Scientist of the Day - Francis Trenholm Crowe

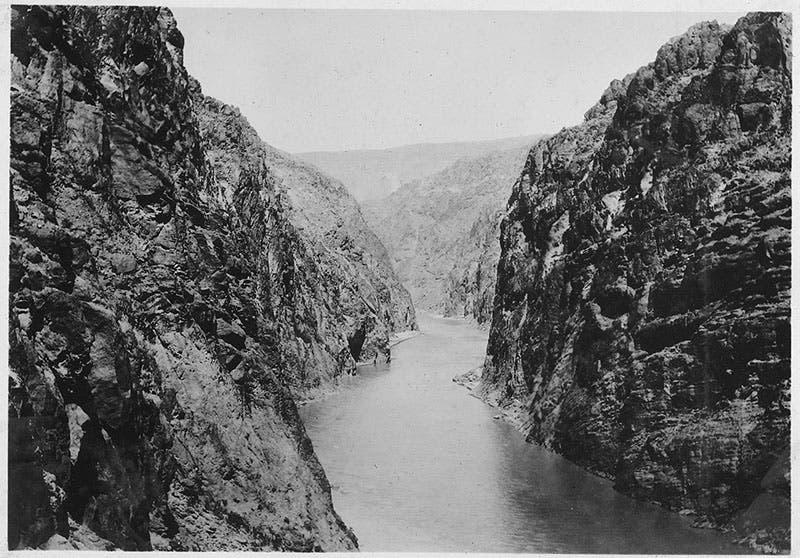

Francis Trenholm Crowe, an American civil engineer, was born Oct. 12, 1882. Fresh out of the University of Maine with his degree, Frank, as he was always called, joined what would become the U. S. Bureau of Reclamation, building dams. When the Bureau reorganized and decided to contract out its dam building, Crowe quit in 1924 and became a private contractor, and was quite successful. His big opportunity came when Congress, in 1928, authorized the building of a dam on the Colorado River at Black Canyon, on the border between Arizona and Nevada. This would be a huge dam, the largest ever, and since the project was too big for one construction firm, six of them banded together, calling their partnership Six Companies, and they hired Crowe as chief engineer. He submitted the companies’ winning bid in the spring of 1931.

