Scientist of the Day - Thomas Pennant

Thomas Pennant, a Welsh naturalist, traveler, and inveterate letter-writer, was born June 25, in Downing, Flintshire. He would live at the family estate in Downing for his entire life, when he wasn’t travelling and collecting. Pennant wrote a large, illustrated, 2-volume work on British mammals and birds in 1766, a History of Quadrupeds in 1781, and a book on Arctic (i.e., American) zoology in 1784, all of which we have in our library (the Quadrupeds in a third edition). We discussed two of these in our first post on Pennant.

Pennant also wrote, and received, letters from a variety of naturalists, such as Peter Simon Pallas. Another correspondent was Gilbert White, whose Natural History of Selborne contained many of White’s letters to Pennant, as we pointed out in our post on White. Pennant also like to travel, although he tended to limit his travels to the British Isles. He toured through Wales, and up into Scotland (twice). When he returned, he wrote and published accounts of each of his journeys. We have only one of these, A Tour in Scotland, and Voyage to the Hebrides; MDCCLXXII (1774-76), an account of his second trip north. It is this book that we will feature today.

Pennant's Tour of Scotland is actually more of an antiquarian work than a book of natural history, since Pennant was fascinated by ruins, and he had his artists capture and then engrave nearly every antiquity he ran across. The most prominent exception to this antiquarian emphasis is a description in volume 1 of the geology of the isle of Staffa in the Scottish Hebrides, complete with numerous engravings.

