Scientist of the Day - William Raynolds

William Franklin Raynolds, an American Army officer and topographical engineer, was born Mar. 17, 1820, in Canton, Ohio. In 1859, Raynolds set off in command of a small expedition to explore the entire Yellowstone River basin, an area of about 250,000 square miles! Several civilian fur traders and explorers had visited the upper Yellowstone basin and reported on the thermal springs and geysers there, but no "official” explorer had yet to see these marvels and confirm their existence. The natural candidate to lead such an expedition was Gouverneur Warren, who had been part of three expeditions in the area (1855-57), who knew all the mountain men, and who had just completed a fabulous map of the entire known western territory, which would be printed in 1861 (see our post on Warren). But for some reason hard to fathom, Warren had been removed from the frontier and sent to teach at West Point. So the expedition fell into the lap of Raynolds.

The expedition set out from Fort Pierre in South Dakota in 1859 and headed west. To improve their chances of success, Raynolds’ guide was Jim Bridger, one of the mountain men who had already seen the upper Yellowstone basin. The expedition went west and then south along the Big Horn Mountains, and was the first government expedition to enter into Jackson's Hole and the Grand Tetons. But they couldn't make it over the passes to the upper Yellowstone basin – there was too much snow. So Raynolds lost the chance to be the first Army officer to witness and map the grandeur of Yellowstone, and that honor would fall instead to the Langford-Washburn expedition of 1870 (see our posts on Nathaniel Langford and Henry Dana Washburn).

