Scientist of the Day - Xavier Bichat

Marie François Xavier Bichat, a French pathologist and anatomist, was born Nov. 14, 1771. Bichat was the first to propose that tissue is a central element in human anatomy, and he considered organs as collections of often disparate tissues, rather than as entities in themselves. He thought that each of the many kinds of tissues is susceptible to its own dysfunctions and diseases. He was, in other words, the father of histology, the study of tissues. He set out his ideas in several books, including Anatomie générale (General Anatomy, 1801), and he was attempting (unsuccessfully) to get a position at the Faculty of Medicine in Paris, when he fractured his skull in a fall and died some weeks later. He was just 30 years old.

Bichat was already professionally established at the time of his death, and well respected by other important medical men in Paris, but he was hardly known outside the French medical world. Forty years later, his system of histology and pathological anatomy had taken both the French and English medical worlds by storm. When Marian Evans (better known as George Eliot) published her novel Middlemarch in 1871, a central character was the physician Tertius Lydgate, who was an ardent disciple of Bichat and wanted to institute Bichat's reforms in his clinic. The reader of Middlemarch learned a great deal about Bichat and tissues and disease (and the new cell theory, which post-dated Bichat).

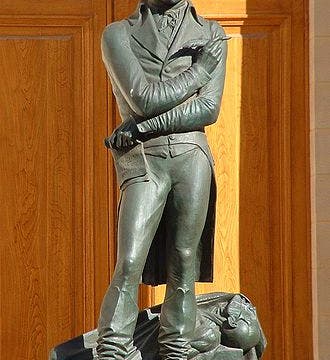

In 1845, there was a national meeting of French physicians in Paris. After his death, Bichat had been buried in a small cemetery, St. Catherine’s, which was being closed as unsanitary. So the conference organizers decided to disinter Bichat's body and move him to the Père Lachaise, the elaborate cemetery founded by Napoleon in 1804, two years after Bichat’s death, where the most distinguished luminaries were now customarily interred. An elaborate service in Bichat's honor was planned in the cathedral of Notre Dame, before which family and friends gathered in the decrepit St. Catherine’s cemetery for the disentombment. To everyone's surprise, the skeleton they dug out of Bichat's grave was lacking a head. After some consternation and confusion, a physician in the gathering came forth, bearing a skull that he claimed was that of Bichat. The physician had done the autopsy on Bichat 43 years earlier, but he offered no explanation as to why the skull had been detached or how he came by it. Nevertheless, Bichat tête was reunited with Bichat corps and the whole was conveyed to Notre Dame, where 4000 physicians paid their respects, and thence via a two-hour procession to Père Lachaise. The attendees also commissioned and paid for a statue of Bichat, executed in bronze by David d’Angers, which was installed in 1851 in the courtyard of the Medical Faculty of Paris (first image), the institution to which Bichat was unable to gain admission during his lifetime.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)