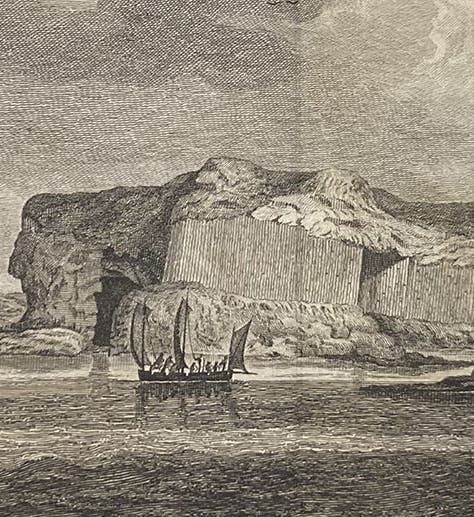

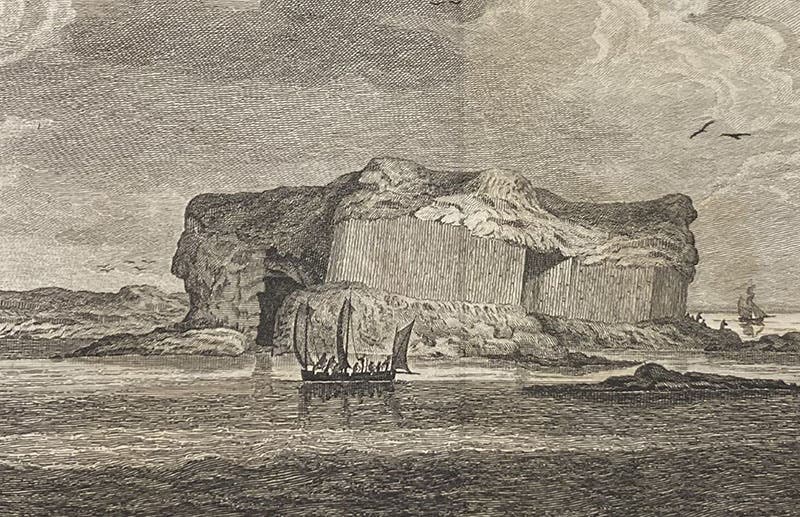

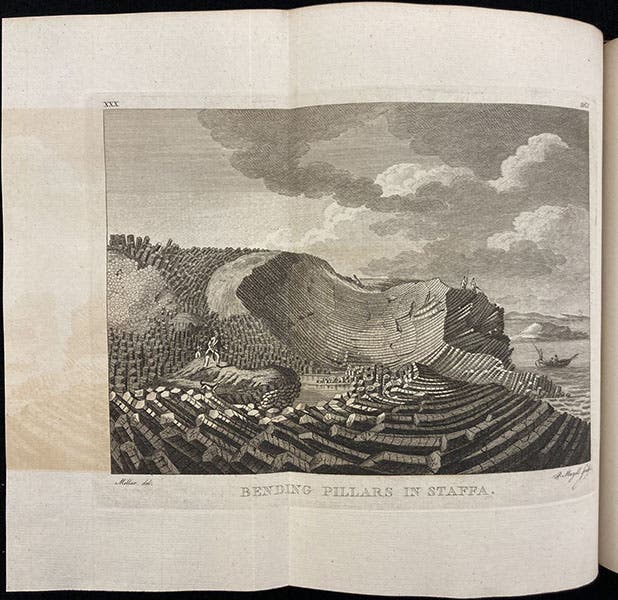

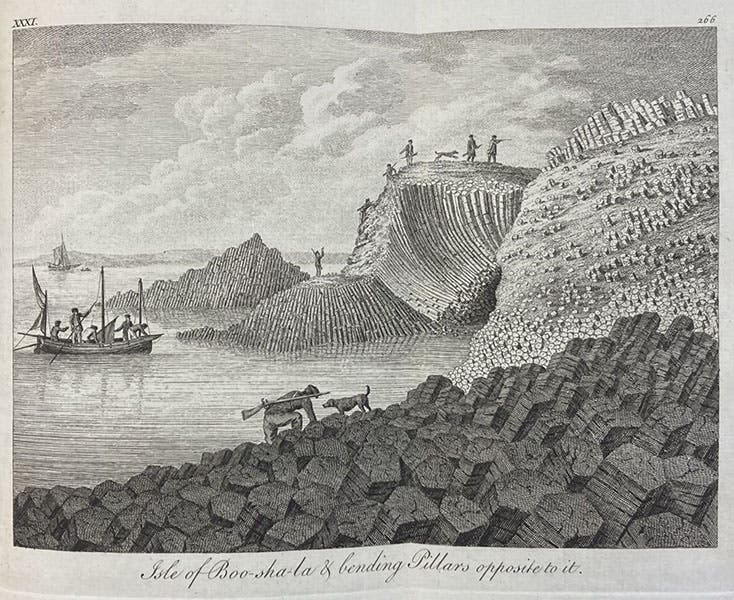

The odd thing about the section on Staffa, which is certainly the most famous and most often reproduced part of his book, is that Pennant did not write it, nor did his artists illustrate it. He planned to make the sea journey to Staffa from Mull, but bad weather prevented it, so he himself never got to see the soon-to-be famous Fingal’s Cave. Fortunately, Joseph Banks, on a trip to Iceland the year before, had stopped at Mull when the weather was better, was able to take a boat to Staffa, and bring along his artist, James Miller, who drew the island, Fingal’s Cave, and the striking basalt pillars on nearby Boo-Sha-la. Banks generously let Pennant use his observations and Miller’s five drawings, and Pennant had the drawings engraved for his book. We show three of them, either entirely or in a detail, in this post. We included these and the other two in our post on Banks 9 years ago, but the reproductions there are not as good as those here.

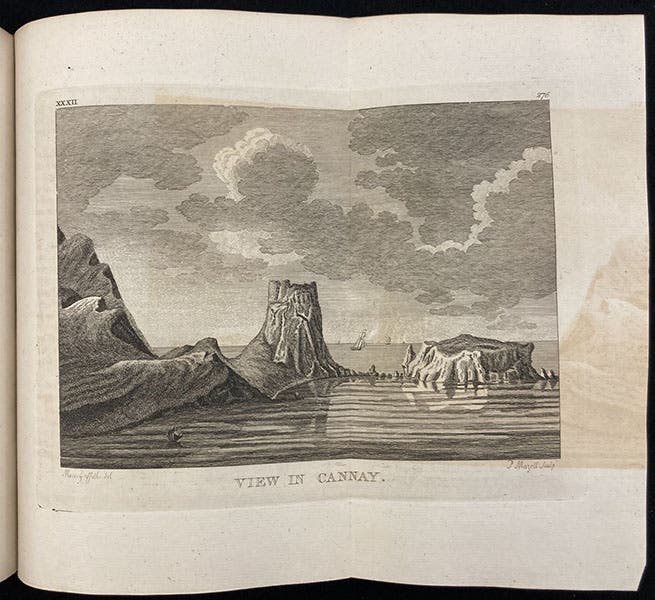

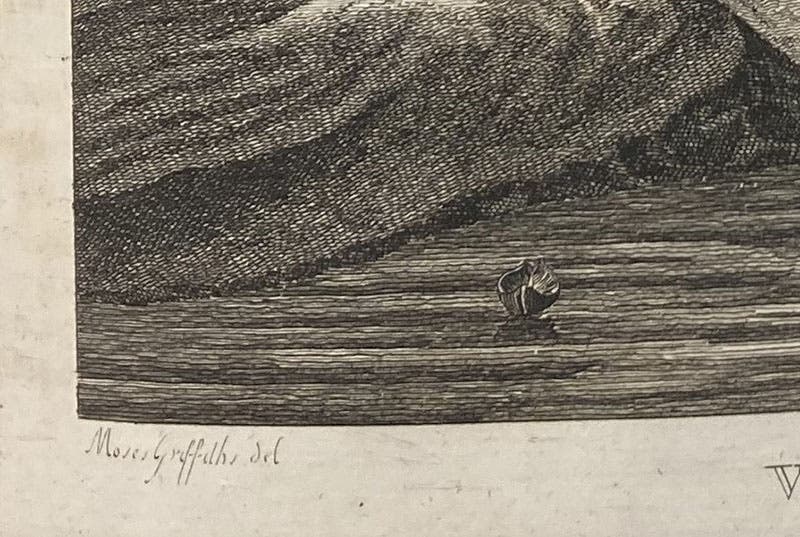

One of the engravings we show here, “View in Cannay,” was not made from a Miller drawing, but from a sketch by Pennant’s own artist, Moses Griffith. We happen to have in our library a portfolio of original watercolors by Griffith, whom we featured in a post some years ago. We include here not only the engraving, but also a detail of Griffith’s signature, since he doesn’t get nearly the recognition he should.

