Scientist of the Day - Stephan Blankaart

Stephan Blankaart, a Dutch physician and student of insects, was born in 1650 in Middelburg and died on Feb. 23, 1704, in Amsterdam. He grew up in Middelburg, where his father was a schoolteacher and later professor, and Stephan went on to receive his medical degree in Franeker. Blankaart tells us (in the book we will discuss shortly) that as a young lad, he was interested in nature, especially insects. The principal authority on insects when Blankaart was growing up was Johannes Goedaert, who wrote and published a three-volume illustrated compendium on insects, especially butterflies, called Metamorphosis et historia naturalis insectorum (1660-69). Goedaert also lived in Middleburg, although he was 30 years older than Blankaart, and since we know that Blankaart went to Latin school with the best friend of Goedaert's son, it is likely that the older Goedaert and the young Blankaart encountered each other before Blankaart headed off to medical school. Certainly Blankaart refered to Goedaert numerous times in his own book on insects.

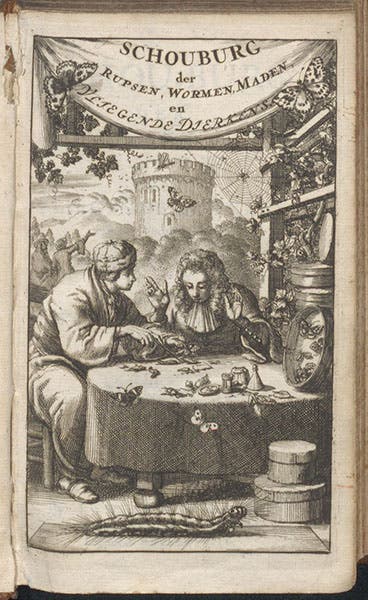

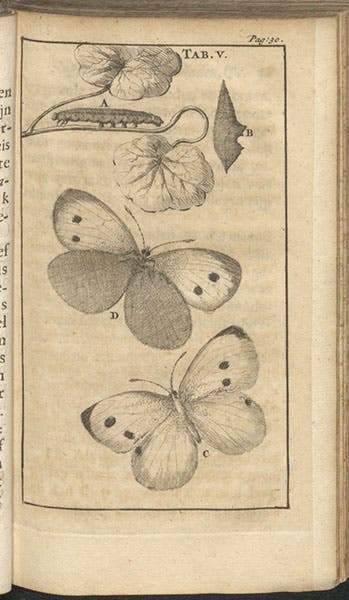

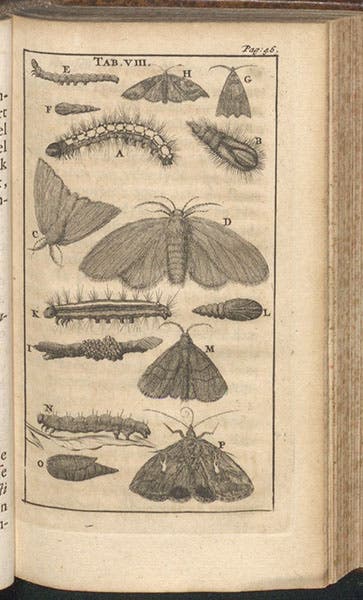

Blankaart published several works on anatomy, and a medical dictionary, before he got around to publishing his insect studies. But his Schou-burg der rupsen, wormen, máden, en vliegende dierkens daar uit voortkomende (Theater of caterpillars, worms, grubs, and the flying animals that arise from them) finally appeared in 1688. We have a fine copy in our collections. The text is in Dutch, but the abundant engravings, many of them folding, speak a more universal language. Like Goedaert, Blankaart had a fondness for butterflies, moths, and their caterpillars, but he also included plates that show mites, weevils, arachnids, and even sliced-open plant galls with their insect nurseries inside. Blankaart was a fine artist – many of his drawings survive – and the engravings contain very realistic depictions of such butterflies as the three we include here.

An engraved frontispiece provides an attractive introduction to the book. We guess that it depicts Blankaart (without his wig) at the left, showing some features of caterpillars to an astonished burgher, who throws up his hands in amazement. We show a detail of the central scene as our first image, and the entire engraving as our third. The red admiral on the front of the tablecloth is very similar to the red admiral that we showed in our post on Goedaert. The other butterfly up front, the white cabbage butterfly, is the subject on one of Blankaart's own engraved plates (fifth image).

