Scientist of the Day - John Evans

John Evans, an English businessman, antiquary, and seminal archaeologist, was born Nov. 17, 1823. Evans' uncle had established several paper-making plants; Evans went to work there, and eventually became a partner and managed business affairs until he retired. But he seemingly had plenty of time free to pursue his real love, which was finding and collecting ancient coins and stone tools. In the late 1850s, he became acquainted with an older geologist with similar interests, Joseph Prestwich. In April of 1859, the two met at the railway station in Abbeville, France, invited there to see the collection of Jacques Boucher de Perthes, who had assembled in his home an impressive collection of stone tools. Boucher de Perthes had found them in the gravels of the Somme Valley in northern France, and he believed that they were made by prehistoric humans. He had published the first volume of a book on the subject 22 years earlier, but found few adherents, as belief in human antiquity was almost nonexistent in the 1830s. By 1859, however, some investigators, including Evans and Prestwich, were now willing to look at the evidence. Unfortunately, Boucher de Perthes had only part of the needed evidence – he had the stone tools, but no proof that they were contemporaneous with the bones of extinct animals that were also found in the diluvial gravels.

On Apr. 27, while at Abbeville, Prestwich and Evans received a telegram stating that a stone hand-axe had been found in situ at the site of St. Acheul in nearby Amiens, in a river terrace, a dozen or so feet below ground level. Prestwich and Evans hustled over that same day, corralled a photographer, and had a picture taken of the tool jutting out of the bank. Apparently they found more than one hand-axe, for there is a tool in the Natural History Museum with Prestwich’s paper label that purports to be the one found that day, and another in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, with Evans’ paper label attached, making the same claim. Since this is a post on Evans, we show his Acheulean hand-axe here (first image).

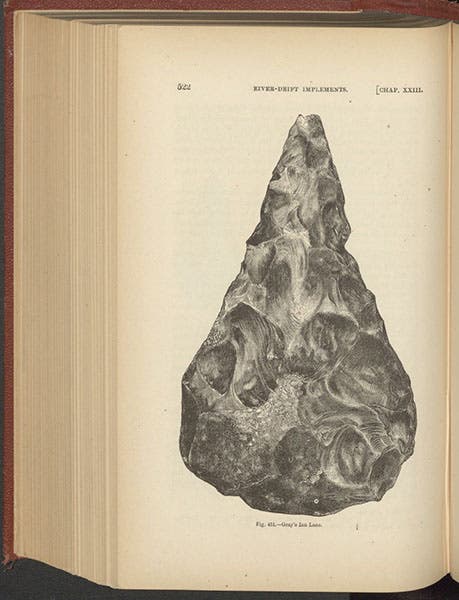

Flint hand-axe, found in Gray’s Inn Lane by John Conyers, late 17th century, wood-engraving, in John Evans, The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain, 1872 (author’s copy)

Title page, John Evans, The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain, 1872 (author’s copy)

Both men returned to London and immediately gave papers proclaiming that the debate was over – humans had lived on this planet long before recorded history and had made stone tools which they used to hunt animals now extinct. Prestwich gave his paper before the Royal Society of London and we have it in our collections, in the Philosophical Transactions of that society. Evans presented his paper to the Society of Antiquaries of London, and it was published in the society journal, Archaeologia, whose issues are represented only piecemeal in our Library, and we lack the issues of the 1850s and 1860s that contain Evans’ papers.

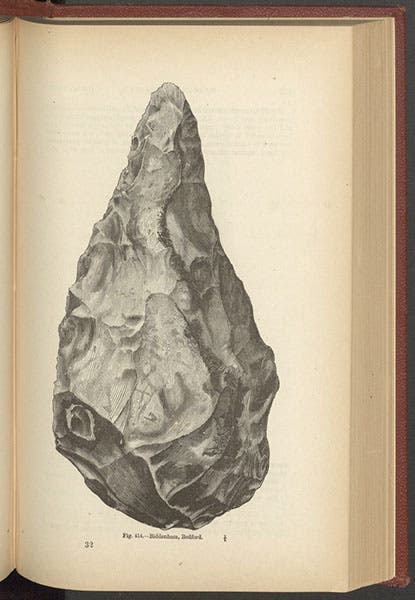

Flint hand-axe from Biddenham, Bedford, wood-engraving, in John Evans, The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain, 1872 (author’s copy)

