Scientist of the Day - William Allen Miller and William Hallowes Miller

William Hallowes Miller, a Welsh crystallographer and mineralogist, was born Apr. 6, 1801. He attended St. John's College, Cambridge, where he succeeded William Whewell in 1832 as professor of mineralogy. William Allen Miller, an English chemist, was born in Ipswich on Dec. 17, 1817. He attended King's College, London, where he succeeded John Daniell as professor of chemistry. In the 1840s, both men did pioneering work in spectroscopy, and they are the most significant workers in that field between Joseph Fraunhofer in 1817 and Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen in 1859. William Hallowes did most of his important work in crystallography and in the establishment of new British standards of weight and measure, neither of which we have the competence to discuss here. William Allen stuck with spectroscopy and made several important contributions to the field, and these will be the focus of our discussion today. So we are in the odd position of using the occasion of William Hallowes Miller’s birthday to explain the achievements of William Allen Miller. But this will also help us make the point that, when one discusses the William Millers of Victorian science, one damn well better include middle names, or at least middle initials. Many have not done so, and as a result, the achievements of the two Millers are often confused.

In 1817, Joseph Fraunhofer, an astronomer in Munich, announced that the solar spectrum (the long-drawn-out rainbow that you see when you send sunlight through a prism) contains hundreds of transverse dark lines. He published a black-and-white engraving showing the position of these lines, labelling the more prominent lines with Roman letters - A, B, C, D, etc. But he did not know why the lines were there, or what they told us about sunlight or the Sun. You can see the original engraved Fraunhofer spectrum at our post on Fraunhofer.