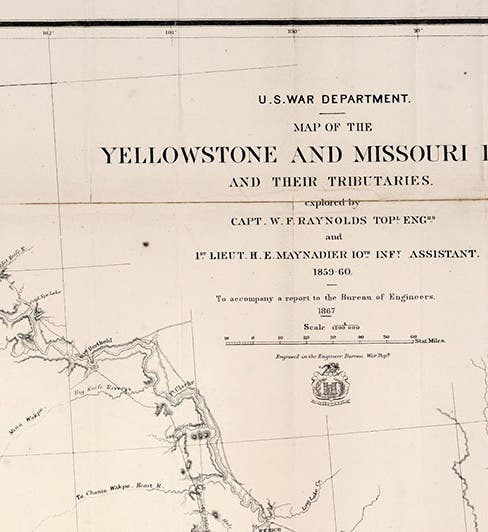

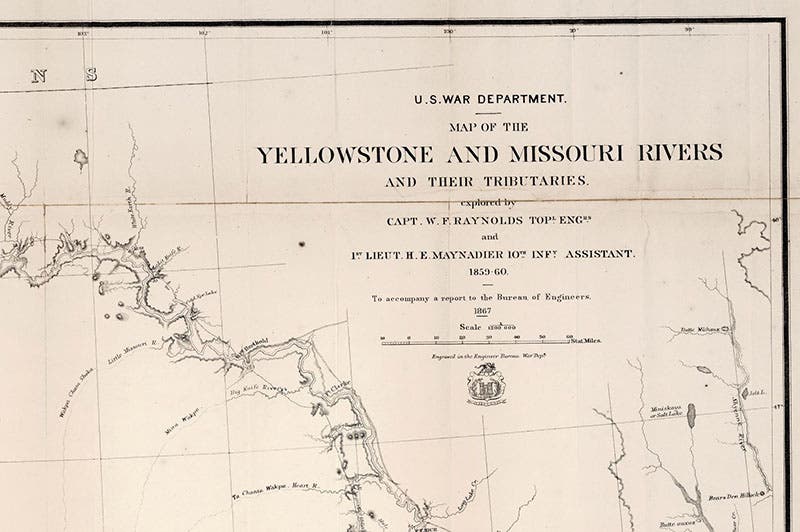

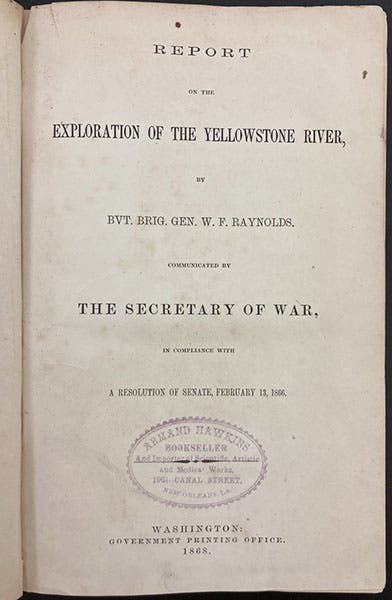

However, Raynolds did produce a map of the Dakotas-Wyoming-Montana area that was superior to any previous map of the region, including Warren’s, with some details of the upper Yellowstone (but not the geysers) being filled in by Bridger. The map was intended for Raynolds’ narrative of the expedition, publication of which, because of the war, was pushed off until 1868. We have a copy of Reynolds’ Report on the Exploration of the Yellowstone River (1868) in the History of Science Collection (second image), and it contains the map at the back, but the map has come apart at the folds, and the paper is so brittle that I did not even attempt to lay it out. Perhaps some conservation efforts may yet preserve it. You can see a 1868 Raynolds map, in much better condition, here as our third image, taken from the website of the David Rumsey Map Collection; on the website, the map is fully zoomable. We have drawn our details (first, fourth, and fifth images) from the Rumsey map as well.

