry to say that I know of no portrait of Cunningham (unless that is him in our seventh and eighth images), nor could I discover where he is buried. So I am extra pleased that we have his beautiful Essay to remember him by.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.