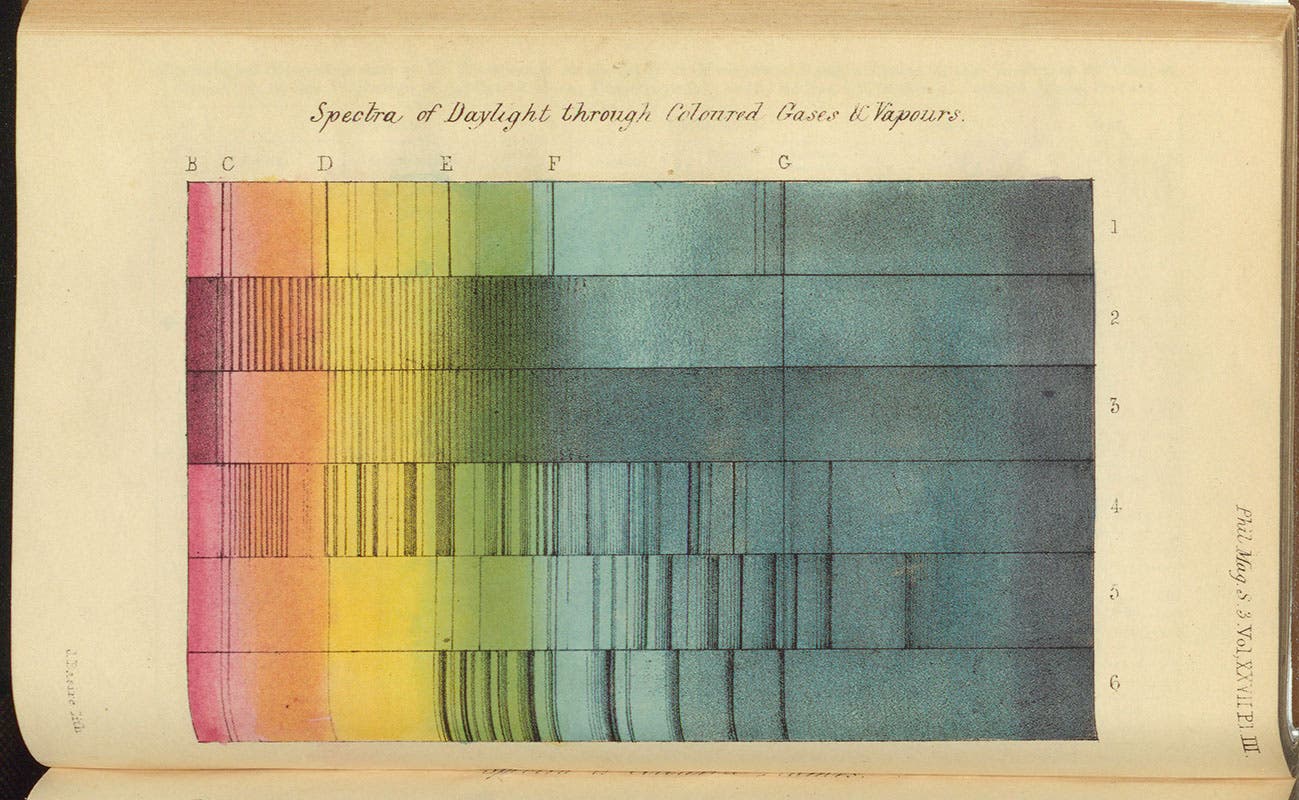

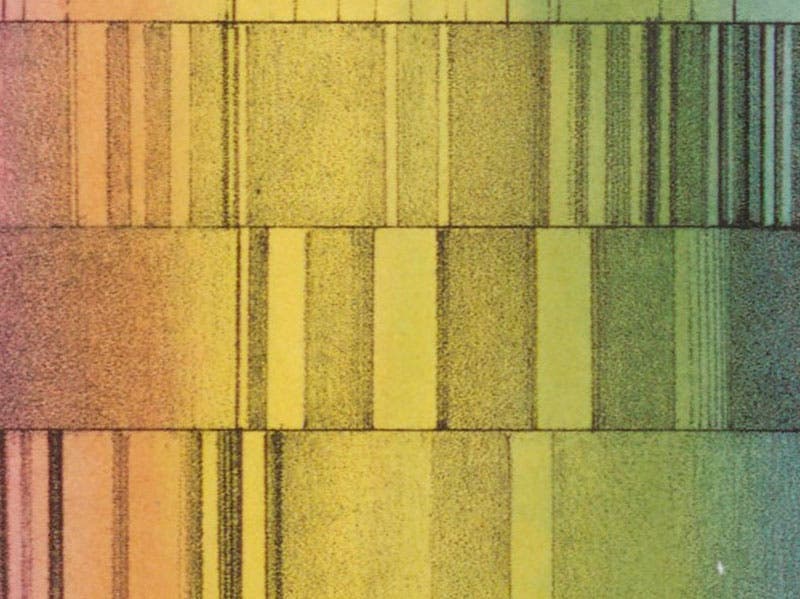

In 1845, William Allen Miller read a paper, "Experiments and observations on some cases of lines in the prismatic spectrum," to the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) at Cambridge (William Hallowes' home institution), which was then published in the London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine (often referred to as just the Philosophical Magazine). He revealed that you could create Fraunhofer-like spectral lines in the chemical laboratory, by sending light through the vapors of various elements and compounds, such as iodine, bromine, or copper chloride. You could also produce lines, bright ones this time, by burning elements or compounds in an alcohol flame. He mentioned that he was building on the prior work on iodine and bromine of David Brewster, John Daniell, and William Hallowes Miller. He referred to William Hallowes as “Prof. Miller from Cambridge.”

