Scientist of the Day - William Maclure

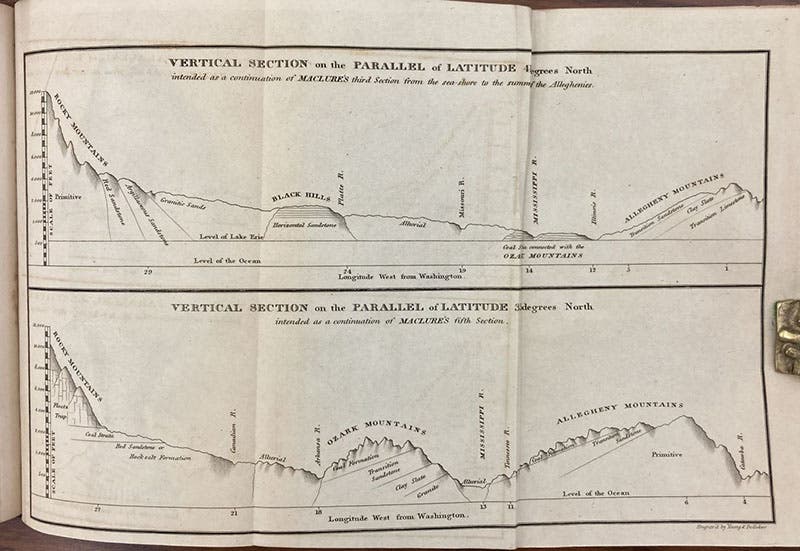

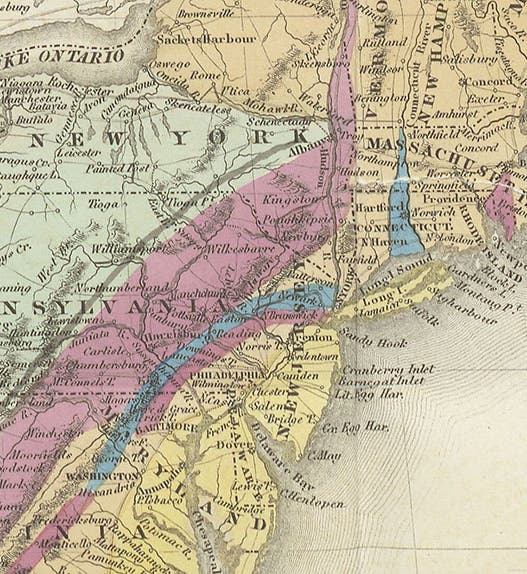

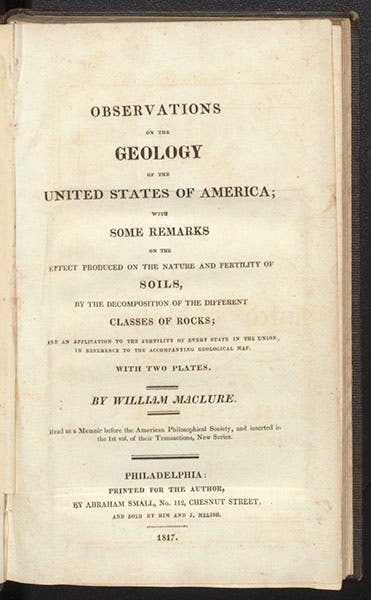

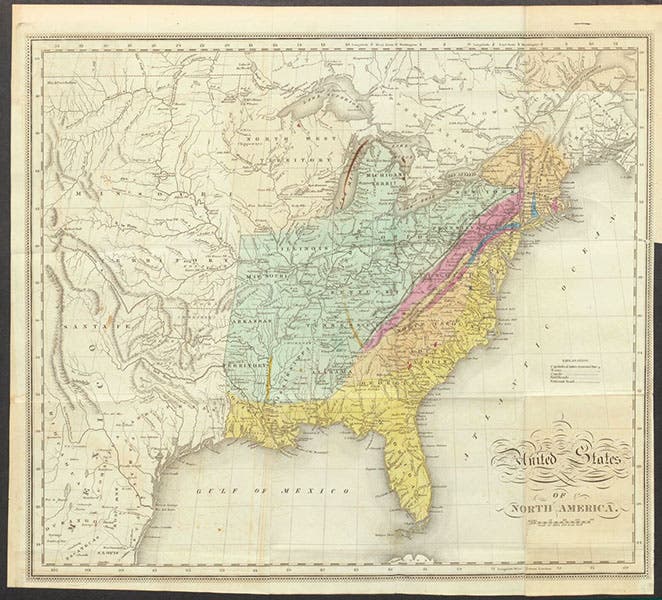

William Maclure, a Scottish geologist, collector, and philanthropist, who also worked in France, Spain, the United States, and Mexico, was born Oct. 27, 1763, in Ayr, Scotland. Maclure accrued quite a fortune as a merchant based in Scotland, and his business brought him several times to the United States. In 1796, he decided to stay, and he, over the next 15 years, made his mark as the country's first geologist, publishing a well-known geological map of the Eastern half of the country in 1809 and again, revised, in 1817. He became an enthusiastic member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (he was not quite a Founding member, but he joined several months after the Academy first convened in 1812). He gave generously when the Academy needed funds (which was often in the early years), and he professionalized the Academy by ensuring that it publish a journal, the first volume of which appeared in 1817. We have in our collections not only a complete run of the Journal of the Academy, but also two copies of Maclure’s Observations on the Geology of the United States of America (1817), both copies of which contain, as a folding frontispiece, a large hand-colored engraved map of the eastern half of the United States. We show a detail of the map, centered around Philadelphia, as our first image, and the entire map as our fourth image.