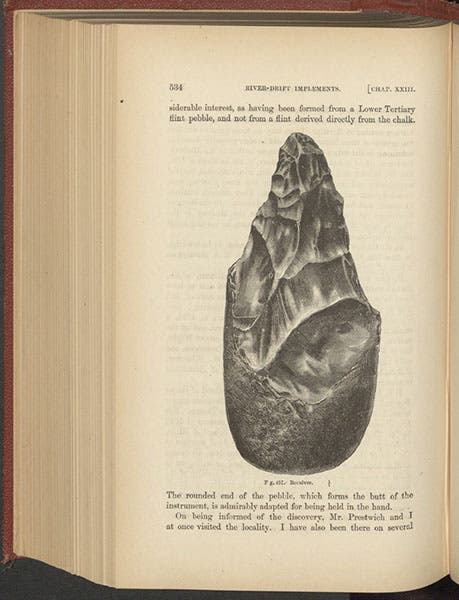

Flint hand-axe from Reculver, Kent, found by Thomas Leech, 1860, wood-engraving, in John Evans, The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain, 1872 (author’s copy)

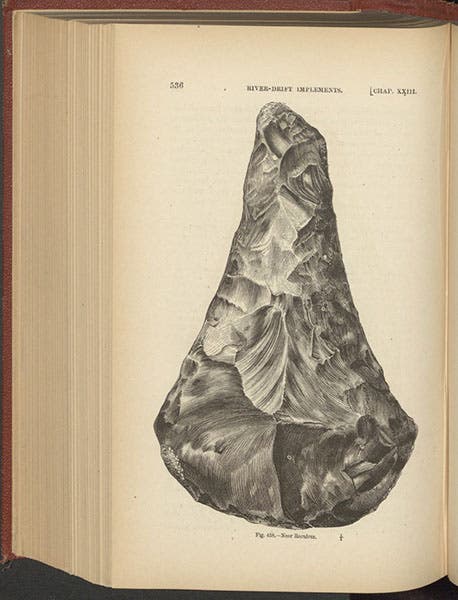

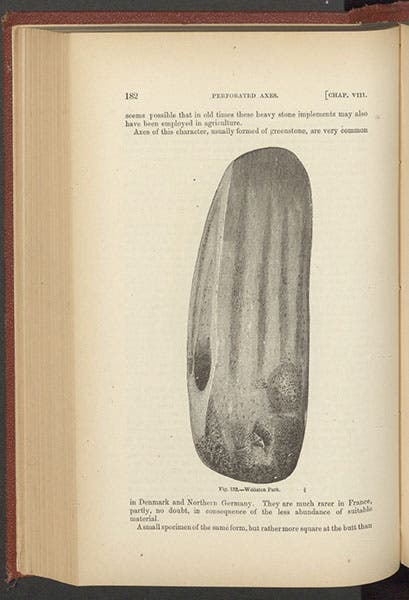

Having presented his conclusions about the tools of Abbeville and Amiens, Evans immediately set out to demonstrate that France did not have a corner on prehistoric stone tools. He sent Prestwich to see the stone tools found at Hoxne in 1797 by John Frere, which were the first British stone tools used as evidence in an argument for human antiquity, by Frere himself, even though no one paid him any attention until he was rediscovered by Evans and Prestwich. Evans collected reports of other ancient British stone tools, including the oldest known, the Gray's Inn Lane hand-axe, found by John Conyers in London in 1679 (third image, above), although Conyers thought it was Roman. Evans pursued this interest through the 1860s, and in 1872, he published The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain, essentially an illustrated catalog of stone tools found in Great Britain. The Library does not own this book, but I do, and most of the illustrations for this post, other than the Amiens flint and the portrait, come from this work. There is a hand-axe from Biddenham, Bedford, found in 1861 (fifth image, above); a rounded hand-axe found by Thomas Leech at Reculver, Kent, in 1860 (sixth image, just above), and a hand-axe found by Evans himself at Reculver in 1861 (seventh image, just below). He even included a few polished tools from a later epoch, which we recognize as Neolithic; they were called by archaeologists "Celts", after their supposed makers (last image).

Flint hand-axe from Reculver, Kent, found by Evans, 1861, wood-engraving, in John Evans, The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain, 1872 (author’s copy)

Polished celt from Wollaton Park, Nottingham, wood-engraving, in John Evans, The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain, 1872 (author’s copy)

Evans lived until 1908 and was the one of the most distinguished archaeologists in England at the time of his death. He had amassed a rich personal collection of books and antiquities; his artifacts were given the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, and his library went to the Bodleian Library, also at Oxford. Evans’ son Arthur John was himself an important archaeologist, excavating the ruins of the palace of Knossos on Crete, beginning in 1900. We wrote a post on Arthur John Evans just this past summer.

The photo-portrait of John Evans (second image) may be found in the Life and Letters of Joseph Prestwich (1899), in the Library's collections.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.