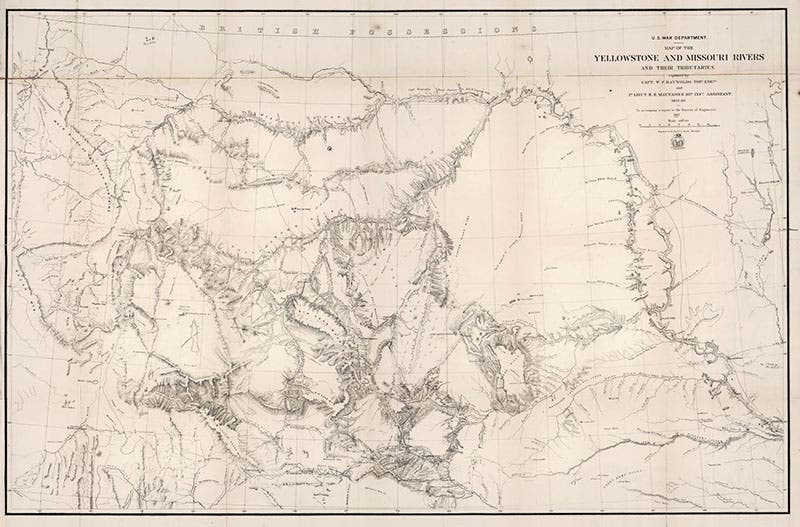

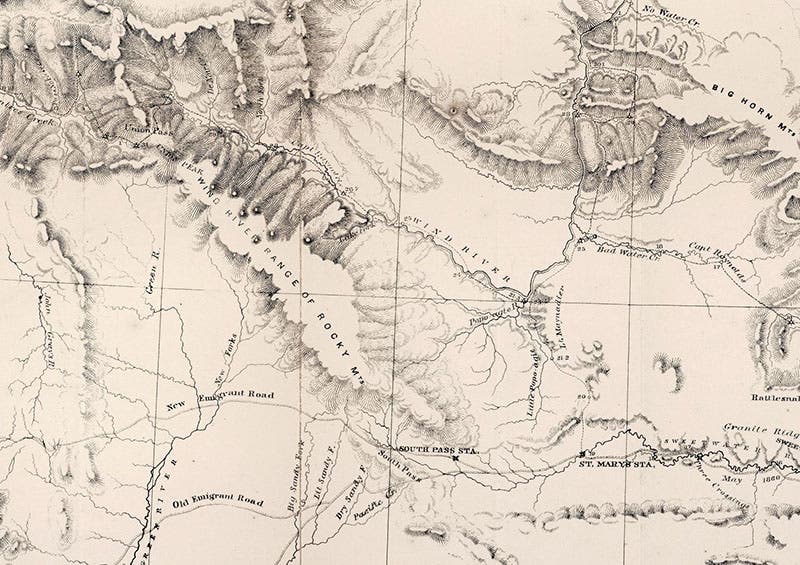

Note that the upper Yellowstone basin region of the map (fourth image) is devoid of details (except for Yellowstone Lake and the Falls), so none of the geysers or mudpots are indicated – Raynolds never saw them. The detail showing the Wind River Range (fifth image), which is southeast of Yellowstone, marks the location of South Pass, used by many of the wagon trails to the West, including the Oregon Trail and the California Trail. Frederick Lander had built a cut-off in 1859 that shortened the distance to Oregon by 8 days; it is labelled here the ”New Emigrant Road,” and is now called the Lander Road. We wrote a post on Lander just two weeks ago.

Detail of the Wind River Range and South Pass; the Oregon Trail is marked as the ‘Old Emigrant Road’, the Lander Cut-off as the ‘New Emigrant Road,’ “Map of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers and their Tributaries,” by William F. Raynolds and H.E. Maynadier, 1868, David Rumsey Map Collection`(davidrumsey.com)

The Raynolds expedition was the last of the many Western exploring expeditions sent out under the auspices of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. After the Civil war, most of the great surveys of the West, such as the surveys of Clarence King and Ferdinand Hayden, would be civilian affairs.

We might also devote a short paragraph to the guide on the Raynolds expedition, Jim Bridger, since he is also celebrating a birthday today, having been born on Mar. 17, 1804. Bridger was perhaps the most renowned of the mountain men (with a nod to Jedidiah Smith). He trapped through most of the west, became a partner in the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, a rival to the Astor conglomerate, and established a trading post at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, which led to a rerouting of the Oregon Trail. After losing his fort to the government during the war, Bridger returned to Kansas City in 1868 and set up a store, which he ran for years before passing away in 1881, at the age of 77. He is commemorated (along with two others) by a bronze statue, The Pioneers, in Westport Square in Kansas City, which today, St. Patrick’s Day, will be rather busy. Bridger is the figure on the right, under a hat. Some day he may get his own post, perhaps as Mountain Man of the Day.

It is a sheer calendrical coincidence that yesterday’s Scientist of the Day, John Navarre Macomb, and today’s, William Raynolds, were both members of the U.S. Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers; led the last two expeditions sponsored by the Corps into unexplored western territory in 1859, Macomb into Colorado and Raynolds into Montana and Wyoming; and produced historically significant maps of their respective areas of exploration. Such coincidences are all too rare, but welcome when they do occur, at least to me.

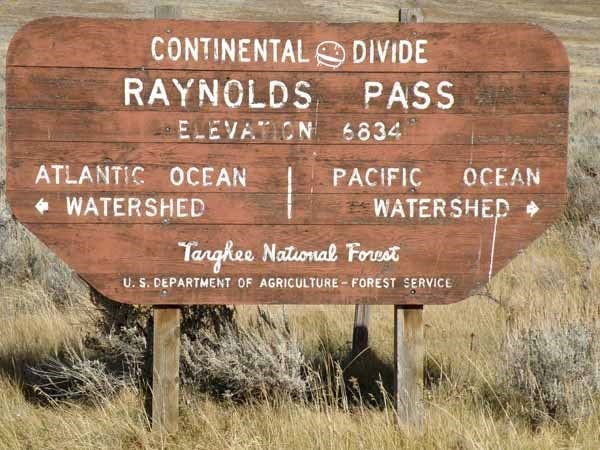

Raynolds had a whole separate career as a builder of lighthouses, which we might pursue on another occasion. There is only one portrait of Raynolds that I can find, and it is undocumented, so I will link to the Wikipedia version, but I will not reproduce it here. The lack of a portrait is very odd, for a man that was prominent in two fields. I hope to find a reliable portrait, perhaps in the U.S. Lighthouse Board records, and if I do, I will add it here. There is a pass named after Raynolds that crosses from from Montana into Idaho, and a sign has been posted there in his honor (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.