Scientist of the Day - Henry Billingsley

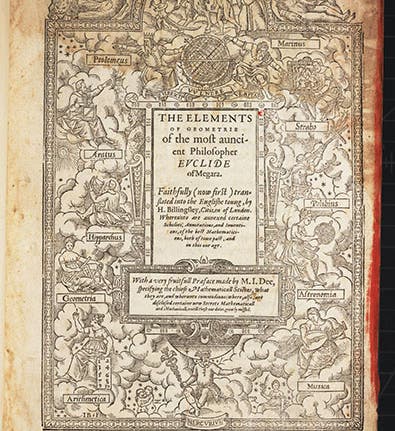

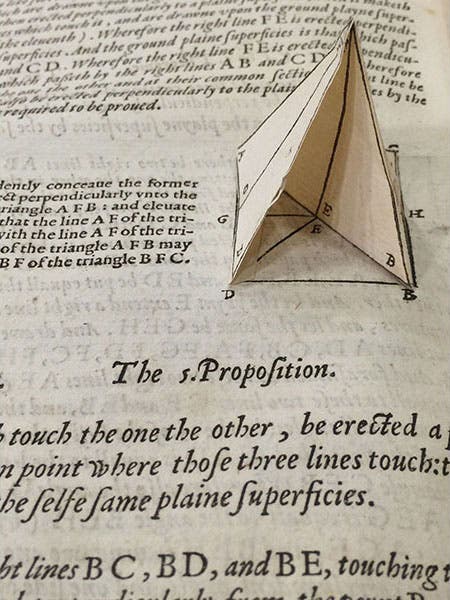

Henry Billingsley a merchant, amateur linguist, and Lord Mayor of London, died Nov. 22, 1606; we do not know the date or even the year of his birth. In 1570, long before he became mayor of London, Billingsley published the first English translation of Euclid, which he called Elements of Geometrie. The book contained a mathematical preface by the renowned John Dee, was published by the eminent London printer John Day, and is famous mostly because of the pop-up geometrical figures that are spread throughout Book 11, on solid geometry. Dee has received quite a bit of attention for his preface (which is not about Euclid but about the proper education of a natural philosopher), and Day has received credit as well for the printing (and the pop-ups) – indeed, both Dee and Day have been featured here as Scientists of the Say. But Billingsley has generally not received his proper share of the credit. Since mayors of London have seldom been scholars, it has usually been assumed either that Dee did the translation, or that Billingsley had considerable help from a real scholar.

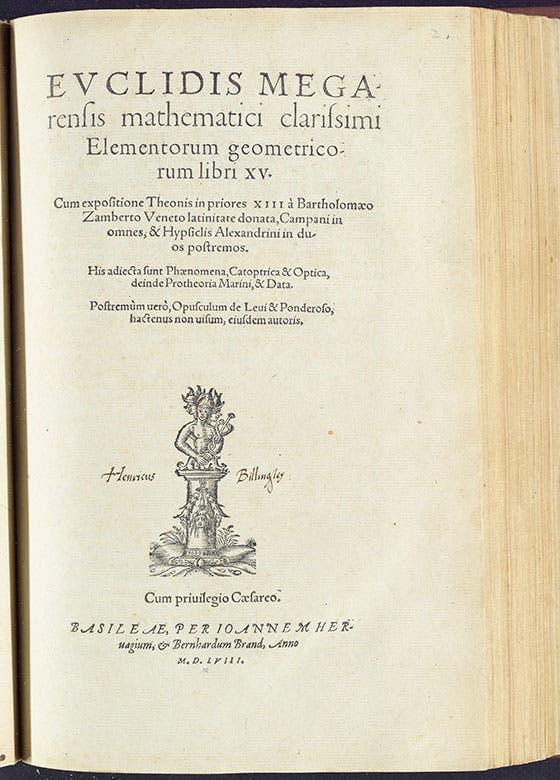

However, we now know – and should have known since 1879 – that not only did Billingsley make the translation himself, he did it from the original Greek, rather than from one of the Latin translations from Arabic that were available. We know this because the actual copy of the Greek edition that Billingsley used, printed in Basel in 1533, survives in the Princeton University Library. Bound with it is a 1558 Latin translation of Euclid’s Elements that has Billingsley’s beautiful signature right on the title page (fourth image). And the Greek edition of 1533 has copious annotations and corrections in Greek in the same neat hand that is clearly Billingsley’s. There seems to be no doubt that Billingsley read Greek well, made his own translation, and then compared it with the translation of 1558, in order to produce the best text possible. All the spade work for this conclusion was done in the 19th century by George Bruce Halsted, a tutor at Princeton, who discovered Billingsley's copy of the Greek Euclid in the Princeton Library and published a short note about it in the American Journal of Mathematics in 1879. We have added little here to what Halsted revealed in his brief article 140 years ago.

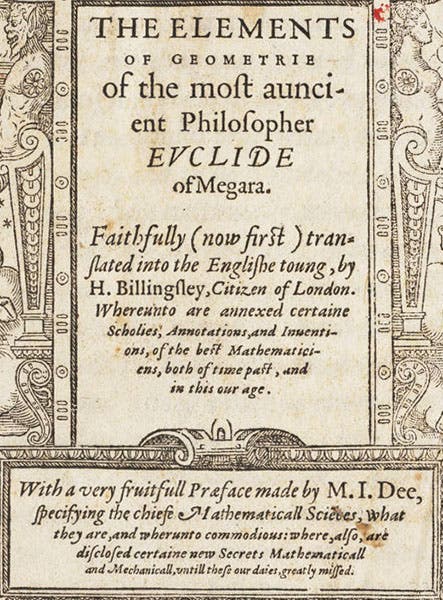

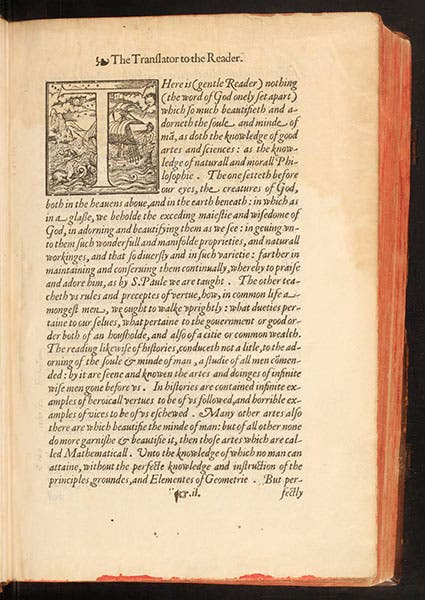

We exhibit here the title page (and a detail of that title page showing Billingsley’s name) of our copy of the 1570 Euclid; the first page of the translator’s (Billingsley’s) preface to the reader; and the title page of the 1558 Euclid at Princeton that has Billingsley’s signature.

And even though Billingsley probably had nothing to do with the pop-up paper polygons, we show a photo of one of ours, since it is this for which Billingsley’s Euclid is best known (fifth image). Many copies of this work are missing one of more of the 60 folding figures; our copy has every one of them intact. We also have a fine copy of the 1533 Greek Euclid, but it can not compare in interest with the Princeton copy, with Billingsley’s own annotations.

There is no portrait of Billingsley here because there is no portrait of Billingsley anywhere, which is a shame. He deserves to be recognized. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.