Scientist of the Day - Stefano degli Angeli

Stefano degli Angeli, an Italian mathematician and cleric, died Oct. 11, 1697, at age 74. Degli Angeli was a Jesuate, which can be spelled Gesuati or Jesuati, but NOT Jesuit, which is an entirely different order. I don't know how many excellent mathematicians the Jesuates turned out, but they had at least one other besides degli Angeli: Bonaventura Cavalieri, who in 1635 published a book called Geometria indivisibilius, which introduced a new method into mathematics – the method of indivisibles, which was a forerunner to the infinitesimals of calculus, would arise before the century had run its course. Degli Angeli was a student of Cavalieri, as well as being a fellow Jesuate. By the time he began writing his own books utilizing indivisibles, he was a professor of mathematics at Padua, occupying the very chair once held by Galileo. Indeed, Galileo helped Cavalieri obtain his professorship at Bologna, so degli Angeli and Cavalieri are often included as members of the “Galilean school” that was active after Galileo’s death.

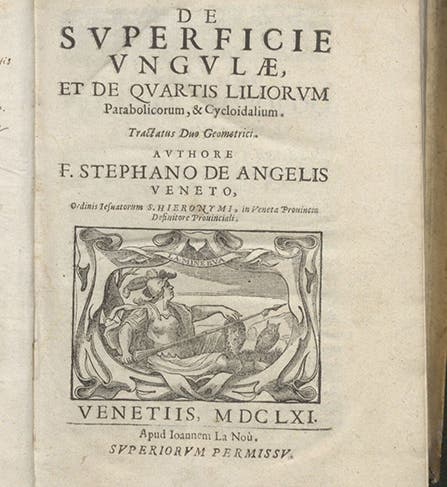

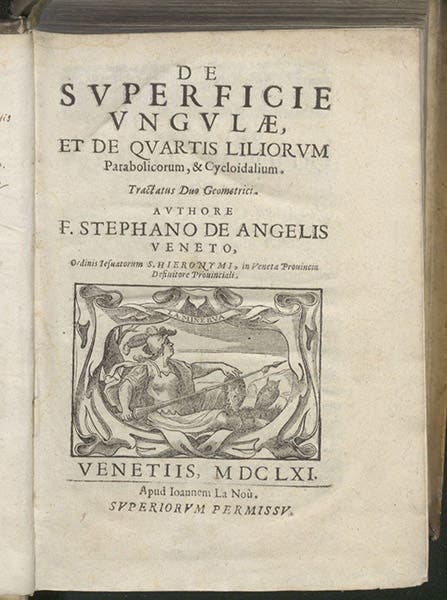

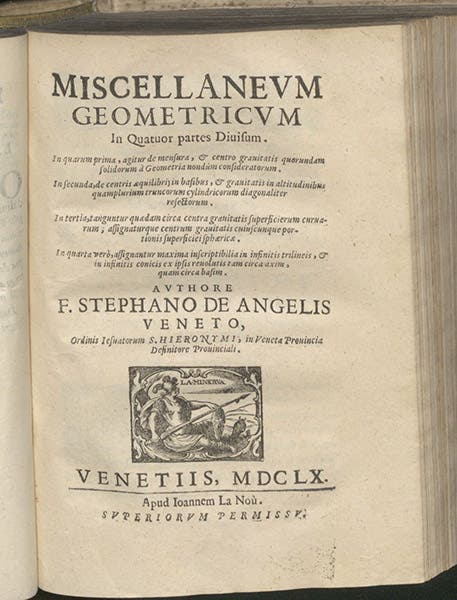

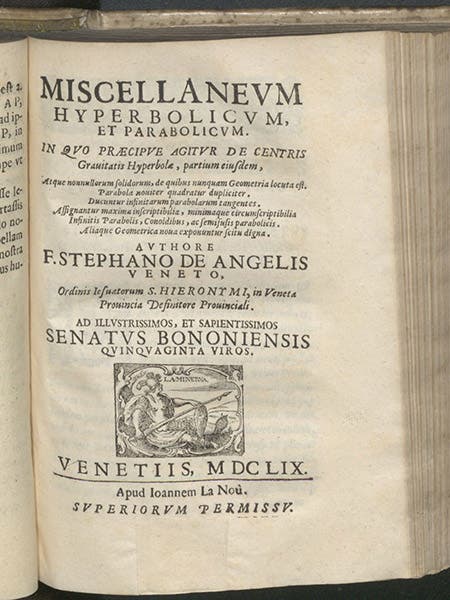

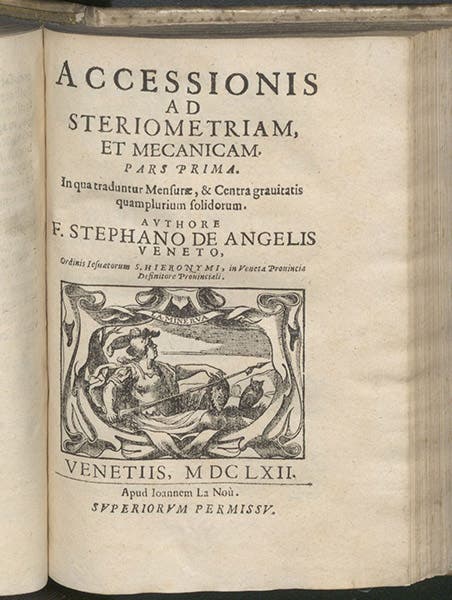

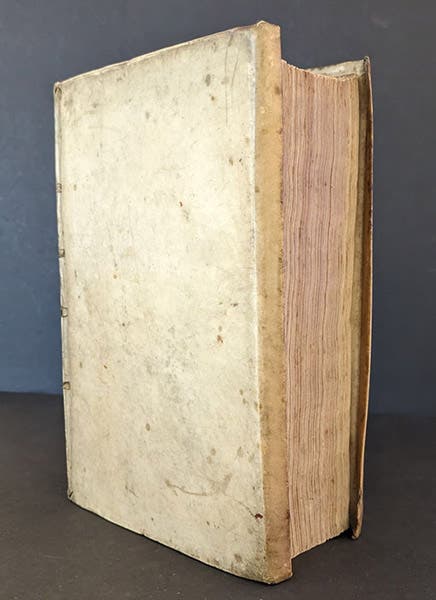

We have in our Library a beautiful sammelband of four works by degli Angeli, all published in Venice (where most Paduans published their books) between 1659 and 1662, and all the product of the same printer, Giovanni de Nòvo. Each of these pursues a set of geometrical problems, and each uses the method of indivisibles to help solve them. We show you the four title pages in the order in which they are bound, and you will see that they have a family resemblance, since all display the printer's mark of de Nòvo. The vellum binding is also of interest (third image), since it sports what would be called Yapp edges if it were a 19th-century book, where the limp vellum covers are folded over on the three free edges to protect the text-block. But this is a 17th-century, backed-vellum binding, and what they would have called it then, I know not. But it is a lovely thing.

