Scientist of the Day - Edwin Abbott Abbott

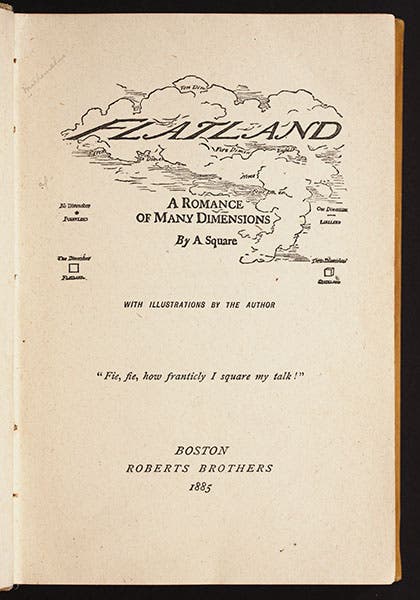

Edwin Abbott Abbott, a British headmaster, was born Dec. 20, 1838. Abbott is best known for a book that he published in 1884, titled Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. The book is at once a romance, a satire, and an allegory, as it tells the tale of a square (literally, “A Square”) who inhabits a two-dimensional world, and is one day introduced to the third dimension and to creatures such as cubes. Naturally, as he attempts to enlighten his fellow-Flatlanders about this new dimension in their lives, A Square is branded a heretic and thrown into prison, where, à la Boethius, he consoles himself by writing this book.

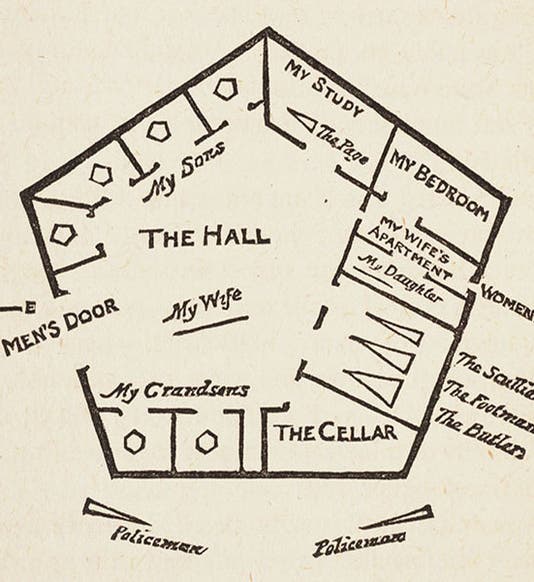

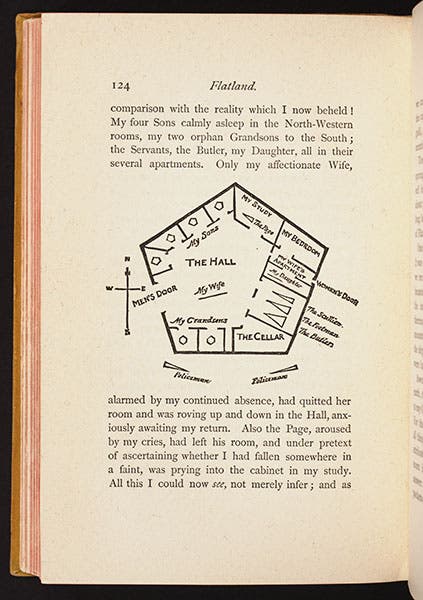

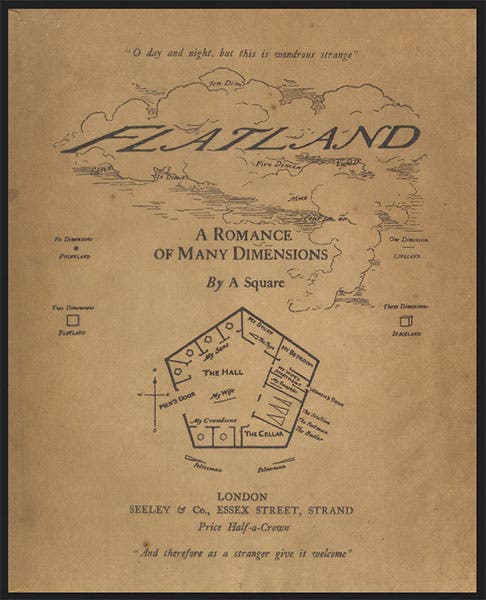

Most of the appeal of Flatland derives not from its warnings about the dangers of being close-minded, but from the delightful descriptions and drawings of daily life in Flatland. Abbott provides a diagram of A Square’s house (as seen from the third dimension, by the way; first image). Note that his servants are mere triangles, his sons (in their bedrooms at upper left) are pentagons, and his grandsons (at bottom) are hexagons. So the number of sides you have is an indicator of social status, and each new generation gains a side, suggesting some kind of upward mobility, so that everyone can have some future hope of “improving his angle”. But not the women, who are nearly one-dimensional, like needles, and who are so dangerous to men (because you cannot see them coming until they have run right through you) that they have their own separate house entrance at the right. The conjugal bed is next to Mrs Square’s entrance and apartment, so that would seem to be her primary function, but how she conceives and gives birth to polygonal offspring is a mystery upon which the book sheds no light.

Speaking of light, no one in Flatland knows where the light comes from that illuminates the insides of their houses. A Square knows – it comes from “above” – but since no one can imagine what direction that is, they agree that Mr. Square should continue to be mocked and locked up.

We have the first American edition of Flatland (1885) in our History of Science Collection, and the first four images above are drawn from our copy (the first image is just a detail of the fourth).

The first London edition has a paper cover with the house diagram repeated upon it; we show you the copy at Brown University Libraries (fifth image). Flatland has been continuously in print since it was first published, and you can find half-a-dozen paperback or Kindle editions on Amazon, if you are inclined to expand your horizons, or perhaps restrict them. It will take up no room on your bookshelf.

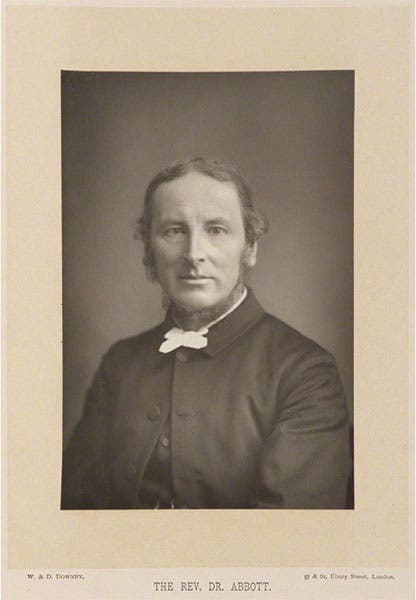

Our final image is a photo portrait of Abbott, taken in 1891, seven years after Flatland was published. It is properly two-dimensional. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.