Scientist of the Day - Ursula Le Guin

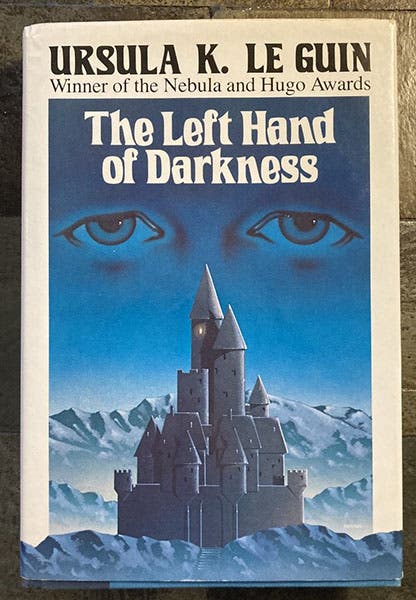

Dust jacket of The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula Le Guin, Harper & Row edition, 1980 (author’s collection)

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin, an American science fiction author, was born Oct. 21, 1929, three days before the New York Stock Exchange awoke to Black Tuesday. Fortunately, academic Berkeley was about as far as you could get from Wall Street, and Le Guin's childhood seems to have been relatively unaffected by the depression. Her father was a well-known anthropologist, Alfred Louis Kroeber, and her mother was a writer. Le Guin's own studies were interrupted by her marriage in 1953 to a historian, and she turned to raising a family and writing when she could. Her first work was published in 1959, and she continued writing and publishing through the 1960s, with little notice taken by the reading public.

Then, in 1969, Le Guin published The Left Hand of Darkness, a feminist science fiction novel – really the first feminist SF novel – and readers and critics were amazed, aghast, and, in the end, full of applause. The book is about a human envoy who visits the planet Gethen with hopes of persuading the two nations of Gethen to join the Ekumene, a federation of planets. What drives the plot is the fact that the people of Gethen are androgynous, taking on both masculine and feminine roles, with everyone capable of bearing children. The male envoy, Genly Ai, finds himself incapable of understanding and socially interacting with a people when gender is taken out of the equation. The story is intricate, and we will not attempt further exegesis here. But the book is compellingly readable, which is remarkable, given the fact that the story moves along slowly and relatively undramatically. Le Guinn was a truly masterful writer. And she used the science fiction genre not to examine the future, but rather the present. The Left Hand of Darkness is really about the late 1960s and the growing realization that gender equality in the United States was a long way from being realized.

The Left Hand of Darkness is considered by many – certainly by me – to be one of the great SF novels of the last third of the 20th century. It has taken some abuse from a few feminist critics, who have objected to the use of masculine pronouns in describing the people of Karhide, one of the nations of Gethen. And Le Guinn herself later expressed regret about this. But the book appeared in 1969, after all, not 1999, so it is a bit unfair to impose later standards on such an early product of the feminist movement. And most literary critics today have no problem seeing beyond this in appreciating the significance of Le Guin’s work.

Le Guin wrote some 20 novels and scores of short stories. I have not read any novels except The Left Hand of Darkness, so I cannot and should not comment on them. But I have read many of her short stories, and I thought I would mention one that I just loved when I first read it in graduate school, and still do. I am going to spoil it for those who might want to read it, but there is no way I can tell the story without the reveal. It is called “Schrödinger's Cat,” and I first ran across it in an anthology, Universe 5 (1974), edited by Terry Carr, who was one of Le Guinn's editorial champions in the early 1970s. The story takes place in the narrator’s house, as she finds she has been joined by a strange cat. Soon after the cat appears, the narrator answers the doorbell, to find a dog-like creature bearing a huge knapsack, within which is a box, and a photon gun. The dog sees the cat, and recognizes it as Schrödinger's cat, and proceeds to tell the narrator about Schrödinger's thought experiment, as he sets up his equipment. If a cat is sealed in a box with a photon gun, whose emitted light particle might or might not result in the death of the cat, the laws of quantum mechanics say that the cat is neither alive nor dead until it is observed. So when you open the lid of the box, you either kill or save the cat. The dog sets up the experiment, the cat obligingly jumps in and closes the lid with its tail, and the narrator tries to decide what to do. At that moment, something removes the roof of the house.

Ursula Le Guin continued to be productive and socially active until her death in 2018. She won every award it was possible to win, and refused a few when her refusal would make a statement that she thought should be made. The PBS series American Masters did a program on Le Guin just after her death, in 2019, which is well-worth seeing. I could not find the show online, but those of you who support public television might have access to the archived program, which is described here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.