Scientist of the Day - Sherard Osborn

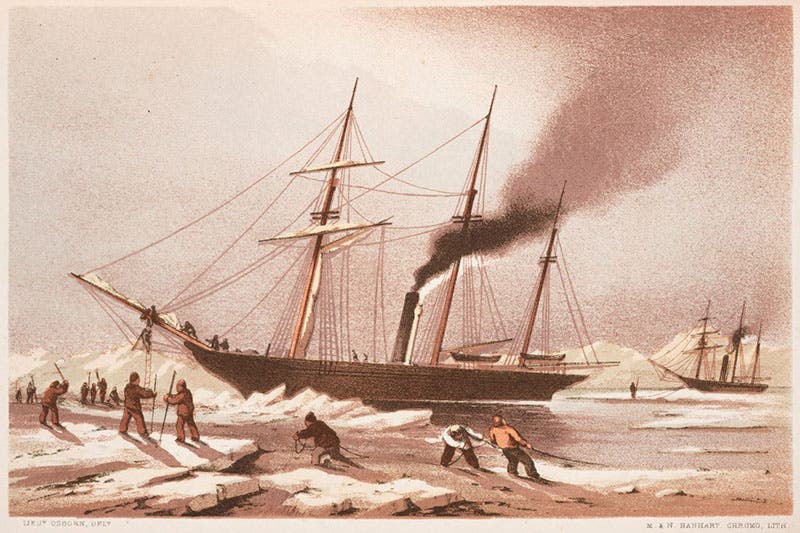

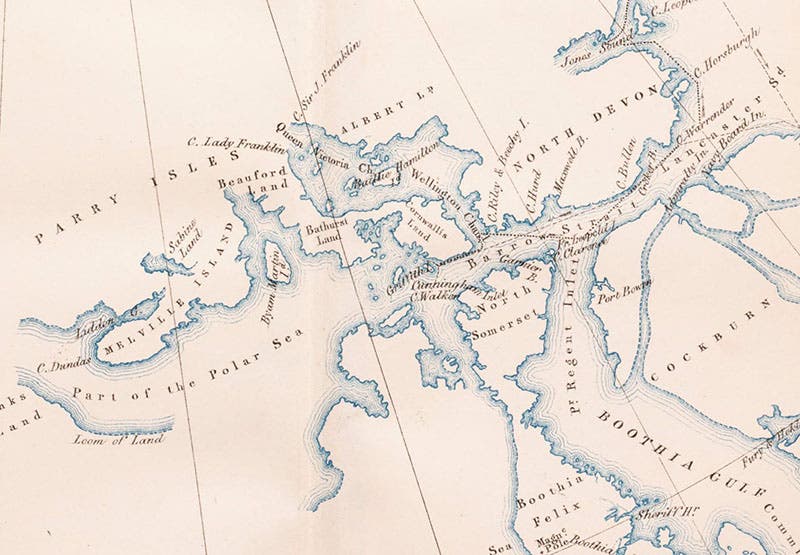

Sherard Osborn, a Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer, was born Apr. 25, 1822. Osborn was the commander of HMS Pioneer, one of the four ships sent to the Arctic in 1850, under the command of Capt. Horatio Austin, to search for the lost Franklin expedition, which had left England in 1845 and had not been heard from since 1847. Osborn's ship, the Pioneer, was a steam-tender, serving the larger Resolute as an ice-breaker and as a tow-boat in harbor or when the wind was an insufficient motor (fourth image). The ships headed straight up Baffin Bay and through Lancaster Sound to Barrow Strait in the midst of the Arctic archipelago (see map, third image), from which they fanned out to search the various other sounds and straits that ran in every direction. There were two other British ships in the area, commanded by William Penny, and two American vessels, all there at the same time for the same purpose – to find Franklin. They found the graves of three of Franklin's men on Beechey Island, and some abandoned tins of food, and several cairns, but inexplicably, no documents that indicated in what direction Franklin’s ships had gone.

