Scientist of the Day - George Back

George Back, an officer in the British Royal Navy, was born Nov 6, 1777. Back made five sea voyages or land expeditions into the Arctic in the golden age of British Arctic exploration that began in 1818. He was part of the very first voyage to Greenland's east coast, led by John Franklin, in 1818, and he then accompanied Franklin on two overland expeditions north through Canada to the Arctic sea.

On the first of these, 1819-22, the unofficial artist was George Hood, but after Hood was murdered by a voyageur, Back assumed the role of expedition artist, and here he found his true calling. It would turn out that he was a much better artist than he was a naval commander. One of the sketches he did for Franklin, depicting a winter bivouac under the pines (third image), is so attractive that the Library used the image for its annual Holiday card some years ago

In 1833, when John Ross's voyage to Boothia Bay in the Arctic archipelago had not been heard from for several years, Back led an expedition up the Great Fish River in search of Ross's ship and crew. When he learned midway that Ross was safe, Back instead explored the Arctic coastline, returned home without mishap, and published an account of his adventures in 1836: Narrative of the Arctic Land Expedition to the Mouth of the Great Fish River. Back did all the illustrations for the Narrative, but they are fairly bland, as nothing much happened. We include one of his engravings here, showing what it was like to camp in the far north in the darkness of winter (fourth image).

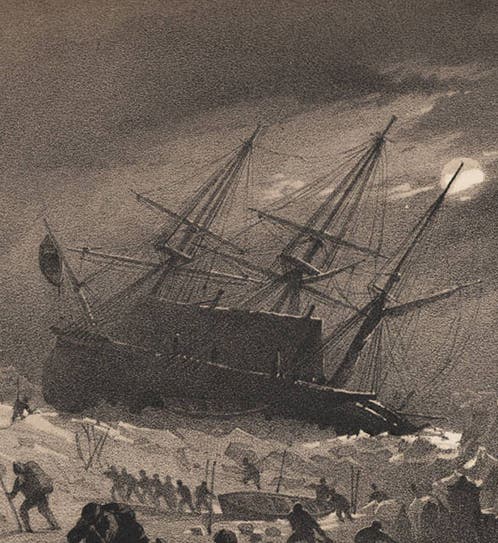

In 1836, Back finally received command of his own ship, HMS Terror, with orders to attempt to find a Northwest Passage through Repulse Bay. Things did not go well. The Terror was immediately beset in the ice, battered by ice floes, and after two years of going nowhere, the ship finally drifted out and barely made its way to Ireland before falling apart on the shore. Back would not get another command. But his book was a resounding success, since unlike his previous narratives, which depicted caribou and campsites, this one depicted many dramatic scenes of a ship being slowly crushed in the ice. The most dramatic shows the ship being unloaded by moonlight, as Back feared it was on its way to the bottom (first image).

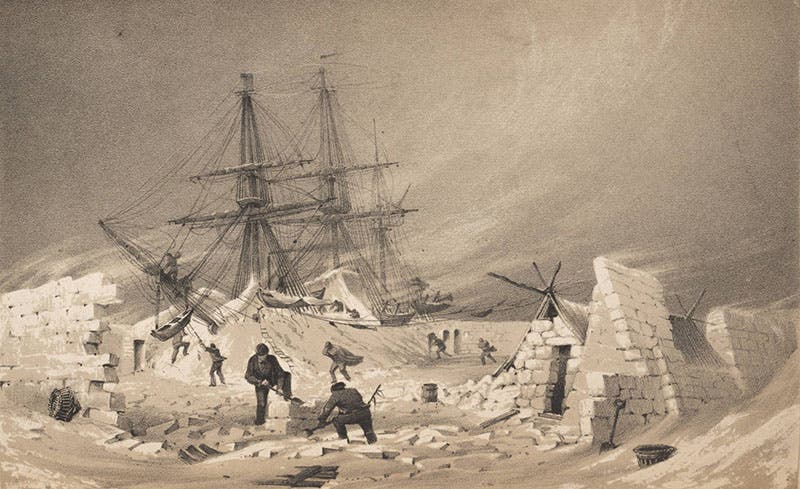

But other engravings are almost as alluring. One shows the men building winter quarters as the ship has been covered over with sails to protect against the winter cold (fifth image). Another shows the crew trying to dig a channel in the ice to free the Terror (sixth image). All of these engravings were based on drawings by Back.

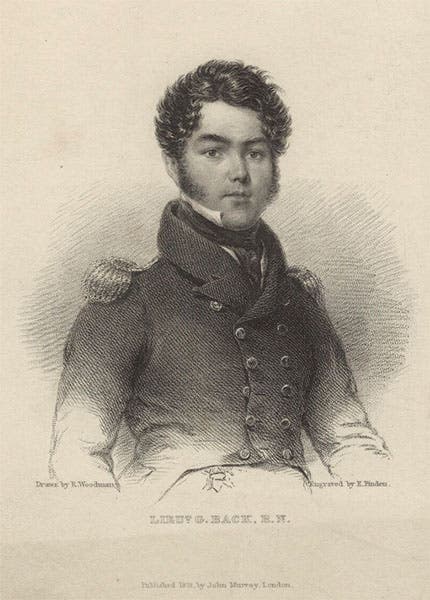

Stephen Pearce, a noted portrait artist, produced a group portrait in 1851 that showed all of the notable Arctic explorers; we have showed the portrait several times in these posts (for example, in our post on Pearce, where the group portrait is the first image. George Back is the leftmost figure of the ten, talking to Edward Parry. For all the figures in the group portrait, Pearce first painted individual portraits and then combined these on his canvas to produce his fake “group.” All of those individual portraits survive except that of Back. So we use here a stipple portrait (second image) that shows Back ten years before his voyage in HMS Terror.

Ten years ago, in our exhibition Ice: A Victorian Romance, we exhibited all three of the books discussed here. If you would like to see some additional illustrations (and a few that are the same), you can view the Franklin narrative of 1824 here, Back’s 1836 narrative ot the journey up the Great Fish River here, and the 1838 account of the Terror debacle here. And yes, Back’s Terror was the same ship that, after being completely rebuilt, accompanied HMS Erebus on a voyage to the southern polar sea in 1839-43, and then sailed along with Erebus back into the Arctic with John Franklin at the helm in 1845, only to disappear along with the entire Franklin expedition, not to be found until the 21st century.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.