Scientist of the Day - William Edward Parry

William Edward Parry, an officer in the British Royal Navy, was born Dec. 19, 1790. Parry was part of the very first British Arctic expedition in search of a Northwest passage in 1818 (see our post on John Ross), and then he led four more follow-up expeditions between 1819 and 1827, each of them resulting in a narrative volume adorned with handsome lithographs. I wrote a post on Parry 8 years ago, when this blog was just underway, but for some reason, I wrote about the second voyage, probably because it had the first illustrations of the Inuit of the North in action, fishing for seals at ice-holes or building igloos. Today, we want to return to the first voyage, which was the most successful of all the Arctic voyages between 1818 and 1848.

Parry set off in 1819 with two ships, HMS Hecla and Griper, to follow up on the Ross expedition of 1818. The Hecla was a "bomb vessel," a rugged Navy ship, but the Griper was a brig and not very seaworthy. Parry had the same instructions as Ross had been given, to head up Baffin Bay and look for a passage west. Unlike Ross, Parry followed those instructions, sailed into Lancaster Sound at the top of Baffin Bay, and found that it went straight west, and was relatively free of ice, at least in the summer of 1819. They kept going, encountering other passages and islands that they named after High-Admiralty figures, such as Barrow Strait, Cornwallis Island, and Beechey Island. They made it across the 110° longitude line to an island they named Melville Island, where they would spend the winter, iced in at what they christened Winter Harbour.

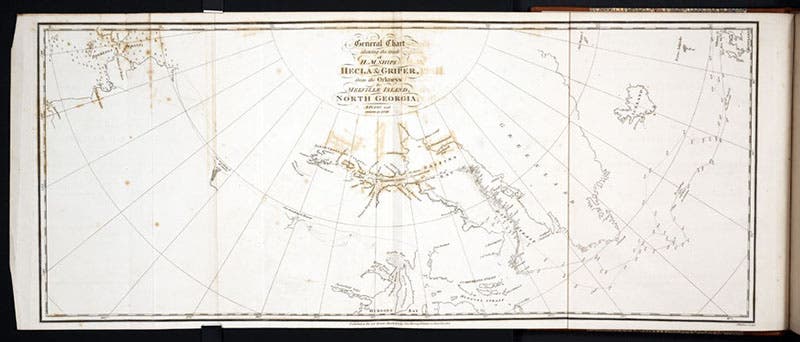

Map of the Arctic archipelago, virtually unexplored until Lt. Parry sailed through Lancaster Sound all the way to Melville Island (see detail, next image); before Parry, the center part of this map, like the rest, would have been completely blank; engraving in Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage, by William Edward Parry, 1821 (Linda Hall Library)

Detail of Parry’s map of the Arctic archipelago (third image), showing the path of HMS Hecla and Griper from Baffin Bay through Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait to Melville Island and their camp at Winter Harbour, detail of an engraving in Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage, by William Edward Parry, 1821 (Linda Hall Library)

If one looks at a map of the complete Arctic archipelago, such as the one provided in Parry's ensuing narrative (third image), you can see all the places and passages named in the center – we provide a detail so that you can see read most of the labels (fourth image). Everything west of Lancaster Sound was named and explored by Parry's crew. If you removed all the information gained by Parry's expedition from the map, it would be completely blank from Baffin Bay on west, for several thousand miles. More areas would be explored by later expeditions and the map filled out, but it was a slow process, as it was a fluke of the weather that allowed the Hecla and Griper to find ice-free passage so far west in 1819.

When the ice moved in as the autumn of 1819 progressed, the ships had to be prepared for wintering-over, which they had planned for, but this was still the first time any ships had actually done so. The top masts were removed, the decks covered over, using sails for tarps, and oil stoves were kept burning all the time. The crew hunkered down for the winter without sunlight, surviving on the recently invented tinned rations; when the boats thawed out the next summer, they headed home to report their success. John Barrow, the Second Secretary of the Admiralty, after whom Barrow Straits was named, surely felt better about this expedition than he had about the first one, led by Ross, that was such a failure.

As would become the norm for later voyages, Parry wrote a narrative of the expedition, called Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage (1821; sixth image). Because this was an official Admiralty publication, Parry could afford to commission and include many striking lithographs depicting the highlights of the voyage. We include two of those here, our first image showing HMS Hecla beset by an ice flow during their first month out, while still in Baffin Bay, while another (fifth image) depicts the winter encampment in Winter Harbour. Both lithographs were based on drawings by Frederick Beechey, one of Parry’s young lieutenants. We included Parry's narrative of his first voyage in our 2008 exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance, where we showed both of these images. I tried to choose new illustrations for this post, but how can you leave out either of these – they are both iconic images of Arctic exploration. However, we did here zoom in on the first image, so that you can better see the crew in longboats trying to pull the Hecla out of danger, and for the winter encampment, we pulled back a little, so that you can see the entire plate, just as it would appear if you were leafing through the book.

While Parry's ships were at Winter Harbour, one of the crew carved an inscription on a large boulder, proclaiming that the Hecla and Griper wintered there in 1819-20. Thirty-one ears later, a young lieutenant, Francis McClintock, part of a search for the lost Franklin expedition, found the rock while on a sledge journey and copied the inscription, which was then published in one of the "Arctic Blue Books" issued by the Admiralty in 1852. Since we have these Blue Books in our collections, I thought I would include the wood engraving of "Parry's rock," as it is still called (seventh image). Interestingly, the same Lt. McClintock would later discover the sad fate of the Franklin expedition, as you can see in our post on McClintock, or in our entry for Ice: A Victorian Romance.

On some future occasion, we will discuss and illustrate Parry’s third and fourth voyages – the latter especially interesting, since Parry tried to reach the North Pole by heading straight north from the British Isles, plowing unsuccessfully into the ice floes north of Spitsbergen.

The portrait of Parry we show here (second image) was painted just after he got back from Winter Harbour, when he was only 30 years old. We showed this same portrait in our first post on Parry, and I tried to find another for this occasion, but the only portraits that are not simply copies of this one were made in the 1850s, when Parry was a senior admiral, and they did not seem appropriate for his first voyage. So Samuel Drummond's fine oil portrait of 1820 makes a second appearance today. It can be seen in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.