Scientist of the Day - Edward Wadsworth

Edward Alexander Wadsworth, an English painter, was born Oct. 29, 1889. Wadsworth was one of the founding members of an avant-garde movement known as Vorticism. Ten days ago, we discussed an Italian avant-garde artistic movement called Futurism (see our post on Umberto Boccioni). Futurism was caught up in the machine age and obsessed with speed and railroads, but when they tried to bring their movement to England and enlist English painters, some of them rebelled and decided to embrace the age of the machine in their own way. The Vorticist manifesto of 1914 (every new school seems to have begun with a manifesto) was written by Wyndham Lewis, and one of the first to sign on was Wadsworth. I am not an art historian, and it is hard for me to figure out exactly what unified the Vorticists, except that they were against impressionism and realism, admired Cubism but thought it too passive, used the vortex as a symbol for a concentration of energy, and liked representing things with lines.

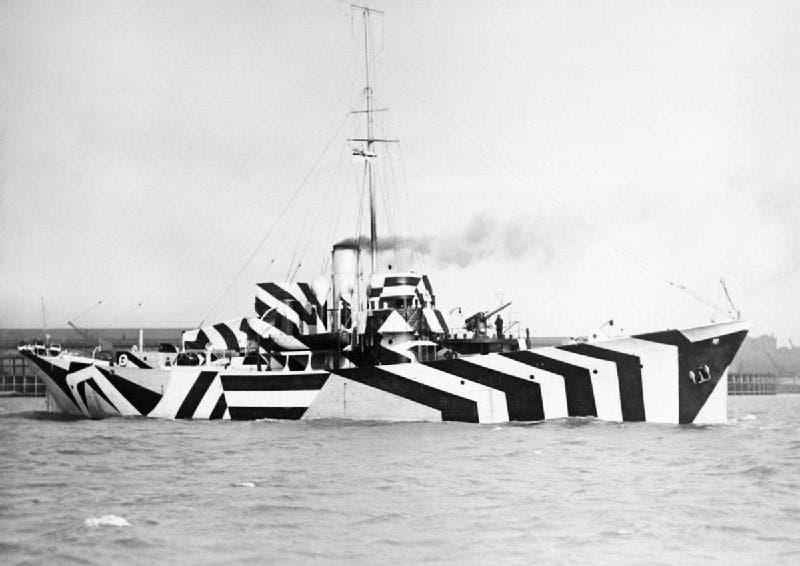

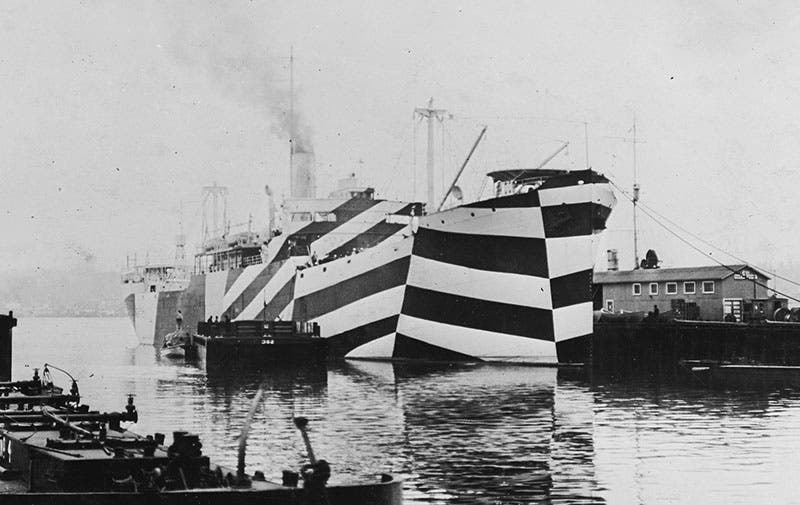

The Vorticists didn't have much of a chance to sort out their movement before England was launched into the First World War. Wadsworth enlisted, and apparently his love of lines got him the job of decorating warships with something called dazzle camouflage. This had first been proposed by another artist, Norman Wilkinson (not a Vorticist), who suggested that since you really can’t hide a battleship on the high seas, you could paint it in such a way that enemy observers would have a hard time figuring out what exactly they were seeing, which way it was going, and how fast it was travelling. This was best achieved, said Wilkinson, by painting ships with bold zig-zag lines at odd angles. He sold the idea to the Admiralty, who then put Wadsworth in charge of painting some 4000 ships. We show two of these here, both from World War 1. The photo below shows that the dazzle-ship movement spread to include the U.S. Navy.

The interesting thing about the dazzle ship project was that, since it was conceived by one artist and supervised by another, there was almost no scientific method involved. No tests were done beforehand, so the only reason for thinking that dazzle camouflage would work is because several people saw no reason why it shouldn't work. When the statistics came in after the war was over, it turned out that dazzle camouflage made very little difference. It seems slightly more dazzle ships were attacked than plain gray ships, but slightly fewer of them were sunk, so you could make the case either way, but either way, the case was weak. Since every ship had a different dazzle pattern, it was impossible to know what pattern, if any, was most effective. All we can say for sure is that it made life more interesting for U-boat captains looking at British naval vessels through their periscopes.

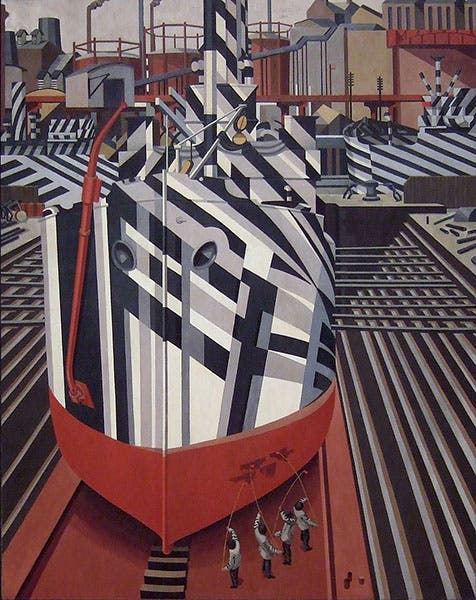

The reason why we use Wadsworth as a vehicle for discussing dazzle ships, rather that Wilkinson, is that Wadsworth was a better artist. And he used his Royal Navy experience to give us probably the most popular Vorticist painting of all, called Dazzle-ships in Drydock at Liverpool (1919, National Art Gallery of Canada) (fourth image, above). If every avant-garde art movement needs to have one painting to justify its inclusion in art-survey textbooks, one could do worse than choose Wadsworth's for Vorticism.

Wadsworth created many other paintings in the next thirty years (he died in 1949). I show my second-favorite Wadsworth painting, Seaport, painted in 1923, and now in the Tate. I am not sure that it says anything Vorticist – energy would seem to be distinctly lacking here – but I like it. Seaport reminds me of Penobscot Bay in Maine.

Our opening painting requires a little explanation. William Roberts was a one-time Vorticist who became involved in the 1950s in a controversy with the director of the Tate Gallery, whom Roberts accused of venerating Lewis in a retrospective and putting everyone else under the rubric “other Vorticists.” In 1962, perhaps in an attempt to atone for his vituperations of the 50s, he affably painted The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel: Spring, 1915, capturing a gathering of the group. Wyndham Lewis is the larger-than-life figure at the center, Ezra Pound is seated at left front, and our subject, Edward Wadsworth, is the balding fellow at right front, discussing the torte-of-the-day with the waiter. The Blast is the journal, founded and edited by Lewis, in which the Vorticist manifesto was first printed in 1915. The painting, appropriately enough, hangs at the Tate.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)