Scientist of the Day - William Oughtred

William Oughtred, an English mathematician and Anglican priest, died June 30, 1660, at the age of 86. Oughtred wrote a number of mathematical works, two of which we have in our Library. But he also invented the slide rule, which will occupy our attention today. Until the 1970s, the slide rule was the centerpiece of the personal arsenal of every physicist or engineer. John Napier had invented logarithms in 1614, which were useful in calculations, since instead of multiplying two numbers together, you could add their logarithms, and addition is always easier than multiplication. An English mathematician, Edmund Gunter, made the first logarithmic scales, and realized that, if you wanted to multiply 2 times 4, you could set some calipers to the logarithm of 2 on the scale, then place one end of the calipers on 4, and the other end of the calipers would rest on the logarithm of 8. This was an easy mechanical way of adding the log of 2 to the log of 4, or multiplying two by four. What Oughtred did, perhaps by 1622, was to make two logarithmic scales, and slide them along each other. This got rid of the calipers but gave the same result. He did not come up with the clever idea of having a tongue-and-groove slide between the scales (a feature of most modern slide rules), but he may have made a circular slide rule, with one disc rotating on another larger one. If he did, it does not survive in any form.

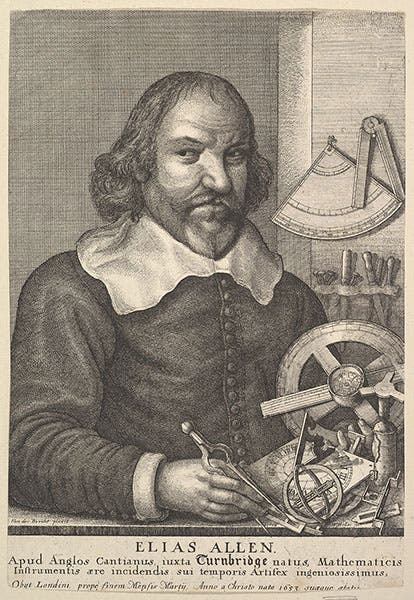

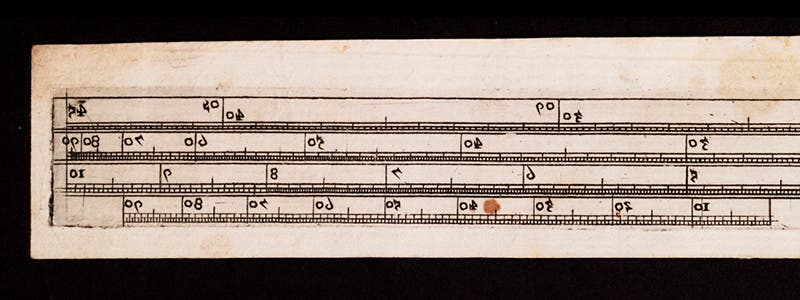

An actual slide rule was fabricated in 1638, by instrument maker Elias Allen, at the request of Oughtred. Allen’s portrait is our second image. The instrument does not survive, but a print does. An engraved instrument scale is no different than an engraved copper plate, in that, if you ink it and wipe the surface clean, you can press it onto a piece of paper and pull a print from it. A paper print from Allen’s instrument survives; it was part of the Macclesfield collection of papers and is now in Cambridge University Libraries. We include here photos of the entire scale, which you cannot read, and a detail of one end, with you can read (third and fourth images below). You will notice that the scale is backwards, as you would expect if you pull a print from something that reads forwards. Several years ago, Boris Jardine wrote a blog about the printed slide rule scale at Cambridge, revealing its existence. We drew our images of the scale from that blog. Jardine also observed that if you wonder why Oughtred didn’t build a slide rule and Allen did, all you have to do is look at the portraits of the two (both, incidentally, by Wenceslas Hollar). It should be no surprise that the man whose attribute was a book might not be interested in practical matters, while a man who identified with measuring instruments just might be.

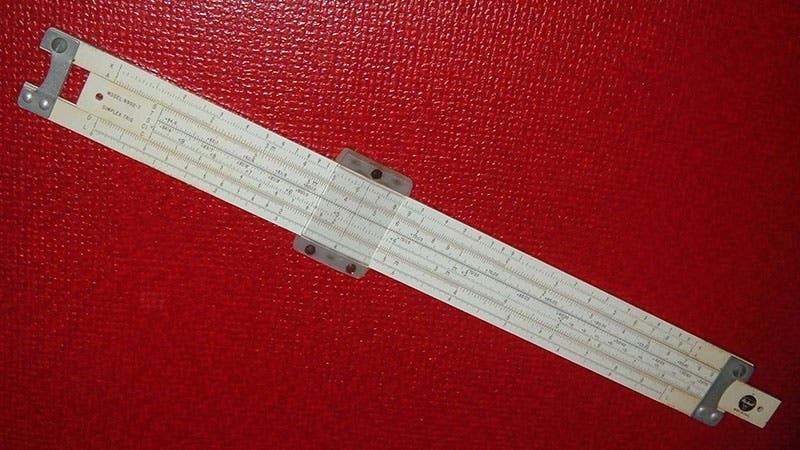

The slide rule was king of calculators for 300 years. In my day, picking out your college slide rule (for us science geeks) was as big a deal as selecting a smart phone is today. Fortunately, you didn't have to sign a two-year contract to use them, and they lasted forever. The better-built instruments were treasured and handed down from father to son like fine china. I still have my Dad’s Keufel & Esser slide rule from the 1940s, as well as my own. If you are younger than 45 and have never seen a slide rule, we include an unsophisticated example below (fifth image). The C and D scales were used for multiplying; the D and A for squares and square roots, and other scales were for trig functions. If you would like to practice, here is a link to a virtual slide rule, where the center rule actually slides and the cursor moves. Slide the center scale until the “1” on the C scale lines up with the “2” on the D scale, and you can read off the solution to “2 x 2” under “2” on the C scale, or “2 x 3” under “3”, etc. Slide the cursor over “5” on the A scale at top, and you can read off its square root (to three significant figures) below on the D scale: “2.23(60…)”. You can learn more at this self-guided online instruction manual.

As fun and satisfying as it is to use a slide rule, it should not surprise anyone that the first time an engineer got to use a Texas Instruments SR-50 calculator (1974), he put his slide rule in a drawer and never opened it again. We should not mourn the passing of the slide rule, but we do.

Whenever we celebrate a death date instead of a birthday, we like to include a photograph of a gravestone or churchyard. Oughtred’s final resting place is especially appropriate, since he served as rector of St Peter and St Paul’s Church in Albury, Surrey, for 50 years. It looks like a nice place to be interred.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)