Scientist of the Day - Wang Yirong

Wang Yirong, a Chinese scholar, died Aug. 14, 1900, at the age of about 55. We know little of Wang's life, except that he was a director of the Chinese Imperial Academy, and a calligrapher of some skill. He was caught up in the Boxer Rebellion of 1899, a movement to expel all foreigners from China, reluctantly accepted a position as a commander, and then on this date in 1900, committed ritual suicide with his wife and family.

A year prior to his death, Wang made a discovery that would completely change the study of ancient Chinese history. He acquired some "dragon bones" from a pharmacist. Dragon bones were a long-standing Chinese remedy for a variety of illnesses and were ground up by pharmacists and sold as medicine. But the bones Wang acquired were unground, still intact, and they were covered with written symbols that, to Wang, resembled rudimentary Chinese characters. He sought the original location of the bones from the pharmacist, who, feeling his livelihood threatened, refused to reveal his sources. Nevertheless, Wang collected bones from other pharmacists and tried to translate them. And then Wang died his sad death. Fortunately, a friend and colleague, Liu E, continued to collect dragon bones, recording the characters inscribed upon them. Liu published the first paper on dragon-bone characters in 1903, arguing that the bones contained records of the oldest Chinese writing. He, and Wang, turned out to be correct.

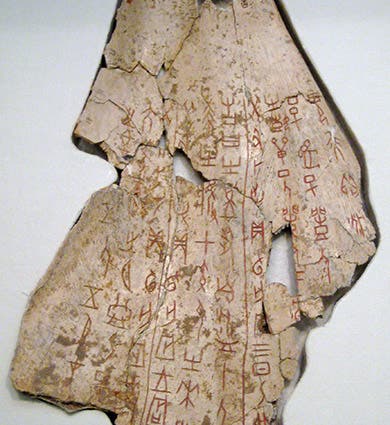

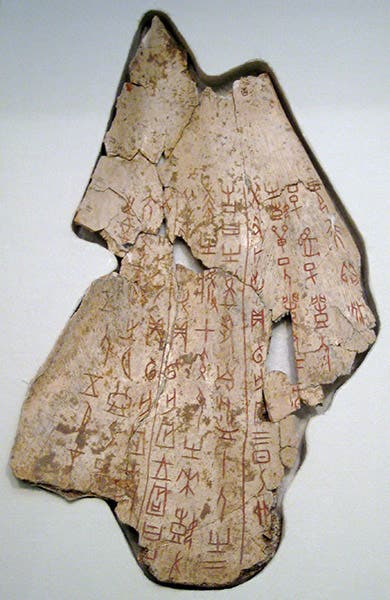

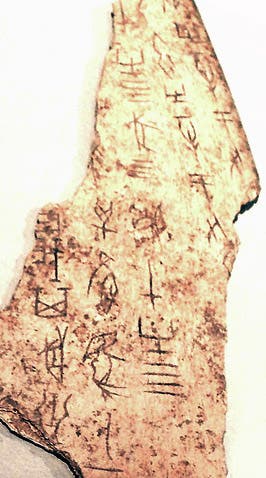

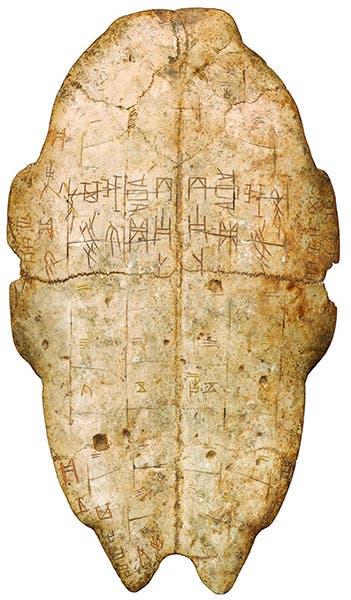

It was not until after the deaths of both Wang and Liu (in 1909) that the dragon bones were traced to Yinxu, a site near Anyang in northern China, which was once the capital of the Shang dynasty (ca 1600-ca 1045 BCE). Further research has revealed that the bones, which consist primarily of either ox scapulae (shoulder bones) or turtle plastrons (flat belly shells), were oracle bones, with questions written upon them. The diviner would hold the bones over a fire until they cracked, and then "read" the cracks as they cut through the written questions. Hundreds of thousands of them have been found in excavated oracle bone pits, and they contain an immense amount of information about the latter stages of the Shang dynasty. In fact, they contain our only written information about this period, except for the Records of the Grand Historian Sima Qian, written a millennium later. So just before he died, Wang managed to become the father of Chinese linguistic archaeology, even though it took a little while for that discipline to establish itself.

There are quite a few collections of oracle bones in both China and the West. We show here two examples of ox scapulae inscribed with late Shang dynasty script (first and third images). We also show an inscribed turtle plastron (fourth image), as well as an oracle bone pit found at Yinxu, Anyang, with hundreds of turtle plastrons that had been heated, cracked, and used for divination (fifth image). This Cambridge University webpage shows an ox scapula in 3-D at the right, which you can rotate to see front and back from all angles, once you master the proper mouse-and-wheel movements. In nearly every library that holds oracle bones, they are the oldest specimens of writing in those libraries.

There survives just one photographic portrait of Wang (second image). If you search Google Image for Wang Yirong, the images that come up most often are pieces of calligraphy. Wang was apparently a master of the art, and specimens of his work still sell regularly at auction. Here for example are a pair of Wang Yirong scrolls that were auctioned at Sotheby’s in 2018 (you can zoom in on these at the link). The hammer came down at $10,000 US. It is pity that Wang did not enjoy fame or profit in either archaeology or calligraphy during his lifetime.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.