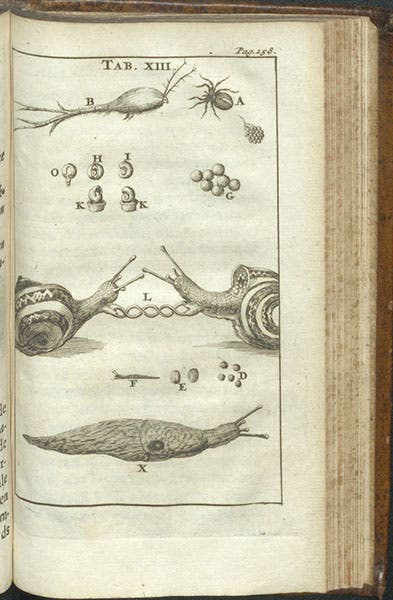

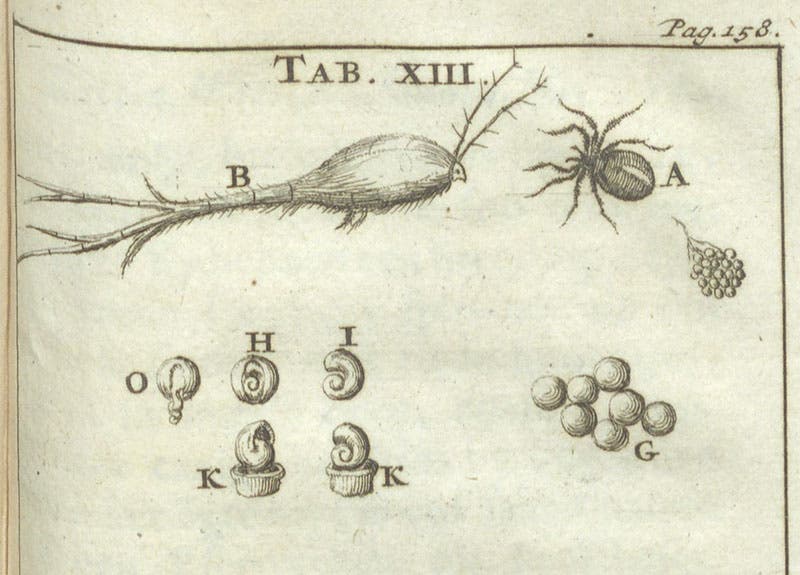

One of Blankaart's engravings, which has nothing to do with butterflies, is a milestone to a very small and select group of entomologists who call themselves copepodologists (those who study copepods). Copepods are tiny (microscopic) crustaceans, sometimes known as 'water-fleas', which are found in both seawater and freshwater. Blankaart found some of the freshwater kind in a well, studied them, and on one of his engraved plates, provided the very first printed picture ever of a magnified copepod (seventh image). You would probably not even notice it, mesmerized as you might be by the copulating snails in the center, but if I crop them off (eighth image), you can now focus on the copepod, which is figure B. It is not a great likeness, but with its long forked tail, the two appendages on its head, and its one eye, it is unmistakably a copepod. Blankaart probably observed it with a magnifying glass or a single-lens microscope, similar to those depicted on the engraved frontispiece; there is no compound microscope in sight. It would appear to be a member of the genera Cyclops, the one-eyed copepods. To see some other copepod illustrations, ones that benefited from 150 years of improvements in microscopes, see our post on Louis Jurine.

A Dutch scholar, Kees Beaart, has published several short pieces on Blankaart, just about the only studies done of Blankaart’s insect work, and he was kind enough to send me both. Google Translate was kind enough to render these (in a manner of speaking) from Dutch to English. Dr. Beaart had earlier helped me with my post on Goedaert, on whom he is the world’s foremost authority. He tells me that Blankaart completed a Part Two for the Schou-burg der rupsen, which was not published, but the manuscript for which survives in the Royal Library in Amsterdam. Since the images in the manuscript are original watercolors by Blankaart, it would be nice if some academic publisher would take an interest and give us both a facsimile and a printed version, and perhaps a translation.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.