The region around Griffiths Island (center) in Barrow Strait in the Arctic archipelago, where the Austin expedition wintered in 1850-51, and which was explored by 8 sledge parties in the spring of 1851, detail of hand-colored engraving in Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal, by Sherard Osborn, 1852 (Linda Hall Library)

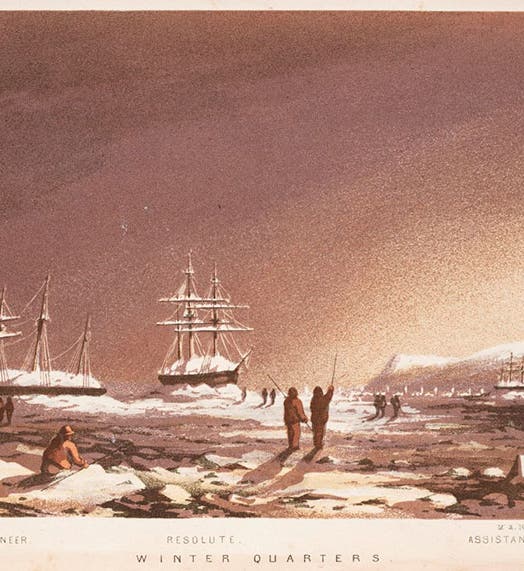

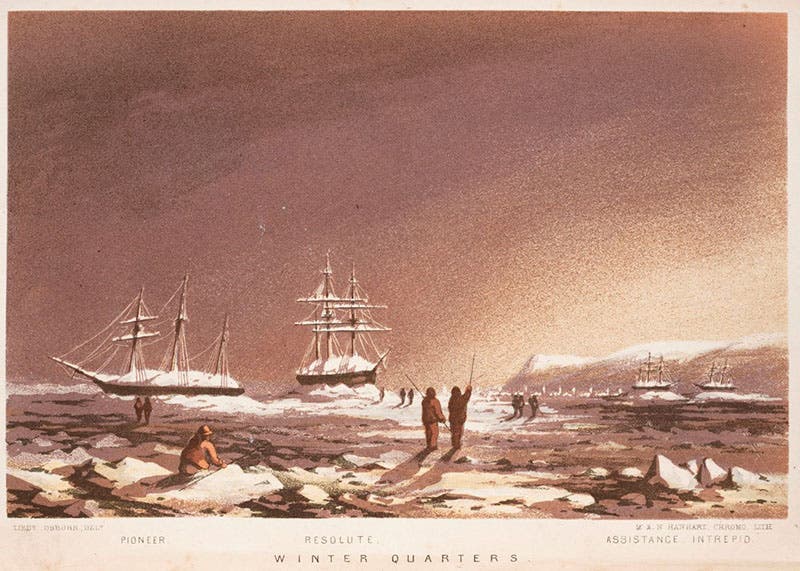

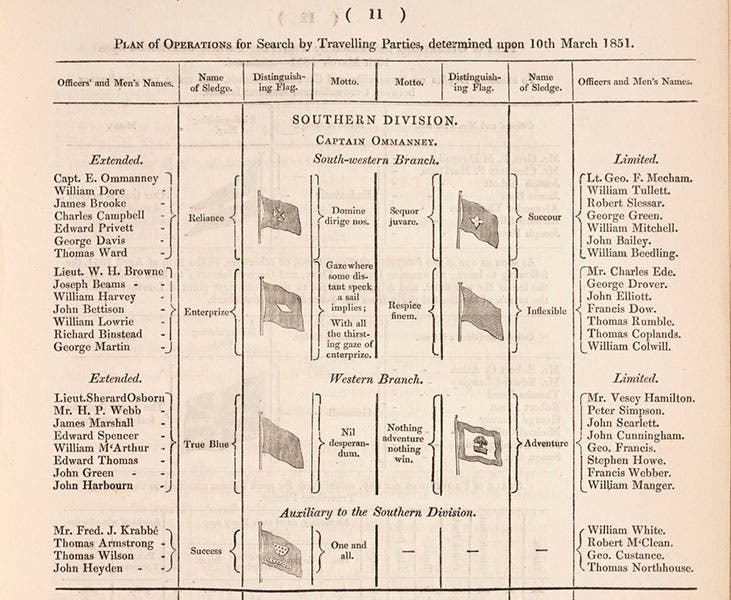

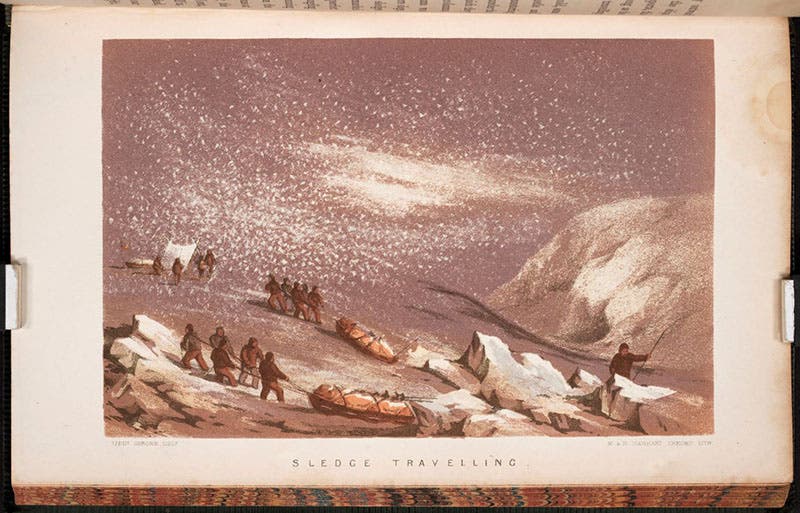

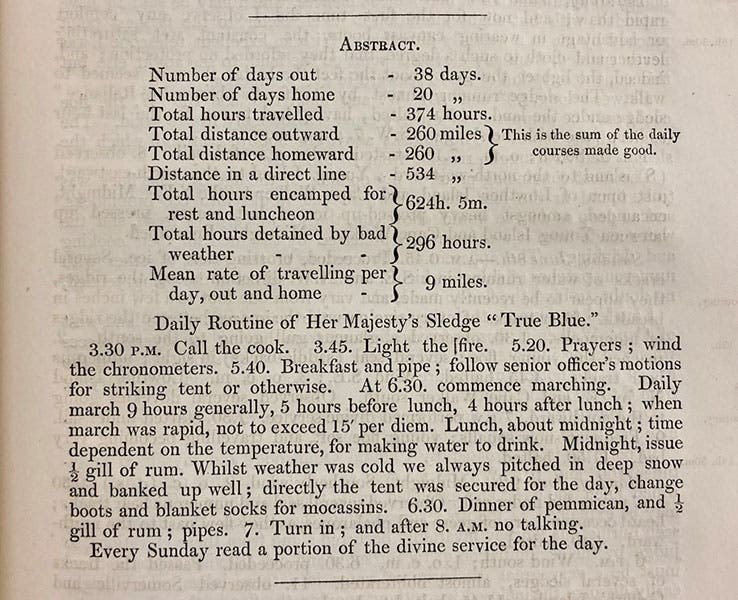

With the onset of winter in November, the ships were battened down near Griffiths Island, to await the thaw in May or June, when they would search again and then sail home (first image). But something new had been added to the British search repertoire on the Austin expedition: sledge parties. This was the idea of Francis McClintock, skipper of the other steamer, HMS Intrepid. Fourteen 400-pound sleds had been made in the London shipyards and brought along – each could carry about a thousand pounds of food and equipment, and they were man-hauled (the British had not yet warmed up to dogs), 7 men per sled, 200 pounds of haulage per man. The Royal Navy was typically formal about this, so each sledge had a name, a flag, and a motto. We see below (fifth image) the details for 7 of the sledges, with Osborn's sledge, HMS True Blue, having the motto "Nil desperandum," “never give up” (“HMS” now stood for “Her Majesty’s Sledge”). Come mid-April, all 14 sledges, in 8 parties, with most of the crew of the four ships, fanned out to the south, west, and north. The temperature was -50° when they left, and Osborn's sledge would be away from his home ship for 58 days and travel some 534 miles over the ice, as he later tells us in an official report in one of the Arctic Blue Books (seventh image) They mapped a lot of coastline, but of Franklin and his ships (which, we now know, were much further south), they found so sign.