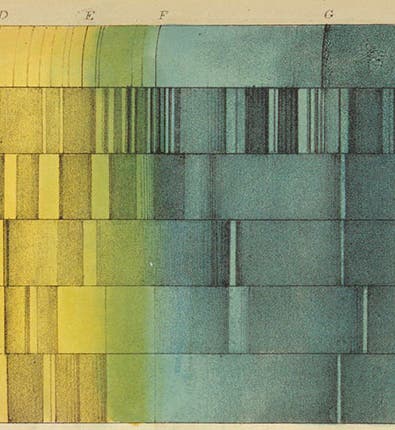

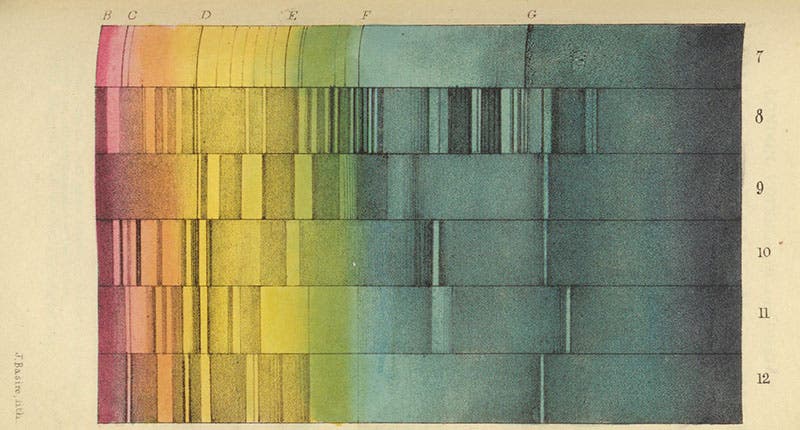

Miller illustrated his printed paper with two beautiful chromolithographed plates by the inimitable James Basire III. We show both plates here (first and fourth images); each of them has a Fraunhofer solar spectrum at the top, with the prominent lines marked, indicating (as the text did as well) that Miller was well aware of the connection between his chemical spectra and the Fraunhofer lines in the solar spectrum. We also show a detail of the second plate (fifth image). One might think that lithography would not be the ideal medium for delineating a precise series of lines, but, as Miller tells us, his lines were anything but precise, and he was just trying to convey a general impression of what one sees in chemical spectra. Lithographs had one great advantage: they could be printed in color, while line engravings could not.

Building on the work of both Millers, Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen then undertook a much more detailed study of the spectra of chemical elements and compounds, utilizing the advantages provided by the much hotter and cleaner flame of the Bunsen burner. They published their results, with their own chromolithographs of chemical spectra, in 1860; we showed those lithographs in our post on Kirchhoff as well as our post on Bunsen.

Kirchhoff and Bunsen are usually credited with founded the science of spectroscopy, but William Allen Miller, and to a lesser extent, William Hallowes Miller, deserve more credit than they commonly receive for anticipating and setting the stage for the work of Kirchhoff and Bunsen.

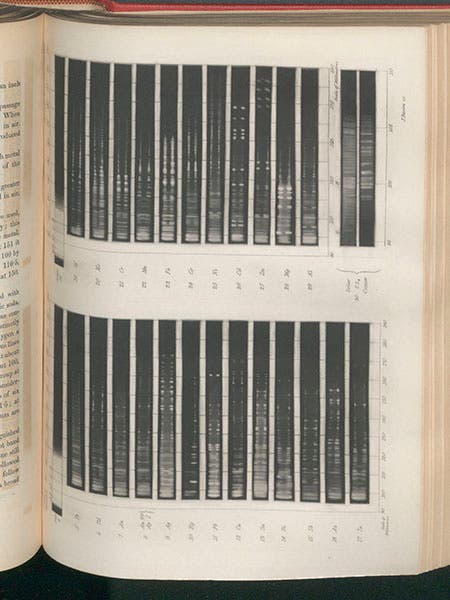

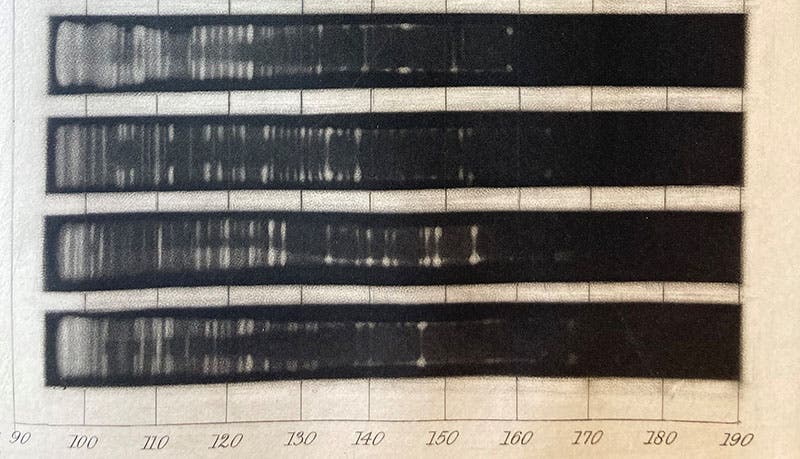

One year after Kirchofdf and Bunsen published their landmark paper, William Allen Miller made another important contribution to the science of spectroscopy, this one quite original – he succeeded in photographing a series of chemical spectra in the lab, using an ingenious spark chamber of his own design. The sparked gases produced light which was sent through a prism and then onto a photograph plate, where the spectral lines were recorded. Miller showed his photographs to the BAAS meeting in Manchester in 1861, and then published his paper in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1862. There was no way to print photographs directly at that time, so Mr. Basire produced mezzotints that admirably conveyed the appearance of the tiny spectra photographed by Miller (sixth and seventh images).

William Allen Miller continued to work in spectroscopy, soon joined by William Huggins, both of whom were rewarded for their work in 1667 by the Royal Society. Miller died prematurely at age 53, in 1870. His semi-namesake William Hallowes Miller continued to work on reestablishing the British standards of weights and measures (all the British standards had been destroyed in the Parliament fire of 1834) until his own death in 1880, at the age of 79.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.