Vellum binding with folded-over edges, and fore-edge of text-block, sammelband of four works by Stefano degli Angeli, 1659-1662 (Linda Hall Library)

Getting back to degli Angeli, he was the last of the Italian defenders of indivisibles. He was opposed by more powerful geometers, all of whom happened to be Jesuits, that is, members of the Society of Jesus, who had little use for indivisibles. Making matters even more difficult, the Pope suppressed the Jesuate order in 1668, although they had been around for over three centuries. Degli Angeli stayed on at Pisa as professor, but he was a Jesuate no longer, and he wrote no more about indivisibles, although he survived the death of his order by almost 30 years.

Almost 10 years ago, a historian of mathematics published a book, Infinitesimal (2014), in which he argued that the Jesuits opposed indivisibles for metaphysical reasons, because the implications of infinitely small entities threatened the traditional world order of Aristotle, into which infinitesimals did not fit. The author also suggested that the Jesuits were behind the abolition of the Jesuate order, as a way of attacking the two most prominent defenders of indivisibles (one of which, however, had been dead for 20 years). I am willing to believe that the Jesuits conspired against degli Angleli. But I would guess that the reasons were far more petty than protecting the traditional world order. And it seems more probable to me that the Jesuates were dispersed because of certain moral lapses (the traditional explanation) than because they believed that a line is composed of infinitely small indivisibles.

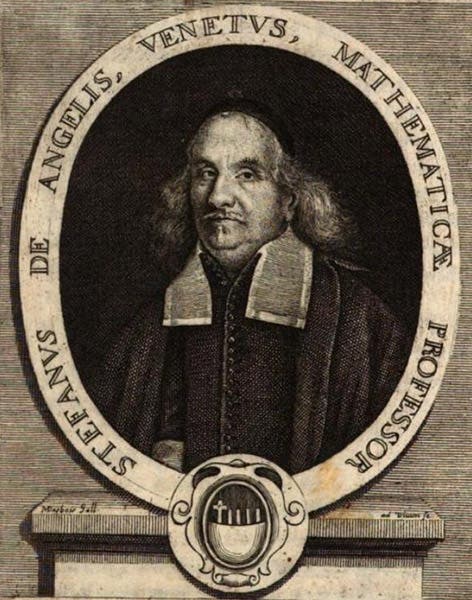

There is only one portrait of degli Angeli, which comes from a portrait book of famous professors at Padua, published in 1682. We do not have this work, and we show you a second-hand version from Wikipedia (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.