Osborn wrote a stirring account of his part in the Austin expedition, with a delightful title: Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal, or, Eighteen Months in the Polar Regions: In Search of Sir John Franklin's Expedition, in the Years 1850-51. Osborn was very forthright in his opinions, especially about standard naval practices, of which he was often critical, which was probably why he never led an expedition of his own, although in the opinion of many, he was the best qualified of all. Three of our images for this post, and the map detail, come from Osborn's Stray Leaves. We used some of these same images in our post on Austin, since Austin did not publish his own narrative. The lithographs were based on drawings by Osborn himself.

The Austin expedition went home in 1851, but the next year, Edward Belcher set out with another squadron to continue the search, a flotilla that included Osborn and HMS Pioneer. They headed for the same general area, over-wintered, and sent out sledges, and it this case, found a ship – not one of Franklin’s, but HMS Investigator, which had attempted to come east from Alaska in 1850 and almost made it to Barrow Sound, before it froze in, permanently, at Mercy Bay om Melville Sound. It was discovered in 1853 by one of the sledge expeditions from the Belcher squadron and the crew was rescued.

The details of the accomplishments of Sherard Osborn’s sledge expedition with HMS True Blue, 1851, and a summary of their daily routine, in Additional Papers Relative to the Arctic Expedition under the Orders of Captain Austin and Mr. William Penny, 1852; note that they travelled at night and slept during the day (Linda Hall Library)

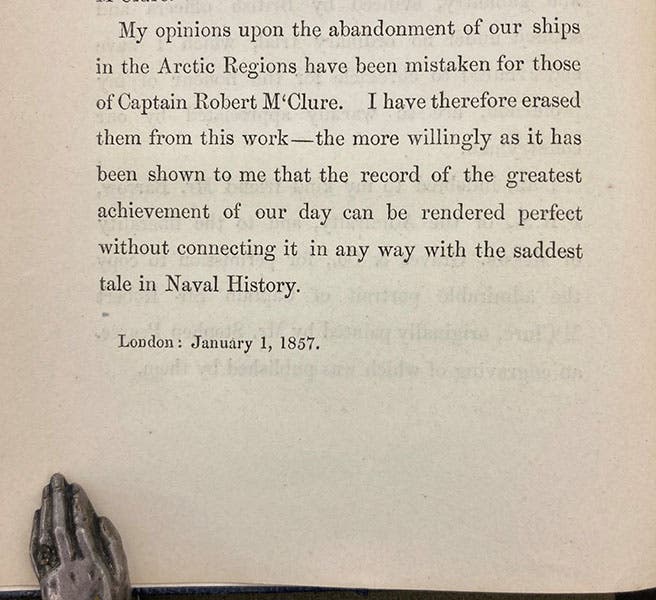

Belcher was more than a little incompetent, in the opinion of everyone except himself and the Admiralty, and the areas selected for overwintering were ill-chosen, so that the four ships were never freed from the ice in the spring of 1853. They stayed an extra year, hoping the ships would thaw out in the spring of 1854. They did not, so Belcher decided to abandon all four ships and take everyone home on the supply ship. Osborn and most of the other commanders were spitting mad – one does not abandon an entire squadron because of two overly-cold winters – and Osborn said so, loudly and often, orally and in writing. He did not publish his own narrative of the Belcher expedition, but he did write that of Robert McClure, the commander of the Investigator, the ship abandoned at Mercy Bay, whose rescued crew also went home on the supply ship (thereby becoming the first crew to make a complete Northwest passage, although not in the way intended). You can read more about the Investigator in our post on McClure. Osborn blasted the Belcher decision in this narrative of McClure’s expedition (1856). He was apparently taken to task for this, and the next year, he issued a second edition, in which he apologized and took out all the stuff about Belcher. But he still had his say. We reproduce here the last paragraph of his introduction, which ended with his calling the abandonment by Belcher of his ships "the saddest tale in Naval History."

Osborn is my favorite of all the Arctic explorers of the 1850s, although he is far less renowned than the more accomplished Francis McClintock, who later (1859) determined the fate of the Franklin expedition. I like Osborn because he called a spade a spade, and because he titled his narrative: Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal. How can you not like a guy like that?

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.