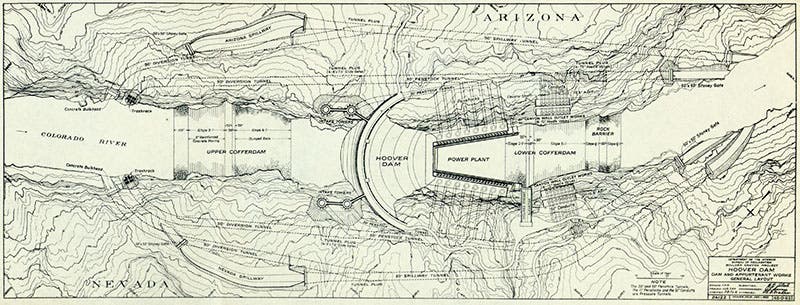

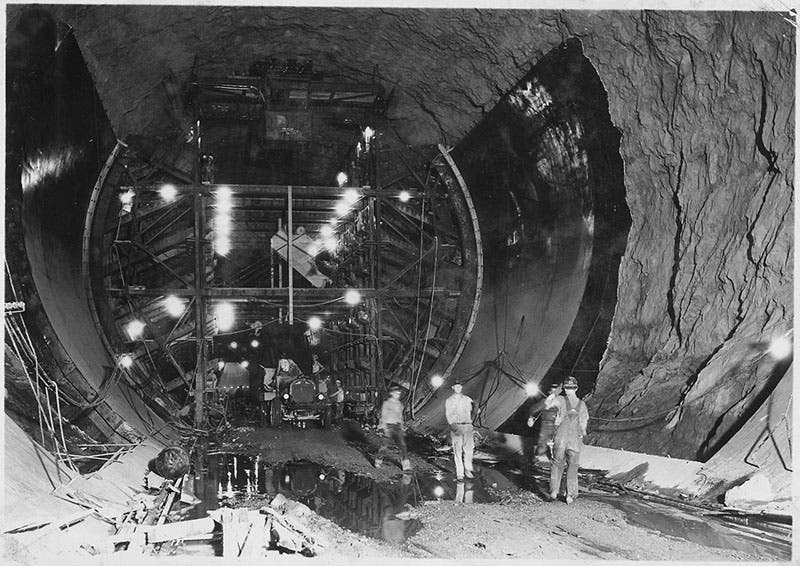

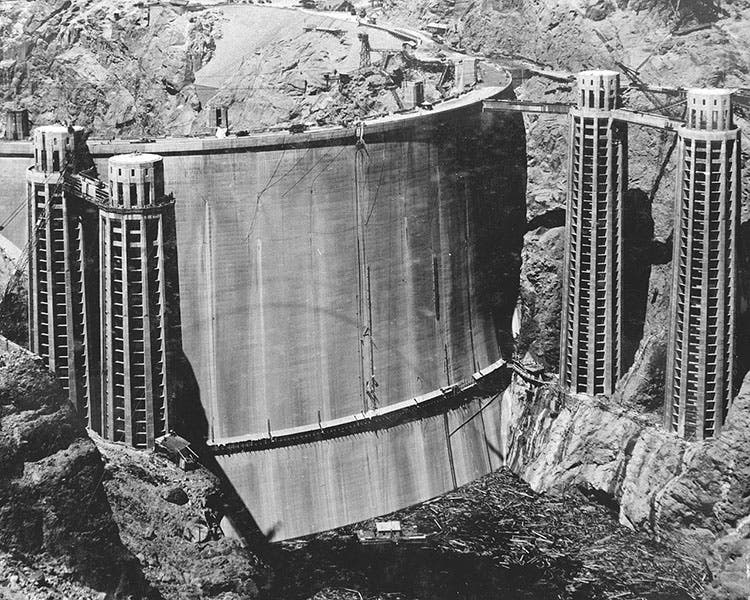

The project involved building a concrete dam over 700 feet tall, bowed upstream in the canyon to hold back the Colorado River. But before they could even start on the dam, they had to dig 4 diversion tunnels through the cliffs on either side to accommodate the river's flow, so that a cofferdam could be built and dam construction could begin. It took 19 months to build the tunnels, each of which was 56 feet across, or 50 feet once the concrete liner had been poured (fifth image). Crowe was credited with devising the "Jumbo" drilling rig, three vertical rows of 10 drillers each, stacked on a ten-ton truck, which greatly facilitated placing the dynamite for blasting (fourth image). Crowe started with 1400 workers for the tunnels; the work force would expand to over 5000, once the dam itself was under construction. Another innovative feature of the project was Boulder City, a model community built from scratch to house and feed the work force; it was ready for occupants by 1932.

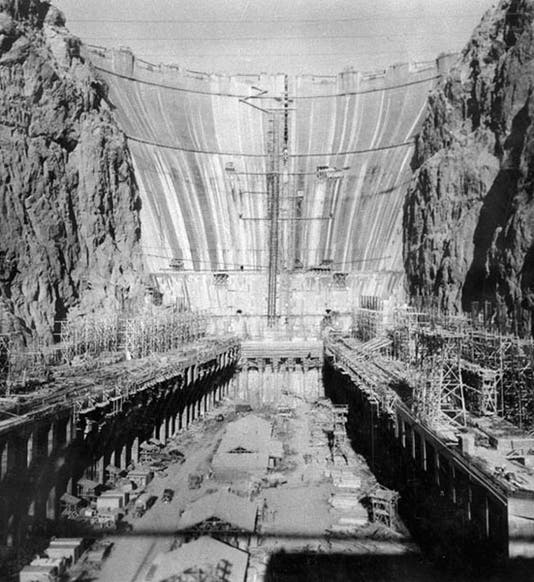

The design engineers decided to pour the dam in individual blocks about 50 feet square and 5 feet deep, which would be interlocked with grout. If it were poured as a single unit, the dam would have taken over a century to cool and harden. The logistics of that process must have been incredibly demanding on Crowe, especially when you see a photo of the block-pouring underway (sixth image). Crowe devised a delivery system for the concrete using overhead cables that greatly speeded things up. They could deliver a 20-ton bucket of concrete to any of the block forms, and do so once every 80 seconds. Still, it took from June 1933 to Feb. 1935 to convey tens of thousands of buckets to the hundreds of interlocked forms.

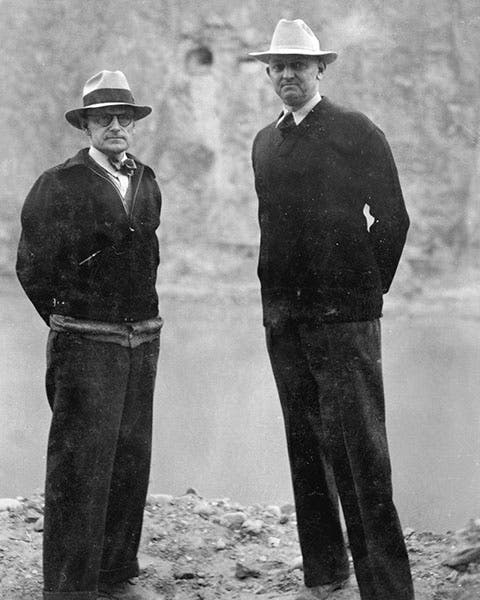

Crowe was very much a hands-on, feet-in-the-mud supervisor. Standing almost six and a half feet tall, he was a commanding presence at the dam site (seventh image, above). He seems to have been regarded by the crew as fair but demanding and impatient. “Hurry-up Crow” was his moniker among the workers.

The dam was dedicated on Sep. 30, 1935, by President Roosevelt. When construction began in 1930, it was announced by the Secretary of the Interior that the dam would be called Hoover Dam. That was not popular with many, as Hoover was blamed for the Great Depression that was well underway, and when Roosevelt was elected in 1932, his Secretary of the Interior immediately announced that the dam would be called Boulder Dam, and as such it was dedicated by Roosevelt. Not until 1947 would the name Hoover Dam be reinstalled.

The building of Hoover Dam was the largest engineering project in American history to date. It had an enormous impact on life in the American Southwest, not only taming the Colorado and making it possible for the land along the lower river to be farmed, but also providing 2 billion watts of electricity to allow for the expansion of cities, especially Los Angeles. Crowe is generally given much of the credit for the successful building of the dam, and for doing so two years ahead of schedule. However, many others were important for the design of the dam. For its appearance, much of the credit goes to the architect Gordon B. Kaufmann, who turned the dam into a shining representative of Futurism, and to the sculptor hired by Kaufmann, Oskar J.W. Hansen, who was responsible for the Art Deco sculptures that make the downstream side of the dam so memorable. Some future day, we will celebrate each of these men and take a closer look at Hoover Dam as a work of art.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.