Scientist of the Day - William Baffin

William Baffin, an English pilot, died Jan. 23, 1622. Of all the great navigators, Baffin is the one we know least about. He suddenly appeared on a ship's roster in 1612, and we have no idea where or when he was born or what kind of upbringing he had. But the ten years of his life that we do know about are filled with both adventure and accomplishment. Between 1612 and 1616, Baffin served as pilot on five voyages to Arctic regions along both the eastern and western coasts of Greenland. The first three were to the area of Spitsbergen, as part of whaling expeditions sponsored by the Muscovy Company, in an attempt to find a Northwest Passage to the Orient. On these voyages, Baffin demonstrated his considerable navigational skills, which involved taking difficult astronomical observations at sea.

Baffin then entered the services of the Company of the Merchants Discoverers of he North-West Passage, which was well funded by sponsors including Sir Thomas Smith and Sir Dudley Digges. The Northwest Passage Company, as we shall call it, had already sponsored three voyages exploring in the area of Davis Strait west of Greenland, one of which included Henry Hudson, who discovered the strait and bay named after him, and who was then cast adrift by his rebellious crew, to be seen no more. The ship used by Hudson, called the Discovery, was a tiny flyboat of 20-tons displacement, which had been built in 1602, and was one of the three ships that ferried colonists to Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. When the Discovery returned without Hudson, the Northwest Company sent it out twice more under other captains, to explore Hudson Bay, but without finding a passage. Not ones to give up easily, in 1615, the Company sent out the Discovery again, and this time, Baffin was aboard as pilot, and Robert Bylot (who had been on Hudson’s last voyage) as captain.

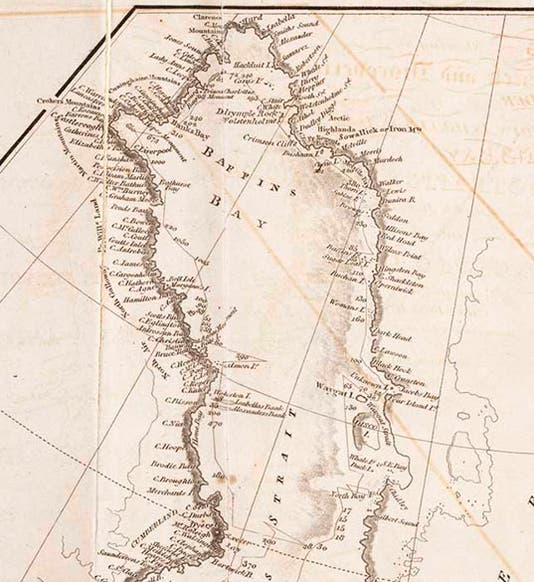

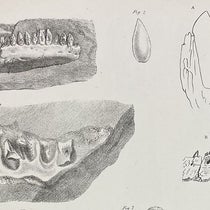

The 1615 expedition returned to Hudson Strait and Hudson Bay, and for this voyage, we have tangible evidence of Baffin's map-making skill, as a single map survives in his own hand depicting Hudson Strait and the eastern entrance to Hudson Bay (second image). Clements Markham reproduced it in his 1881 book about Baffin (which is not in our Library); I do not know if the original map survives, and if so, where it might be.

It was also on this voyage that Baffin made the first attempt ever (as far as we know) to determine longitude at sea, using what is called the "lunar distance" method, which involves measuring the angular distance between the Moon and a star, and then the altitudes of both the Moon and the star. Usually this involves comparing the readings to a set of tables to establish local time. I do not know what Baffin used for tables, since the method, while invented in the early 16th century, had never been used before at sea. But historians of navigation and of longitude determination have long been very impressed by Baffin's accomplishment.