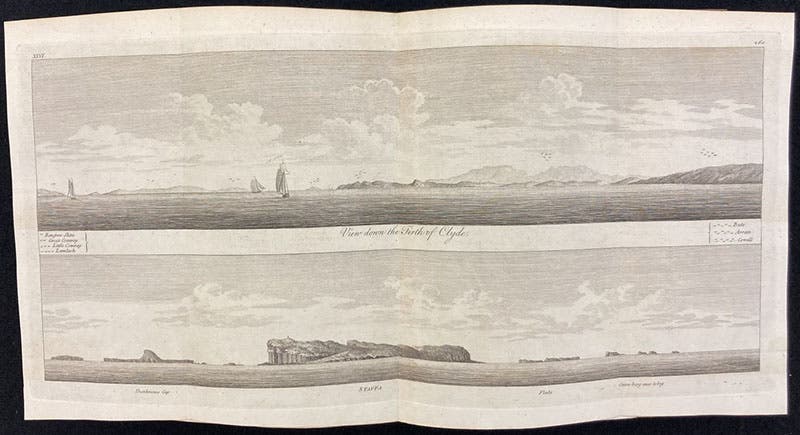

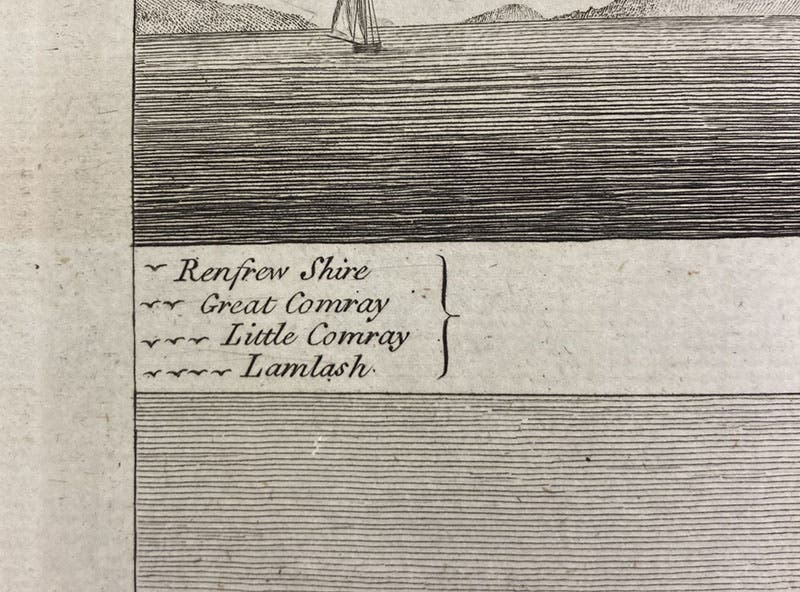

I also wanted to show you a double-page fold-out engraving that displays two panoramic views, one of the Firth of Clyde at top, and the other of Staffa and its surrounding islands (ninth image). I like this engraving because of the way the islands are identified. Not wanting to ruin the view with labels or numbers, the artist inserted small flocks of birds, each flock with a different number of birds, near each island (see detail, tenth image), and then provided a key at the left: 3 birds is Little Camray, 4 birds is Lamlash, etc. (eleventh image). Each scene remains unsullied by conventional labels. I have seen bird identifiers used this way only one other time, in George Poulet Scope’s Memoir on the Geology of Central France (1827). You can just make out the key to the bird identifiers at the top of images 1 and 2 in our post on Scrope.

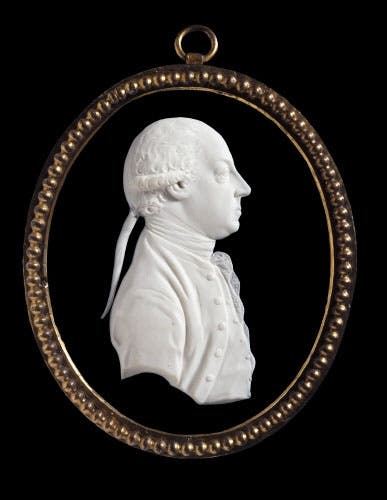

In our first post on Pennant, we showed an engraving, after the portrait of Pennant by Thomas Gainsborough in the National Museum of Wales. For this occasion, we show a ceramic medallion portrait fashioned by Josiah Wedgwood I sometime after 1775, which is in the British Museum (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.