Portrait of William Maclure, oil on canvas, by Thomas Sully, 1825, Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University (courtesy of Robert M. Peck)

Maclure was very active in the affairs of the Academy and worked hard to ensure the success of the Journal. He encouraged Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, whom he met in Paris in 1816 and convinced to come to Philadelphia, to write and illustrate natural history articles for the Journal, and he provided the funds that made it possible to include occasional hand-colored engravings in the volumes (seventh image), a luxury usually denied to fledgling journals in the early 19th century. Maclure also led collecting expeditions, which helped add specimens to the Academy’s museum.

Maclure was also greatly interested in educational reform and was enamored of the ideas of the Swiss educator, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi; Maclure founded several Pestalozzian schools in the Philadelphia area. When the socialist Robert Owen established the utopian community of New Harmony in Indiana, Maclure jumped on board, and even convinced other members of the Academy, such as Thomas Say and Lesueur, to join him. They floated down the Ohio River to Indiana in 1825 on what has been called the "Boatload of Knowledge” (Thomas Say even meet his wife Lucy Sistaire on the boat journey). The experiment only lasted three years for Maclure, as he and Owen disagreed sharply on a number of ideological matters, and Maclure, who was now in poor health, then retired to Mexico in 1828.

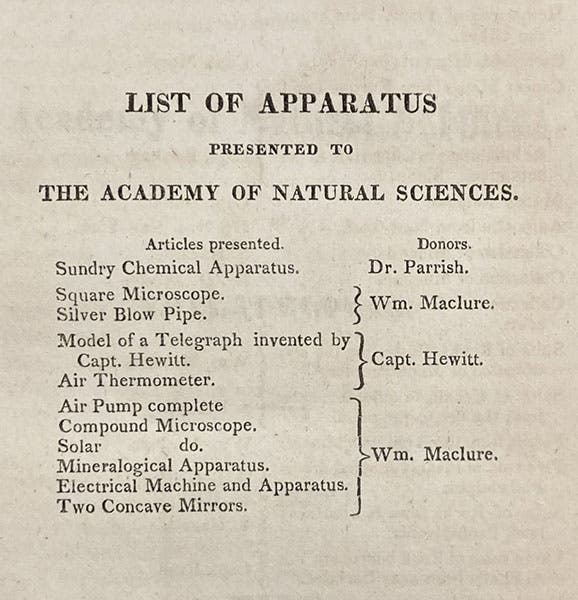

Maclure was elected President of the Academy in 1817, and he held that position until his death in 1840, which is quite amazing, considering that for the last 15 years of his presidency, he was nowhere near Philadelphia. My guess is that he was allowed to retain his absentee position because he was so generous with gifts of equipment, books, and funds to keep the Academy not only afloat, but thriving. And there was the possibility that the Academy might receive a substantial portion of Maclure’s estate, which was considerable.

To give you an idea of the extent of Maclure’s largesse, a catalog of the Academy library was made in 1836. It contained 6,890 volumes, of which number, 5,232 volumes had been donated by Maclure. Many of the pages of the Academy’s Journal acknowledge the receipt of books or lab equipment such as the page we show here (sixth image), and invariably, Maclure was the principal contributor.

Maclure died as he was attempting to return to New Harmony from Mexico in 1840, when he was 76 years old. He was buried in the town of San Ángel, and the Academy had a small monument placed on his grave, but it was plundered and destroyed early on, and I do not believe its location is known today. His will provided for the establishment of 160 workingmen’s libraries throughout the country (in 1838, he had provided the Workingmen’s Institute at New Harmony with a library of 15,000 volumes); none ot the 160 libraries survives today. The rest of his estate did go to the Academy, and they do greatly appreciate him as their principal benefactor right up to the resent day.

Portrait of William Maclure, oil on canvas, by Charles Willson Peale, 1818, The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University (courtesy of Robert M. Peck)

The Academy owns two portraits of Maclure, one painted by the patriarch of Philadelphia portrait artists, Charles Willson Peale (1818, ninth image), and the other by Thomas Sully (1825; first image), who painted the famous portrait of Andrew Jackson, whose green gaze can be found on every U.S. $20 bill.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Varieties of Actinia [sea anemones]”, hand-colored etching, illustrating an article by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, vol. 1, 1817 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1ea1ae0d-59c6-4b69-b311-41a54a2521af/maclure7.jpg?w=375&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)