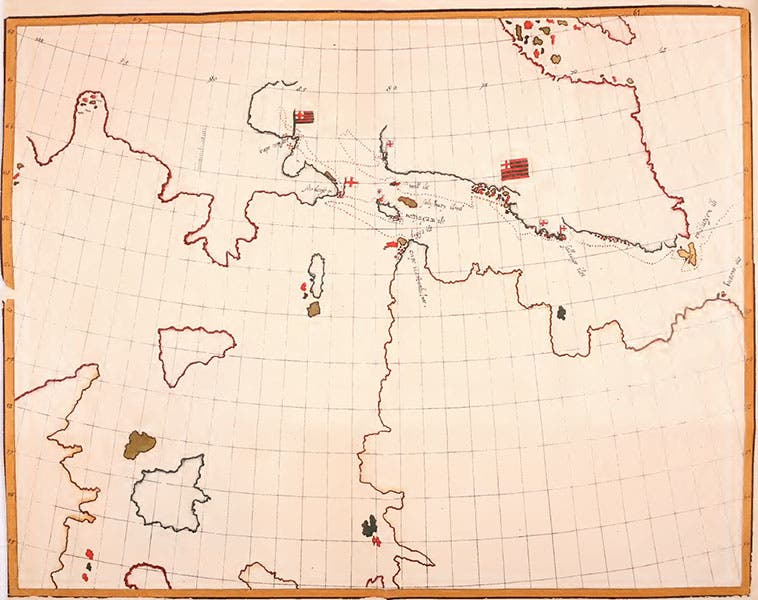

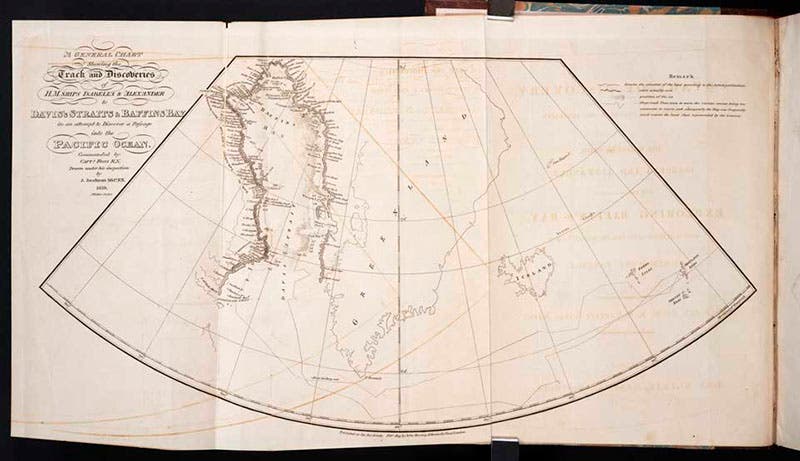

The 1615 voyage, while producing one surviving map (and presumably many other maps) of great accuracy, did not yield any sign of a Northwest Passage, so Bylot and Baffin were sent out again in the Discovery in 1616, this time to explore up Davis Strait, which had been discovered by Englishman John Davis in 1586, and which extends north of the entrance to Hudson Strait. Although the sea north of Davis Strait (now called Baffin Bay) was clogged with ice, the Discovery managed to explore both coasts, that of Greenland on the east, and what is now Baffin Island on the west. At the north end of the bay, they found three sounds, which they named after three of their patrons: Lancaster Sound, Smith Sound, and Jones Sound. All of these were blocked by ice, so Baffin and Bylot were unable to discover that Lancaster Sound, which led to the west, was indeed an avenue into the Arctic archipelago and the beginning of a Northwest Passage, as William Parry would discover 203 years later,

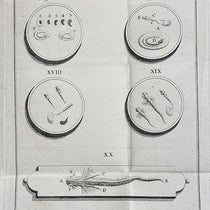

Baffin turned all his logs and maps over to Samuel Purchas for publishing in his series of voyages, but Purchas unaccountably did not publish any of them, just a summary, and the logs and maps were since lost. That was a disaster, because all knowledge of Baffin Bay slowly disappeared, and no one attempted to follow up on Baffin’s 1616 voyage for over two centuries. Fortunately, John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty in the 1810s, believed in the stories he had heard about Baffin, and he sent out the first modern search for a Northwest Passage in 1818, with John Ross in command of the Isabella and Alexander. The ships duplicated almost exactly the path of the Discovery in 1616, finding Lancaster, Jones, and Smith sounds just where Baffin said they would be. In fact, the map produced by the 1818 voyage could well serve as the lost map of Baffin of 1616 (first and third images). The Discovery had been prevented by ice from entering Lancaster Sound; the Isabella was blocked by incompetence, as Ross claimed the Sound was obstructed by a mountain range. Fortunately, a furious Ross sent William Parry back out in 1819, and Parry and his ships and crew sailed right through Lancaster Sound and half-way across the Arctic archipelago. It was a completion, two centuries later, of the voyage begun by Baffin.

After the 1616 Discovery voyage, Baffin turned his attentions to the East India Company, perhaps hoping to find the Northwest Passage from the Pacific side. He spent the rest of his life in the East Indies, and died of a gunshot wound during the siege of Ormuz in 1622.

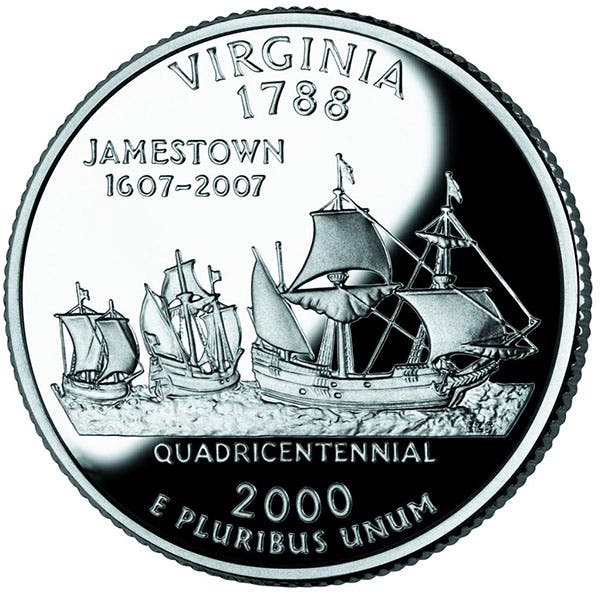

To me, one of the most remarkable aspects of Baffin’s last two arctic voyages is the ship he made them in. The Discovery was a tiny, tiny vessel. It was apparently quite maneuverable, and thus well suited to travel in ice-laden seas. But a collision with even a mid-sized marine mammal would have been a fatal flow. The original Discovery does not survive, but because of its role in founding the Jamestown colony, replicas were made in the 1980s of all three Jamestown ships for the Jamestown historic site, and we see above a photograph of the three (fourth image). The Susan Constant, on the right, was the largest of the trio, and it was not very big. The Discovery replica is the one in the middle. I cannot imagine being one of the 17 crew members as this vessel plied its way up Baffin Bay to a latitude of 77° 45’, a record that would not be equaled until 1852. What an amazing voyage of discovery that was, and no wonder Baffin is often called the greatest English navigator before Captain James Cook. Since we have room, we also show a photo of the Virginia state quarter, which depicts the three Jamestown ships, with the Discovery at the far left.

There is no known portrait of Baffin, although many biographical articles are illustrated with a portrait of a navigator in the Royal Museums Greenwich. There is no reason to think this is Baffin, and many reasons to believe that it portrays someone else.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Columbine, hand-colored woodcut, [Gart der Gesundheit], printed by Peter Schoeffer, Mainz, chap. 162, 1485 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3829b99e-a030-4a36-8bdd-27295454c30c/gart1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)